…a story of cloth, currency, and courage in modern Nigeria

In Zaria’s ancient quarter of Kofar Doka, there is a gate painted indigo. Beyond it, the air smells of fermented leaves, wet earth, and something older than both—memory.

This is the home of Rahila Yakubu, a woman who has taken the forgotten craft of indigenous dyeing and spun it into a multi-billion-naira enterprise that touches three continents, revives forgotten skills, and stitches Nigeria into the fabric of global fashion once more.

But Rahila’s story does not begin with millions.

It begins in 2001, when she was just 19, jobless, and watching her father’s old transistor radio cough out the voice of a government minister declaring that Nigeria must “diversify.” She smiled bitterly. The women in her family had been diversifying since independence—with thread, needles, gourds, firewood, and hope.

Read also:¬ÝA look into Nigeria‚Äôs Adire (Tie and Dye) industry, BusinessDay ‚ÄúGo Local‚Äù podcast

The First Vat: One Calabash, Two Hands, ₦4,800

Rahila’s journey into dyeing began with a borrowed calabash and ₦4,800—her life savings. It bought her a sack of indigo leaves, harvested in Kagarko, and a few yards of raw cotton. She built her first fermentation pit using repurposed clay from a nearby construction site. Her hands were blistered for weeks.

She sold her first dyed cloth—a deep, stormy blue adire eleko—for ₦1,200 at the Zaria railway market.

She sold eight more that week. Then 16. Then 52.

By the Numbers: Growth Rooted in Soil and Culture

In 2025, Rahila Yakubu’s name hums through the Nigerian entrepreneurial landscape like a song woven from silk and soil. Her business now generates an impressive ₦2.8 billion in annual revenue, with nearly ₦980 million of that coming from foreign exchange earned through exports. It’s not just about money—it’s about movement. Her operations ripple across 14 countries, from Dakar to Dubai, Accra to Antwerp, and Nairobi to New York.

Behind these numbers is a growing workforce that reflects the depth of her impact. Rahila directly employs 176 full-time staff in her Kaduna and Abuja facilities—most of them women, many of them breadwinners. Add to that another 412 part-time artisans: dyers, weavers, stitchers, spinners. These are the hands that turn cotton into culture.

Her farms span 214 hectares across Bauchi and Niger states, producing cotton that is processed locally and then spun into elegant, export-ready fabrics. Her looms hum at a pace of 3,000 to 4,200 yards of fabric per month, a productivity level that has doubled since 2021. Every yard tells a story—some dyed in indigo, others in kantu leaf green, and all bearing the signature of resilience.

But perhaps Rahila’s greatest achievement lies in her commitment to nurturing others. Since founding her vocational program in 2017, she has trained more than 1,900 young Nigerians, giving them more than just skills—she offers them the chance to dream in colour and sew their way into dignity. Many of her graduates now run independent tailoring outfits or supply design houses across the continent.

In a country often boxed in by pessimism, Rahila’s enterprise stands as proof that one woman’s clarity of purpose can thread together tradition, empowerment, and growth—and stitch the fabric of a stronger Nigeria.

And this is what makes her brand, Rahila Blues, rare. It’s not just a fashion house. It is a vertically integrated cultural industry:

- Cotton grown in Funtua, Katsina

- Ginned in Kano

- Spun in Aba, Abia State

- Dyed and designed in Zaria, Kaduna

- Packaged and exported from Lagos

This full-cycle domestic chain creates 512 indirect jobs and keeps over ₦1.3 billion within Nigeria’s economy every year.

When Cloth Becomes a Nation’s Voice

In 2023, Vogue Italia named Rahila one of “The 12 Artisans Redefining Global Fashion.” But more than the accolades, her most poignant victory came when she secured a multi-year contract with MUJI Japan to supply naturally dyed cloth for their heritage series. That deal alone is worth $1.4 million over four years.

But she didn’t get there with Instagram aesthetics or glitzy fashion shows. Rahila got there with a 60% reinvestment strategy, a 14-day natural fermentation process, and an instinct for storytelling. Every cloth comes with a QR code that links the buyer to a short film about the woman who dyed it, the leaf that colored it, and the story it tells.

“When a woman in Tokyo wears my scarf,” Rahila says, “she wears the story of Aisha from Kankara, whose hands danced the pattern into being.”

Read also:¬ÝTop 100 women in African fashion

Why This Story Matters

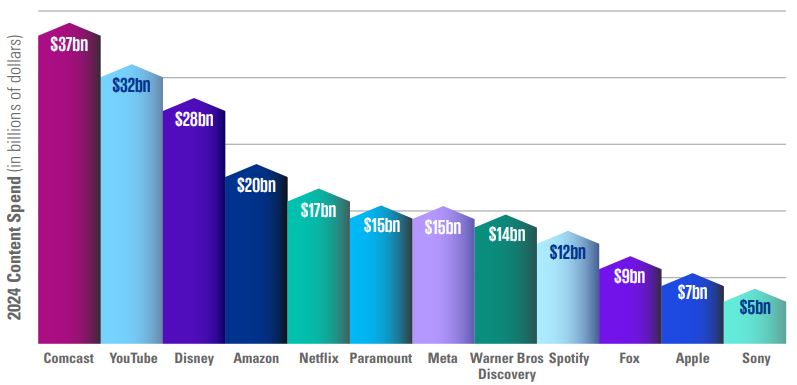

Nigeria’s creative economy contributes about $7 billion to GDP annually, yet the textile sector remains underpowered, with over $2.1 billion in lost import substitution opportunities. In this vacuum, entrepreneurs like Rahila are quietly filling the gap.

If just 200 Rahilas received access to working capital, stable electricity, and direct trade support, Nigeria could triple its non-oil FX earnings from the creative-industrial sector by 2028.

Rahila’s model is export-ready. Carbon-light. Gender-inclusive. Locally sourced. And—most importantly—resistant to naira volatility because it earns in dollars and euros.

She is what industrial policy should look like in practice, not paper.

The Chant of the Women

Every Wednesday, Rahila’s courtyard comes alive with singing.

The women dyeing cloth chant an old Hausa refrain:

“Ba ruwan shinkafa ke kawo launin riga ba,

sai ruwan zuciya, da sabbin fatan gobe.”

(It is not just water that dyes the cloth,

but the soul, and the hope of tomorrow.)

They do not wear gloves. Their fingers are calloused. Their palms are blue. But their joy is unspoiled. For them, this is not work. This is legacy. This is survival. This is how the naira is built—not only by big policies, but by small hands that refuse to stop creating.

Read also:¬ÝOlabisi Dada, transforming Africa‚Äôs rich natural resources into global skincare solutions

To Investors, Policymakers, and Dreamers

Rahila is not just building a brand.

She is restoring value to the Nigerian name tag.

She is proof that indigenous knowledge, when merged with enterprise, can outperform synthetic strategies.

Her story is not fiction.

It is a blueprint.

And if the Central Bank, state governments, and development finance institutions are paying attention, they will see that sometimes, the most powerful factories are not made of concrete and steel, but of tradition, intention, and cloth.

So the next time you hear of foreign direct investment or naira volatility or economic diversification, remember this:

A woman in Zaria dyed the sky blue—and the world paid for it.