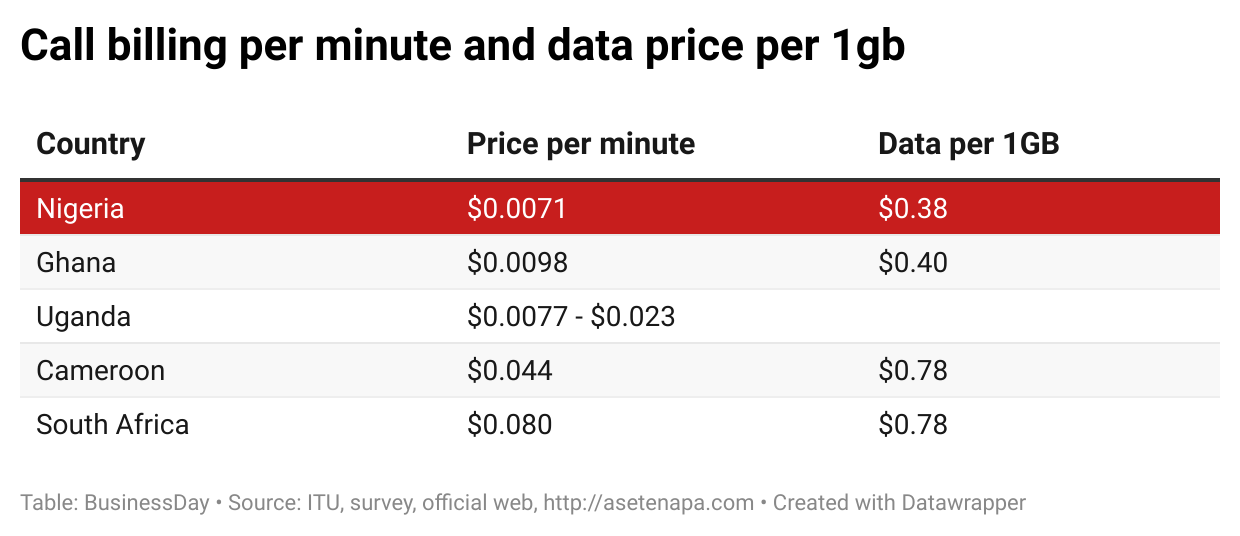

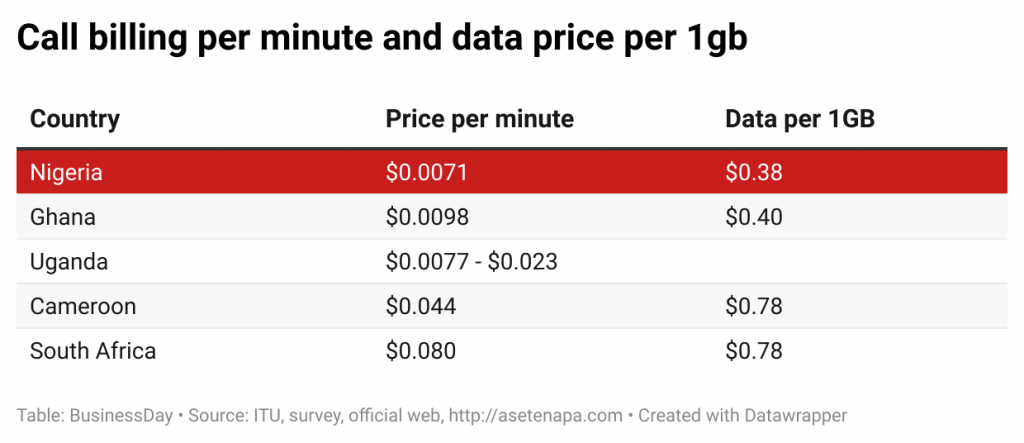

Data from five African countries reveals an interesting disparity: Nigerians pay the least for phone calls. Research by BusinessDay shows that a Ghanaian pays an average of $0.0098 (N16) per minute, while a Ugandan pays between $0.0077 (N11.93) and $0.023 (N34.66) per minute. South Africans pay a staggering $0.080 (N123.57) per minute, Cameroonians $0.044 (N67.81), and Nigerians a modest $0.0071 (N11) per minute.

Furthermore, Nigeria boasts one of the world’s cheapest data rates at $0.38 per 1GB, compared to $0.40 in Ghana and $1.77 in South Africa.

However, comparing prices using exchange rates may exaggerate the cost-of-living differences between these nations, especially as the naira depreciated by about 129 percent from 2023 to 2024.

This depreciation not only strained consumer wallets but also created a challenging business environment for telecom operators, whose operations rely heavily on imports and foreign currency transactions.

If the proposed 40 percent tariff hike is implemented, the average call rate will rise from N11 to N15.4 per minute, while the cost of 1GB of data will increase from an average of $0.38 to $0.53, approximately N827.

However, if a 60 percent hike is adopted, the average cost of phone calls will climb to N18.33 per minute, SMS charges will rise from N4 to N6.67, and the price of a 1GB data bundle will surge from N1,000 to at least N1,667, according to Bosun Tijani, the Minister of Communications, Innovation, and Digital Economy.

How will Nigerian consumers respond to these changes, given their ongoing pursuit of maximising utility while minimising costs?

Consumer behaviour and the theory of Demand

One of the most fascinating topics in economics is the theory of consumer behaviour, specifically the theory of demand. Consumers aim to strike a balance between price and quantity demanded. When the price of a product rises, they often seek cheaper alternatives. Yet, this reaction depends on whether the product in question is elastic or inelastic.

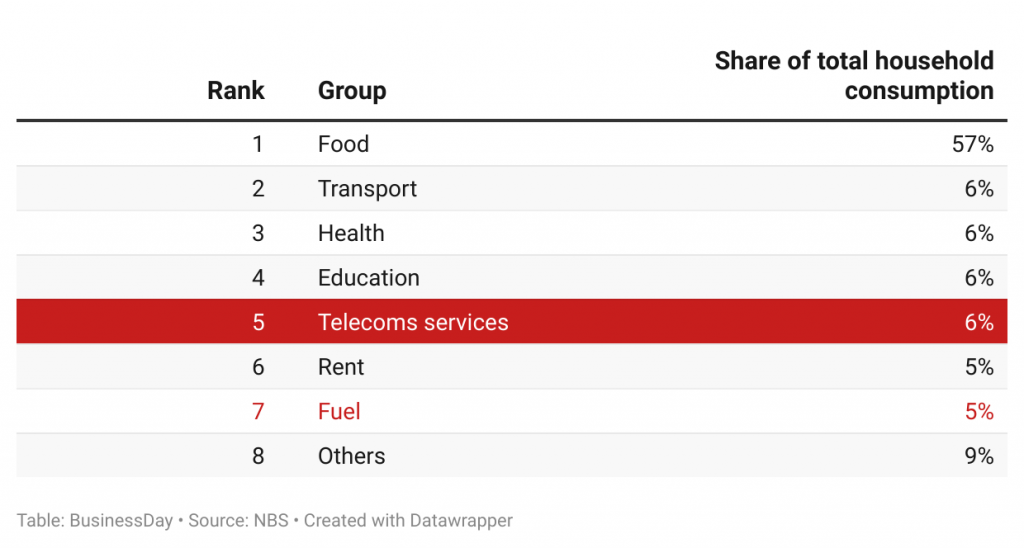

In telecommunications, the demand for SIM cards, recharge cards, and data is relatively inelastic. For example, a 40 percent increase in the price of data may not lead to a proportional reduction in demand, as data accounts for only about 6 percent of household spending. Any decline in demand, if it occurs, is likely to be less than 40 percent.

This stands in stark contrast to elastic goods like food, which make up about 57 percent of household spending. In such cases, a 40 percent price increase could result in a significantly sharper drop in demand.

Historical pricing dynamics in Nigerian Telecoms

The Nigerian telecoms industry has a storied history of pricing evolution. In its early days, phone calls were billed per minute at a rate of N50. Even if your call lasted 50 seconds, you would still be charged for a full minute. The entry of Globacom (GLO) disrupted this model by introducing per-second billing, which was revolutionary at the time. Despite this, early per-second billing rates still translated to about N25 per minute.

Telcos, recognising consumer sensitivity to price, devised innovative tariff plans to attract users. MTN’s “Xtracool” plan, for instance, allowed users to make unlimited free calls between 12:30 a.m. and 4:30 a.m. for as little as N100 in their account balance. This plan became wildly popular among Nigerian youth, who adjusted their schedules to take advantage of the offer. GLO responded with equally competitive offers, such as the “GLO Infinito” plan, which allowed users to call designated numbers at rates as low as N0.01 per second.

Even the procurement of SIM cards was once a luxury. A SIM card that cost about N46,000 in the early 2000s is now practically free, thanks to increased competition and liberalisation in the industry. This intense competition has not only lowered costs but also increased accessibility, making telecom services a vital part of daily life for millions of Nigerians.

Price sensitivity and the impact of a hike

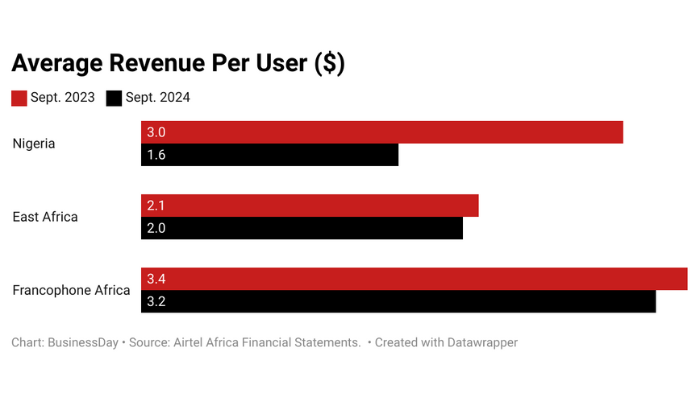

Despite the industry’s history of competitiveness, a tariff hike is inevitable due to the economic realities facing telcos. The last upward price review occurred 12 years ago, in 2012/2013, when Nigeria had approximately 113 million subscribers. By 2014, this number had grown by 9.04% to 127 million. However, subscriber growth does not necessarily translate to higher average revenue per user (ARPU), especially in a low-income economy like Nigeria.

Nigerians’ purchasing power is significantly lower than that of their counterparts in South Africa. This means that while Nigeria’s subscriber base is larger, the ARPU is much smaller.

The proposed price hike may further marginalise those at the lower end of the economic spectrum, potentially limiting their access to affordable data and call services. Yet, it’s worth noting that many Nigerians are unaware of the actual per-second or per-minute charges they incur, focusing instead on overall affordability.

Competition and liberalisation are not the same across sectors

The Nigerian telecoms industry has long been cited as a case study of how liberalisation and competition can drive down prices. However, this principle may not apply universally across other sectors. Competition may force down telecommunications products—like SIM cards, recharge cards, and data. This is not the case for other goods, such as food items, petrol etc., where liberalisation and competition may not always translate to a decrease in prices.

Economic implications

Telecom services rank among the top five items consumed by households, according to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Data, in particular, plays a pivotal role in Nigeria’s creative economy, including financial services. It also supports student learning and skills acquisition. However, higher data costs could widen the existing skills gap, especially among low-income consumers.

This situation presents an opportunity for states to strengthen their economies. By addressing broader economic challenges such as job creation and income inequality, governments can help cushion the impact of such price hikes on vulnerable populations. Additionally, telecom companies must continue to innovate by offering flexible and competitive plans that cater to diverse consumer needs.

The Nigerian telecom industry has come a long way—from N46,000 SIM cards and N50-per-minute calls to today’s more affordable options. While challenges like currency depreciation and an unfavourable business environment persist, they underscore the importance of resilience and adaptability for both the industry and its consumers.