Social media has been flooded with comparisons between Nigeria and Ghana, with many posts concluding that one country is more expensive than the other based on simple currency conversions to compare prices. The logic goes like this: if a pack of noodles sells for 12.5 cedis in Ghana and the exchange rate converts that into N1,677.11, while the same noodles sell for N537.5 in Nigeria, then Ghanaians must be worse off.

It sounds straightforward, but the truth is that economists abandoned this type of analysis years ago. Exchange rates are useful for international trade and investment flows, but they are a poor guide to measuring people’s day-to-day welfare. Instead, economists and other international institutions prefer to use a concept called purchasing power parity (PPP). Unlike the exchange rate, which tells you how much one currency trades for another in global markets, PPP tells you how much a unit of currency can buy at home relative to another country. It is, in effect, a way of measuring living standards through the lens of domestic purchasing power.

How it works

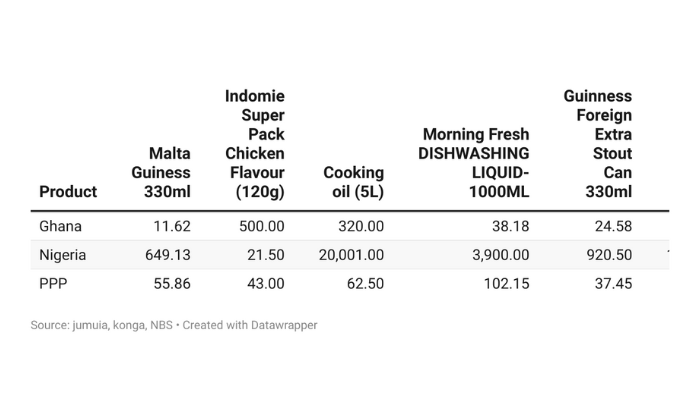

This is how it works. Take the case of Indomie noodles. In Nigeria, a pack of Super Chicken flavour costs about N537.50. In Ghana, the same pack sells for 12.5 cedis. If you rely on the exchange rate, Ghanaians pay N1,677.11, higher than the Nigerian price. But once adjusted for PPP, the Ghanaian price is N43, which means Ghanaians actually get noodles much cheaper than Nigerians do. In other words, ₵12.5 in Ghana buys the same value of noodles as N43 would in Nigeria, showing that Ghanaians actually spend far less in real terms than Nigerians.

The distortion is even bigger with cooking oil. A 5-litre bottle in Ghana costs 320 cedis. Convert that directly and you get about N42,954.37, as against the Nigerian price of N20,001. But the PPP adjustment shows the Ghanaian equivalent is around N62.50, revealing a huge gap in favour of Ghanaians.

Read also: Nigeria’s trade rebounds as currency stabilises

Everyday beverages tell a similar story. A bottle of Malta Guinness at 11.62 cedis equals N1,559.78 by exchange rate, but PPP brings it down to N55.86. Guinness Foreign Extra Stout at 24.58 cedis converts to N3,299.43 at the market rate, but is just N37.44 in PPP terms.

In other words, while exchange rates make Ghana look unaffordable, PPP shows the opposite: Ghanaians are actually paying less for many essential goods compared to Nigerians.

So why is there such a big difference between exchange rates and PPP? The answer lies in what exchange rates measure. A currency’s external value is shaped by factors like balance of payments, foreign reserves, capital flows, and investor sentiment. In Nigeria, for example, years of dollar shortages, high import dependence, and years of foreign exchange volatility have weakened the naira. That weakness inflates Ghanaian prices when converted into naira, even though the goods are not nearly that expensive for Ghanaians themselves.

PPP, on the other hand, strips out these distortions. It measures how much local people can buy with their currency relative to people in another country. That is why international organisations such as the IMF and World Bank often use PPP-based GDP figures when comparing living standards.

Of course, PPP is not perfect. It cannot capture differences in product quality, availability, or consumer preferences. Nor does it fully reflect issues like inflation, volatility or wage disparities. But it is a far better tool than exchange rates for making welfare comparisons.

For Nigerians and Ghanaians debating whose economy is doing better, the lesson is clear. Exchange rates are a poor proxy for living standards. They exaggerate hardships in one country and understate them in another. Welfare comparisons need to go beyond currency conversions and look at purchasing power, productivity, wages, and access to public services.

As the table of common goods shows, when adjusted for PPP, Ghanaians are paying far less than Nigerians for many essentials. That doesn’t mean Ghana has solved all its economic problems; inflation, debt, and unemployment remain pressing issues. But it does mean that the social media debates that rely on currency exchange rates are missing the real picture.

In short, if you want to know how people live, don’t ask the exchange rate. Ask how far their money goes at home.