Venezuela has two presidents but none of them has a handle on an economy in tatters. Three million of its 31 million people have fled the country. Inflation has risen over 1,000,000 percent, which means the price of bread will double when you return to buy again by evening. Now there is a fight about aid. These are consequences of a sham election, something Nigeria should be wary of.

Nigeria has Africa’s biggest oil reserves and produced 1.792 million barrels a day in January, the most of any African country, according to OPEC figures. But these will offer little security if the elections turn violent. Again, Venezuela serves as a fitting lesson.

Venezuela has the worlds’ highest proven oil reserves totalling 297 billion barrels and is a leading exporter of petroleum products. Today, bogged by sanctions from the United States, which stem in part from a sham election, the country’s production has fallen from 3.4 mb/d to about 1.3 mb/d.

“The imposition of sanctions by the United States against Venezuela’s state oil company Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) is another reminder of the huge importance for oil of political events,” International Energy Agency, a Paris-based energy think tank, said in its market report released February 13.

Presidential elections were held in Venezuela on May 20, 2018, with incumbent Nicolás Maduro re-elected for a second six-year term. But several NGOs, international observers and countries like Australia and the United States and opposition candidates rejected the electoral process.

Maduro was sworn in as president anyway on January 10, 2019 and, days later, Albania, Canada, Iceland, Israel, Kosovo, the United States, and a number of Latin American countries recognised National Assembly Speaker Juan Guaidó as the legitimate president after the start of the 2019 Venezuelan presidential crisis.

However, limiting Venezuela’s crisis to poor election outcomes takes a narrow view of the challenge.

Garth Friesen, CEO at III Capital Management, a hedge fund with approximately $4.5 billion assets under management, told Forbes that the story of how Venezuela went from relative stability to hyperinflation includes tales of corruption, social unrest, self-serving politics, capital controls, price-fixing and a global commodity bust.

The problem is that similar conditions are already at play in Nigeria. Transparency International raised questions about Nigeria’s war against corruption when it released its latest ranking which indicates that Nigeria has not moved a needle on the fight. The EFCC says it has secured hundreds of convictions, but it has found it difficult to shake off the perception that the fight is targeted at opposition members.

Farmer-herder conflicts which have decreased in recent times are threats to the nation’s food security breeding social unrest. The spectre of violence from Boko Haram hangs about the north and insurgency in the Niger Delta is a present concern.

Nigeria’s economy is held in the balance as the Central Bank uses currency controls to keep the naira stable. To keep the price of fuel stable, the government pays over N1 trillion yearly in subsidies and the fear of a commodity bust has seen OPEC impose supply cap on production by members.

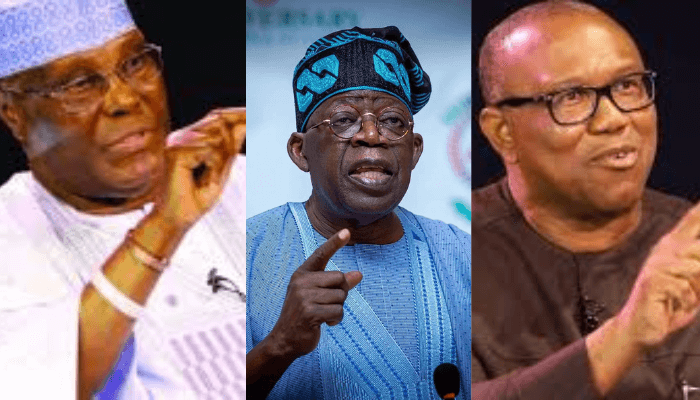

Nigerians will go to the polls this Saturday to elect a president with the elements that precipitated Venezuela’s crises simmering below the surface. A sham election could spark a flame that may not easily be put out.

“As Venezuela stands today, it’s almost run out of foreign reserves, it has lost access to foreign debt markets, it is out of favour with other governments (except Iran) due to political corruption, its nationalised economy is horribly inefficient, and its people are literally starving in the streets,” said Friesen.

This is why international agencies and foreign governments have been calling for a peaceful conduct of the elections in Nigeria because there is life after elections.

ISAAC ANYAOGU