My first encounter with Ukwa was when I travelled to Anambra State some years ago. That was between 1999 and 2004.

Well, my first impression was that the food was a common culinary delight in Anambra State. It was later I discovered that Enugu State is well and better known for Ukwa than any other State in South-Eastern Nigeria as well as other states of the federation.

As a student at that time, I saw many South Easterners relishing this protein enriched grain which I mistakenly viewed as a ‘messy delicacy’.

At first, I was not comfortable with the way the delicacy was being packaged, especially because I found it too ‘messy’ and ‘mashy’ for my liking. But guess what, a friend managed to convince me to taste the food. Initially, I was reluctant, not knowing how the food would taste, especially because, at that time, I observed that the food was too plain and blank. I felt it was not mixed with enough palm oil. In fact, I felt it was not oily enough. But I later tasted the food I usually described as ‘too messy’ and fell in love with it.

A couple of years later, a young man, Nduka Nwaiziogoede, a Computer Science graduate, who worked me at the UnilagFM News Room as a volunteer and intern from the University of Nigeria Nsukka, while discussing with me, decided to package a homemade how -to-cook writeup on Ukwa, this protein-enriched food.

Well, I had to repackage the story in a delicious foodicious way!

In the quiet kitchens of southeastern Nigeria, especially Enugu and Anambra States, every pot of Ukwa often simmers slowly, releasing a pleasant aroma that evokes memory, identity, and belonging. To many, it’s just a meal, but to those who understand its roots, Ukwa represents the enduring story of South Eastern Nigerian culinary culture, resilience, hospitality, and tradition.

Ukwa is the Igbo name for African breadfruit (Treculia africana), a nutritious food popular in Nigeria that is often prepared as a porridge with ingredients like palm oil, bitter leaf, and dry fish. It is considered a cultural delicacy and is traditionally served at home, and at virtually all special occasions in the East.

Common preparations of Ukwa include porridge with various ingredients, simply boiled with seasoning, fried or roasted as a snack, and combined with sweet corn for varied texture and flavour. Ukwa is can also be described as an edible traditional fruit that belongs to the Moraceae family and closely related to other exotic fruits like breadnut, jackfruit, figs, and mulberries, amongst others.

In Igbo households, Ukwa na miri oku (Ukwa in hot water or porridge form) is a meal of prestige and hospitality, often reserved for honoured guests. The preparation process, from harvesting to soaking, boiling, and seasoning is a ritual of patience, craftsmanship, and tradition, passed down through countless generations. It is also tied to identity and communal sharing, and often served at village meetings, weddings, and festivals symbolizing unity and abundance, memory, identity, and the endurance.

As global conversations about food heritage and sustainability grow louder, Ukwa stands as one of Nigeria’s most culturally and nutritionally significant indigenous foods deserving a rightful place on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) list.

This is because the meal beyond the plate. Ukwa holds deep cultural symbolism. It is traditionally served to honour guests, mark festive gatherings, or celebrate milestones. The dish blends African breadfruit seeds with palm oil, pepper, and sometimes ugba (oil bean), resulting in a hearty and satisfying delicacy.

The preparation is a ritual in itself, from the tedious process of soaking and boiling to the careful balance of ingredients. Mothers and grandmothers have passed down these techniques for generations, teaching patience, respect, and gratitude through food.

Beyond its cultural depth, Ukwa is a nutritional powerhouse. Studies show that the African breadfruit is rich in plant-based protein, dietary fibre, and essential minerals. It provides an indigenous, affordable source of nutrition for a nation seeking alternatives to imported staples. Infact, the regular consumption of Ukwa can help to inhibit the absorption of glucose from and even help in controlling diabetes. This is because it contains compounds, which are needed by the pancreas for producing insulin in the body. Ukwa has good sources of energy, along with essential vitamins and minerals such as magnesium, potassium, zinc, iron, and calcium. It is heart-healthy and helps in regulating blood sugar.

Ukwa is both a protein and carbohydrate source, though it is higher in carbohydrates (about 30-40%) than protein (about 15-20%). It is a nutritious food that is rich in both macronutrients, as well as healthy fats, and vitamins (like B-complex and C). Its seeds contain amino acids comparable to soybeans, making it a powerful alternative to imported protein sources.

Looking at its tree, the African breadfruit tree, is also a model of climate resilience, requiring minimal maintenance, enriching soil fertility, and offering shade and sustenance to rural communities. The African breadfruit tree contributes to agroforestry, biodiversity, and soil fertility, requiring minimal inputs and thriving in tropical climates as a sustainable crop for both food security and climate resilience.

In a world grappling with food insecurity, Ukwa’s revival aligns perfectly with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on hunger, climate action, and sustainable agriculture.

It is pertinent to note that Breadfruit is at its best and peak when it is and ripe and flavourful. When ripe, it will turn yellow and sometimes brownish and often with lots of old sap on it. But most times, the fruit would usually drop from the tree.

Endangered Culinary Knowledge

Modern urban lifestyles and imported fast foods are threatening Ukwa’s cultural relevance. Many young Nigerians, especially in cities, no longer know how to cook or even identify it.

Traditional preparation methods — soaking overnight, boiling with akanwu (potash), and seasoning with ugba, palm oil, and pepper — risk fading away.

Local cultivation is also declining due to aging farmers, deforestation, and the lack of structured preservation initiatives.

This is exactly where UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage framework becomes vital — recognizing not just the dish itself, but the knowledge, oral traditions, and communal practices that keep it alive.

Ukwa meets the key UNESCO ICH criteria because it:

Embodies traditional knowledge and culinary skill unique to Nigeria’s cultural landscape. It fosters community identity and continuity, especially among the Igbo people. It promotes sustainable agriculture and biodiversity. It deserves safeguarding through research, education, and documentation before it disappears from common culinary practice.

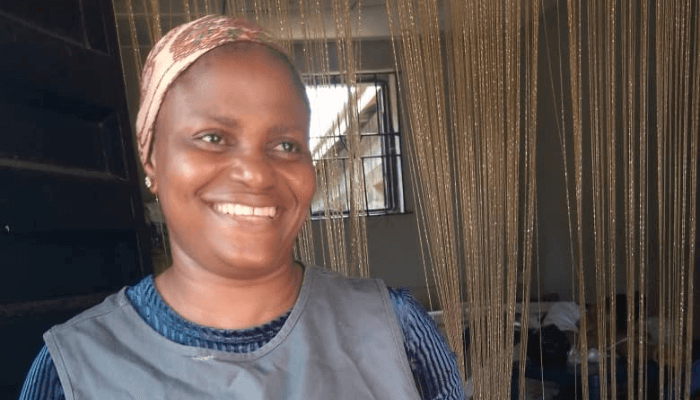

For Ukwa to be added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list, Nigeria’s Ministry of Information, Culture, and National Orientation, in collaboration with cultural researchers and food journalists, would need to document Ukwa’s traditions, preparation techniques, and cultural meanings, engage communities and custodians (especially rural women who prepare Ukwa) and submit a nomination dossier to UNESCO through the National Commission for UNESCO.

In the same vein, Ukwa should be added to Nigeria’s official inventory of intangible cultural elements, alongside dishes like Jollof Rice, Egusi Soup, and Banga amongst others.

A call to action is a call to food journalism and torism, as well as UNESCO advocacy.

Adding Ukwa to the UNESCO ICH list will not only honour Nigerian culinary ingenuity but also secure a sustainable legacy for future generations. “Ukwa is not just what we eat — it’s who we are.”

Let’s visit the kitchen…

Ingredients

Recipe for 3 servings

• 2 cups of dry or fresh Ukwa.

• 2 cooking spoons palm oil.

• 4 fresh peppers [crushed]

• 4 sizeable dry or smoked fish

• A pinch of potash (akanwu).

• 3 tablespoons ground crayfish.

• Salt and seasoning to taste

• A small bunch of bitter leaves [shredded and washed]

Method

• If you’re using dry ukwa, soak it overnight or for a long period of time until it becomes softer, but if it’s fresh ukwa, don’t bother to soak at all.

• Wash the ukwa thoroughly to avoid sand and stones, set on fire and cover to boil until tender.

• Clean the fish, soak in saltwater and wash, breaking the fish into tiny bits and add to the pot.

• Sprinkle the [potash] akawu over the boiling food. This will facilitate the quick and fast softening of the ukwa.

• Add enough water to the pot to cover the ukwa.

• Once it starts boiling and its almost tender, add the crayfish, crushed pepper as well as the salt and seasoning to taste.

• Add the palm oil and continue to cook until the ukwa is very pulpy and tender.

• Uncover the pot, stir with a wooden spoon sprinkle the shredded bitter leaves over the delicacy.

• Cover and simmer for few minutes

• Remove from heat and serve warm.