Even as opportunities slim and documentations and travel expenses continue to go high, some skilled and unskilled Nigerians are still existing in search of better opportunities and conditions.

Although Nigeria is not the only country that has had to struggle with losing its skilled brains to more developed nations, some countriesŌĆÖ strategies hold some lessons on how Nigeria can reverse its brain drain syndrome.

While it is encouraging that Nigerian healthcare professionals are excelling overseas, sadly, their absence is detrimental to the country.

Read also:┬ĀEffiong Bassey: Rethinking mental health in Nigeria┬Ā

If the figure from the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA) is considered, about 2000 medical workers leave the country annually for developed nations, with the majority leaving as a result of low wages and difficult working and living conditions.

To date, Nigerian hospitals are losing the best talents in doctors and nurses, and patients are suffering for it. December 2021 to May 2022 saw no less than 727 Nigerian-trained medical doctors relocated to the UK, and between March 2021 and March 2022, at least 7,256 Nigerian nurses left for the UK.

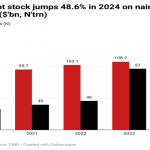

In 2024, the UK granted over 430,000 visas to Nigerian nationals, according to the British High Commissioner, including visas for study and relocation, a December 2024 report showed. In June 2024, the UK issued 432,225 student visas, noted GOV.UK, a 13 percent decrease from the previous year but 61 percent higher than in 2019. In the first half of 2024, the UK processed over 225,000 visas for Nigerian nationals ŌĆō the figure above is for skilled labour, while for the unskilled who use intermediaries, it is not known.

The Nigerian diaspora is overall the best educated, and its members are more than twice as likely to have secured an advanced degree. Nigerians are also more likely than the general American population to work in professional or managerial occupations, according to the US census data.

Taiwan, just like Nigeria, once experienced a classic case of brain drain in the latter half of the 20th century. All efforts by the government to reverse the mass exodus proved abortive as over 100,000 Taiwanese left the country to study abroad.

The country faced the peak of the brain drain in 1979, when only 8 percent of the Taiwanese college graduates who studied abroad returned after completing their studies.

The brain drain led to a great deal of political apprehension in Taiwan, with too many companies chasing too few skilled individuals. Thus, the government began to implement strategies to reverse the syndrome.

With the policies, over 50,000 Taiwanese returned from abroad between 1985 and 1990, with high levels of education and business experience. The expertise they brought fuelled a boom in the domestic high-tech sector.

Reda also:┬ĀHERbernation empowers women to prioritise self-care, mental health, and career growth

According to a study by Harvard Business Review, aided by a growing economy, Taiwan forged business-friendly policies that encouraged entrepreneurs to stay and immigrants to return. Through research, the government of Taiwan observed that most of its top talents were found in Silicon Valley and other hotbeds of technological innovation in the US, so it founded the Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park in 1980.

The park successfully attracted both high-tech firms and returning migrants, and firms in the park employed 102,000 people and generated $28 billion in sales in 2000. Industries were upgraded, and the economy prospered.

The government also promoted tax reductions for industries such as the IT sector. Thus, the opportunities for highly skilled emigrants expanded, and many foreign-trained scientists and engineers came back home.

Another strategy the government used in reversing the brain drain trend was to network with those in the diaspora to offer them attractive incentives. The government established the National Youth Council, which tracks emigrants in a database where Taiwan-based jobs are advertised and incentive packages are offered. The incentives include monetary grants, discounted airfares, subsidised housing in government-owned properties, and subsidised education for those coming with children.

The government also invested in education, the exact kind the economy needed to boost its growth. Unlike many developing nations, the Taiwanese government did not help subsidise advanced education only to lose the gains to developed nations when graduates leave for jobs abroad. Instead, the government invested strongly in universal basic education and vocational programmes lacking in the domestic labour market. Through these programmes, citizens were able to secure jobs, as they had the skills to fill the gaps in the labour market.

Our nation can take example from Taiwan by creating job opportunities with adequate remuneration, providing subsidised training for citizens to improve their employability and also improving the overall quality of life of its citizens.

Read also:┬ĀChallenging mental health stigma in ŌĆ£A Girl, Her God, and Her Mental HealthŌĆØ ŌĆö Asiegbunam

Although the inflow of diaspora remittances is one of the incentives of brain drain that Nigeria benefits from in the short run. However, in the long run, the effect of brain drain is more detrimental to nations, especially when the skilled no longer have any reason to return, as in the case of some Nigerians.

Though Taiwan holds lessons for Nigeria, the current state of insecurity in the country will continue to scare potential investors and also push its citizens out of the country in search of greener and safer pastures. So, the earlier a deliberate policy is implemented with the political will for it to succeed, the better for our beloved nation.

As the adage goes, a stitch in time saves nine.