Nigeria is a country of constant activity, but its economy appears sluggish, remaining outside the top fifty globally. The country has experienced periods of steady growth, and its people work hard, but that effort isn’t translating into real progress for most households. Without a larger pool of decent, higher-paying jobs, hard work alone isn’t enough to lift Nigerians out of poverty.

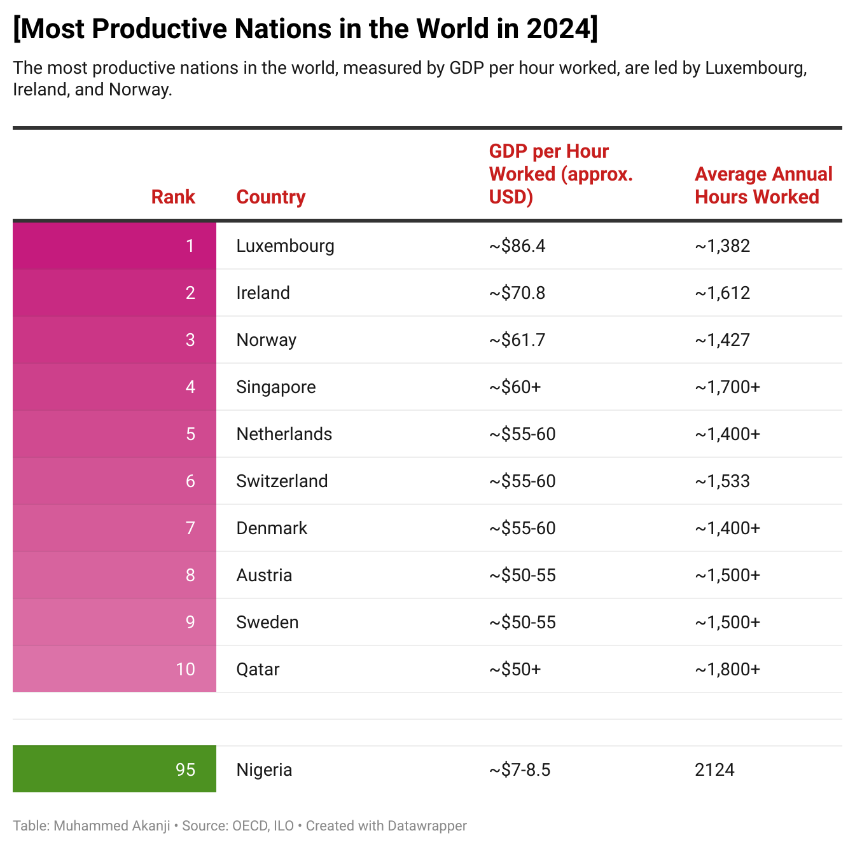

From dawn hustlers to midnight side-gig warriors, Nigerians log some of the longest working hours on the continent. At approximately 2,120 hours of work annually, the nation ranked second globally in terms of hardworking people, highlighting the intense work ethic driven by the nation’s economic conditions.

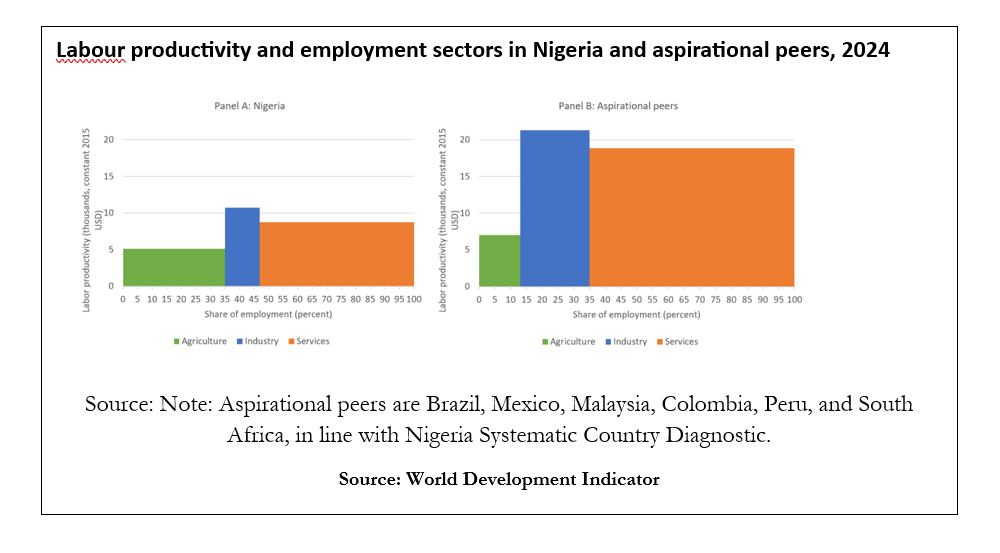

Nevertheless, as the NESG’s Jobs & Productivity Report bluntly shows, all that effort is not turning into national output. Labor productivity has hardly increased over the past decade, remaining stagnant while peer economies quietly surpass us. It’s the irony of a nation running on a treadmill: lots of activity, very little progress.

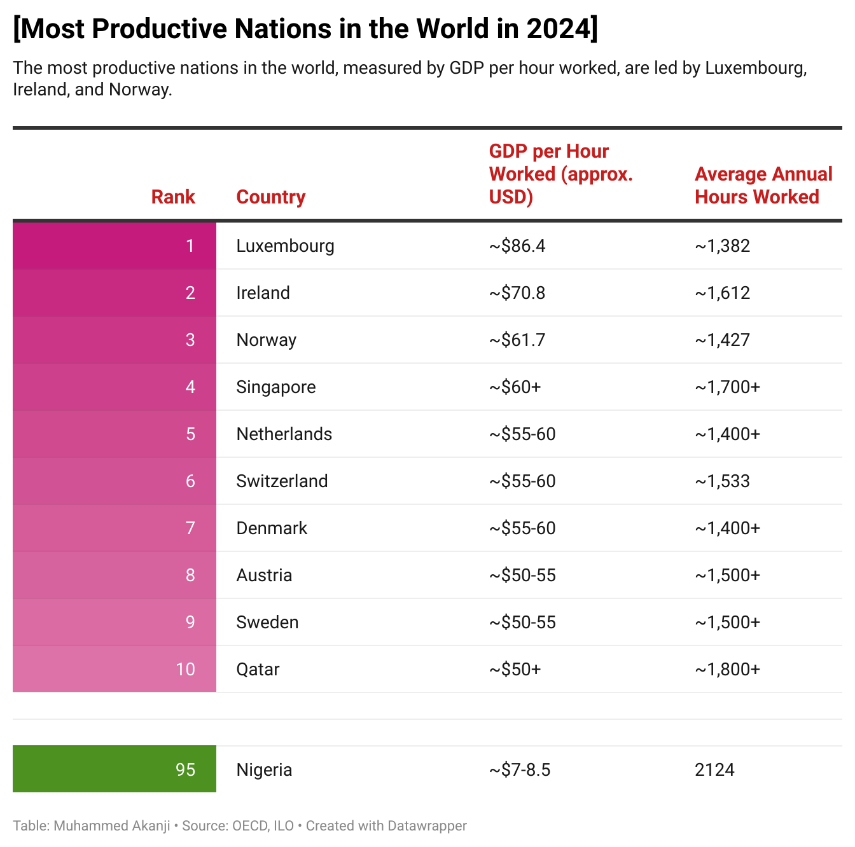

The problem is not a lack of hustle; it is that the hustle is happening in the wrong places. Most Nigerians are trapped in low-productivity informal jobs that keep people afloat but keep the economy stagnant. Extant data shows an economy failing to transform, too few workers shifting into higher-value sectors like manufacturing and modern services, and far too many competing in overcrowded, low-yield activities.

If Nigerians are working harder than ever, why isn’t the economy moving in the same direction?

Why Hustle Fails: An Informal Economy Too Large to Grow

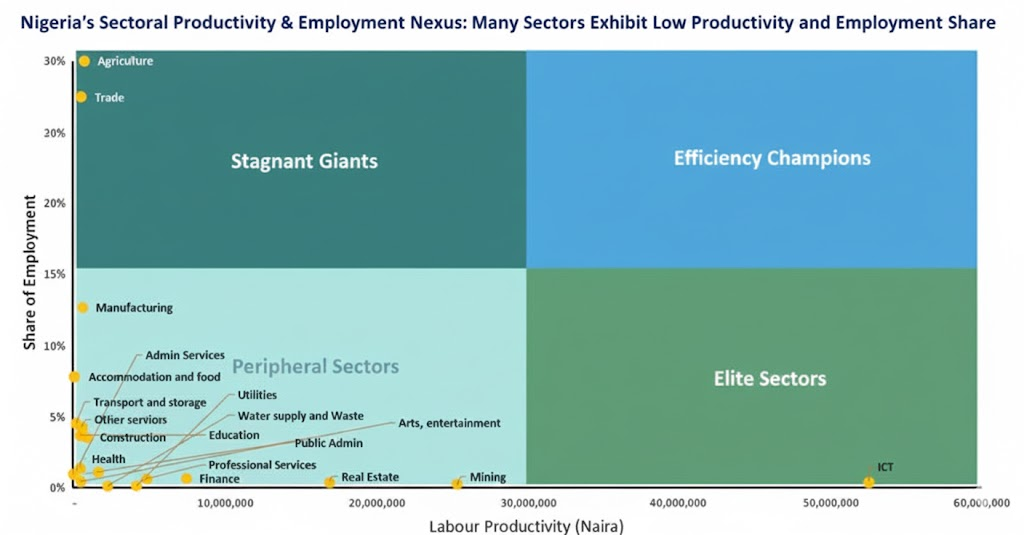

Nigeria’s hustle economy is not failing because people are lazy; it is failing because the labor market is structurally built for low productivity. According to NESG’s analysis, 93% of new jobs created in recent years came from the informal sector, focused on petty trade, subsistence agriculture, street services, and micro-retail hustles. In fact, about 18 states have informal employment, making up nearly 96% of total employment: Kebbi (98%), Abia (97.4%), and others. But this level of informality has significant implications.

These activities keep millions surviving, but keep the economy stagnant. They generate little tax, almost no scalable innovation, and minimal capital formation. Incomes remain low, unpredictable, and vulnerable to shocks.

Meanwhile, the sectors that could boost productivity, manufacturing, ICT, logistics, modern services, and agro-processing, remain too small to absorb Nigeria’s rapidly growing labor force. Manufacturing’s share of employment has barely changed, and formal services are expanding much more slowly than the population. The result is a funnel-shaped economy where most jobs are at the bottom, while most productivity is at the top, with almost no pathway connecting the two.

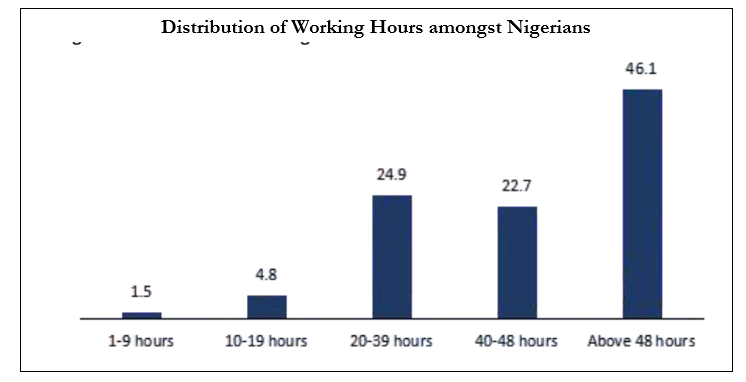

In 2024, NBS posted that a significant share of Nigerian workers in the informal economy worked for longer hours, far above the standard weekly working hours of 40, to make ends meet. In 2023, almost

half (46.1%) of employed persons worked for more than 48 hours per week

This is why the hustle economy feels lively but results in little real change. No country reaches prosperity when its largest employer is survival jobs. Until Nigeria moves labor into higher-value sectors, hustle will stay plentiful and progress will remain rare.

The Structural Drag: Skills Mismatch, Low Capital, Poor Technology

The Structural Drag: Skills Mismatch, Low Capital, Poor Technology

Nigeria’s productivity crisis is not simply a story of low output; it is the outcome of deep structural bottlenecks that choke firm efficiency and undermine national competitiveness. Extant findings show that over 50% of Nigerian firms identify skills gaps as a significant barrier, particularly in technical and mid-level vocational roles. Employers consistently report that graduates lack practical competencies, while the country’s vocational training system remains fragmented, underfunded, and misaligned with industry needs.

Capital constraints amplify this drag. More than 70% of MSMEs rely on personal savings due to limited access to credit, high interest rates, and collateral requirements that shut small firms out of productive investment. Without affordable finance, businesses cannot scale, modernise equipment, or improve worker capabilities.

Technology adoption is equally weak. NESG notes that only a small fraction of firms use advanced machinery or digital tools, leaving most enterprises stuck in low-productivity, manual processes. Poor broadband penetration, unreliable electricity, and costly technology imports further discourage innovation.

Together, these constraints create a narrow productivity trap: low skills hinder technology adoption; limited capital prevents equipment upgrades; weak technology reduces output and wages. Breaking this cycle is key to unlocking inclusive growth.

The Missed Opportunity: Sectors That Could Transform the Economy

Nigeria has powerful, underused economic engines, sectors with the highest potential to create jobs and boost productivity—that are consistently held back by weak policy alignment and structural barriers.

We identify manufacturing, agro-processing, digital services, construction, and logistics as the most transformative. These sectors have some of the highest productivity multipliers in the economy: every job created in manufacturing can generate 3–5 indirect jobs, while agro-processing alone could lift millions out of poverty if supported with storage, power, and market access.

Digital services, one of the fastest-growing segments, can scale rapidly with the right broadband investments and regulatory certainty. Construction and logistics, critical to urbanisation and trade efficiency, remain largely informal and capital-starved. With targeted reforms: stable power, concessional financing, skills pipelines, and efficient ports, these sectors could shift Nigeria from survivalist hustle to productive, inclusive growth.

In summary, although nations such as Kenya and South Africa consistently increase productivity per worker, Nigeria is like the student who studies all night but ends up with the same grade. The problem isn’t a lack of effort; it’s that Nigeria puts in effort, but its economy remains underperforming.