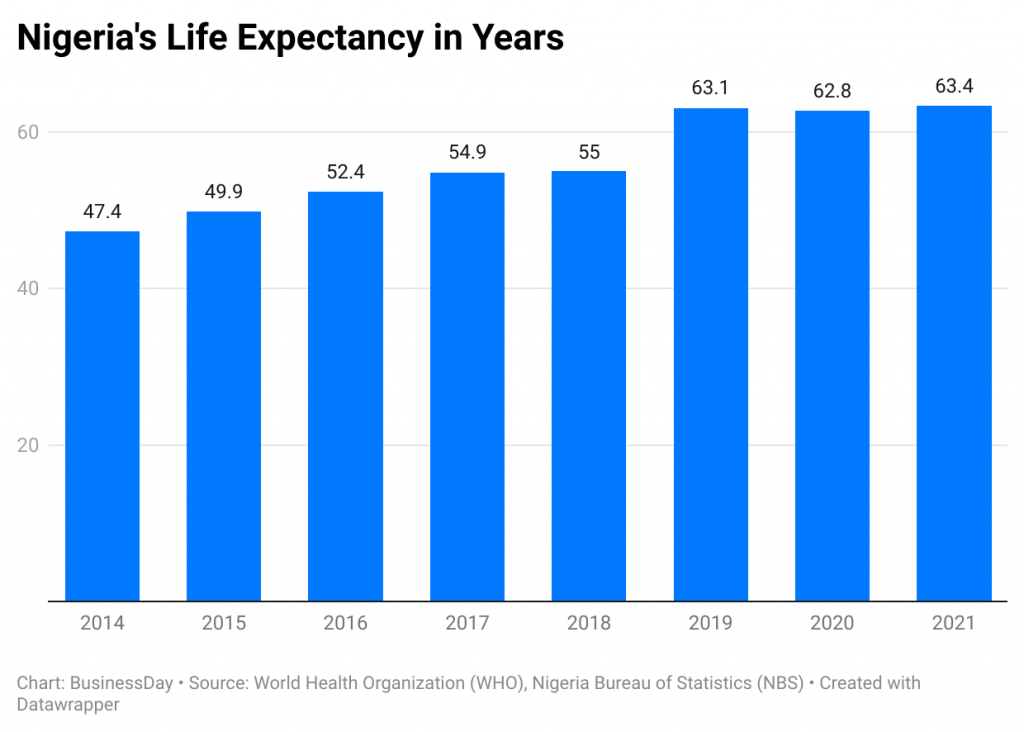

A decade of underinvestment in healthcare and public services has left Nigeria’s life expectancy stagnating at 63 years.

BusinessDay’s World Health Organisation (WHO) data analysis shows that life expectancy grew by 22.6 percent from 51.7 years in 2014 to 63.4 years in 2021 and has stagnated until 2024.

Nigeria allocated a minor portion of its national health budget (N1.14 trillion) to capital health expenditure within this period.

According to the Budget Office of the Federation, the larger portion (N3.39 trillion) was allotted to recurrent expenditures on staff salaries and overhead costs.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, just N417 billion was released from the meagre N1.14 trillion earmarked for capital projects.

Again, only 70 percent (N294 billion) of those releases were utilised, with the budget office tying the funds to construction, rehabilitation, and equipment procurement across federal health institutions over the 10 years.

This funding represents 25.7 percent of a total allocation of N1.14 trillion to capital healthcare projects and, expectedly, the correlation of these expenditures to improved life expectancy is hardly seen, analysts say.

FG spends N1,416 on each Nigerian’s health

Going by capital spending, this implies Nigeria spent N1, 416 per capita for an average population of 207.5 million.

Although the value of the naira has plummeted from N157 per dollar in 2014 to nearly N800 to N850 as of 2023, Nigeria has consistently fallen short of the Abuja Declaration target of allocating and spending at least 15 percent of government expenditure on health.

South Africa achieved and sustained this goal from 2014 to 2020, driving its life expectancy to 65.3 years, according to the WHO African Region Health Expenditure Atlas 2023.

BusinessDay found that about 30 percent of the inadequate funds released for Nigeria’s capital expenditure were returned during the period.

Meanwhile, public health threats such as malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis continue to pose significant risks, particularly to children and pregnant women, further exacerbating the nation’s health challenges.

Akin Osinbogun, a professor of Public Health at the University of Lagos, said Nigeria should ideally aim at a life expectancy of 80 years as obtained in developed countries, even if it takes improving healthcare expenditure and improving the efficiency of resources.

In terms of efficiency, the N294 billion utilised over the last 10 years would only have been sufficient to buy 50 brand-new linear accelerators at the average cost $3.5 million each.

Linear accelerators (LINACs) are advanced medical devices widely used in radiation therapy for cancer treatment.

Nigeria has approximately nine operational LINACs spread across a few treatment centres, primarily in cities like Lagos and Abuja.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) recommends that countries like Nigeria have at least one radiotherapy unit per 1 million people, that is 223 LINACs.

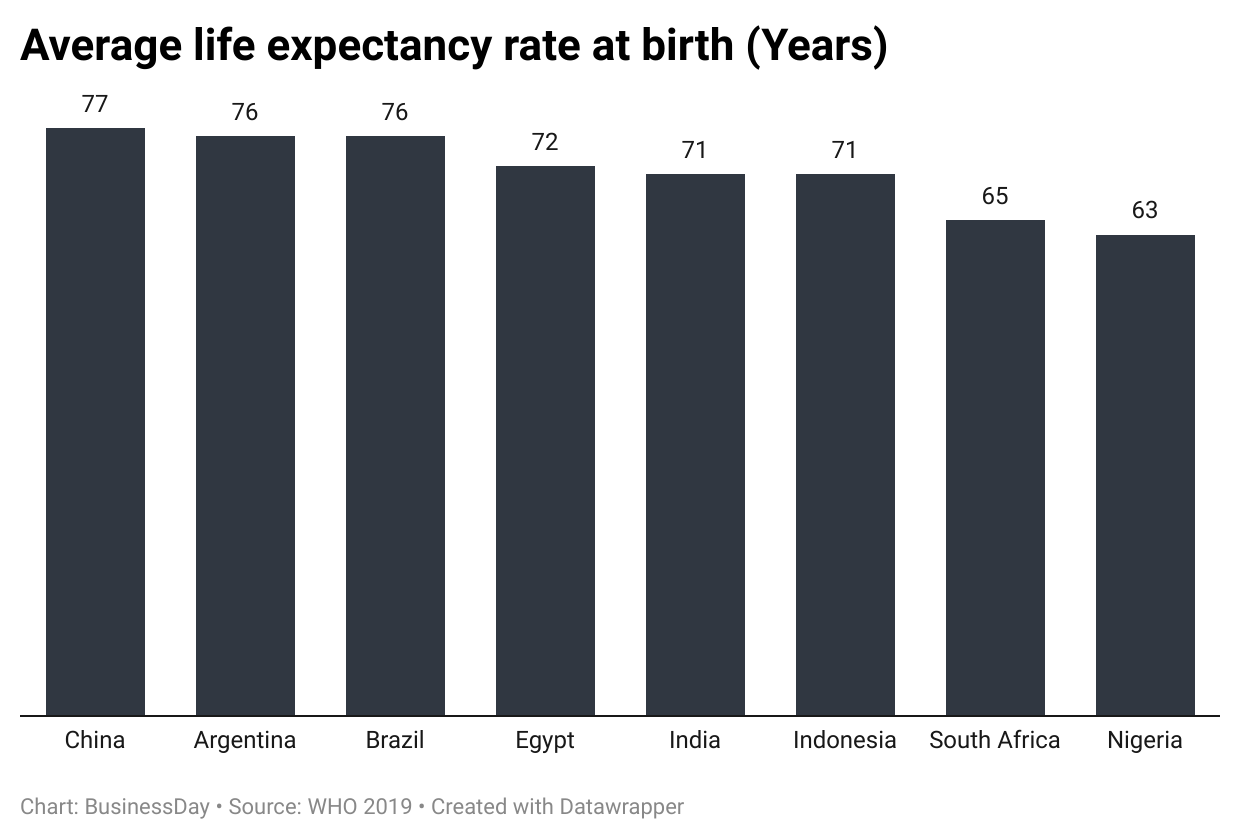

Japan has the highest life expectancy rate at birth with an average of 84 years, followed by 83 in Australia, and 82 in Italy, WHO data shows.

South Africa has an average of 65; Egypt, 72; India, 71; Indonesia, 71; China, 77; Argentina, 76; and Brazil 76.

“If you look at the federal budget for health over the years, it has always been below five percent. If you look at the volume, it appears as if it is increasing but inflation is also increasing, so the actual value has not improved,” Osinbogun told BusinessDay on a phone chat.

“The second point is that you can only spend what you have. While our GDP per capita is about $2,000, the GDP per capita for the United States is about $50,000. So, we have less money than those countries. Even with the less money we have, we allocate a low percentage to health. And we know that the more a country spends on health, the better its health outcomes.”

To achieve such results, Osinbogun said the government must improve the use of resources and invest more in health.

According to a World Bank analysis, Nigeria spends just $15 per capita on healthcare.

The limited health funds that are allocated are primarily directed toward secondary and tertiary care, focusing heavily on curative services in higher-level hospitals.

This spending strategy neglects preventive measures, public health initiatives, and primary healthcare, which are more cost-effective and impactful in improving overall health outcomes.

The report highlights the negative consequences of this skewed approach: it not only depletes resources that could be used for prevention and health promotion but also results in high out-of-pocket expenses for patients.

Health Insurance

Professor Abubakar Bello, former president of the African Organisation for Training and Research in Cancer, said for a population of 223 million people, the mandatory health insurance of the National Health Insurance Authority must be fully operational to raise life expectancy.

“That is an important policy,” he said. “With the way things are in terms of the economy of the country, the government coming in will significantly reduce the difficulties that patients go through as it is today,”

Ele Peter of Tep Foundation, a health advocacy group, called for routine medical check-ups to be institutionalised alongside lifestyle modification efforts to shore up life expectancy in Nigeria.

Citing Singapore’s use of policies to make unhealthy food and car driving more expensive and harder to get, she said individuals must do what they can within limited resources.