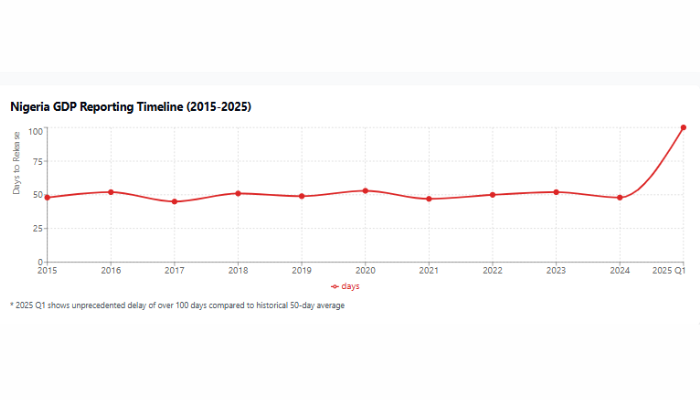

Nigeria’s economic data reporting has entered a troubling phase. The release of the country’s first-quarter 2025 GDP report has been delayed by over 100 days—more than double the historical average of 50 days over the past decade. This unprecedented delay in publishing one of Africa’s most watched economic indicators raises serious questions about institutional capacity, data integrity, and the broader implications for investor confidence in Nigeria’s economic management.

The Scale of the Problem

The release of Nigeria’s first-quarter Gross Domestic Product (GDP) report for 2025 has been delayed by 33 days beyond the country’s historical average, with the total delay now extending well beyond 100 days since the quarter’s end. This represents a significant departure from established patterns. Historically, Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) has maintained a relatively consistent 50-day window between quarter-end and GDP release, placing the country within acceptable international norms for developing economies.

The timing is particularly concerning given Nigeria’s position as Africa’s largest economy and its critical role in regional economic planning. When GDP data is delayed, it creates a ripple effect across monetary policy, fiscal planning, and private sector decision-making that extends far beyond Nigeria’s borders.

The Role of GDP Rebasing in the Delay

The most plausible explanation for the unprecedented Q1 2025 reporting delay lies in the intersection of Nigeria’s ongoing GDP rebasing exercise with quarterly data compilation. The NBS’s decision to rebase GDP using 2019 as the new base year—replacing the current 2010 baseline—creates a complex technical challenge that directly impacts Q1 2025 reporting timelines. The bureau faces the difficult task of simultaneously producing Q1 2025 figures under both the old and new methodologies to ensure continuity and comparability. This dual computation requirement, combined with the need to validate rebased historical series against new sectoral weights and updated consumption patterns, has likely stretched the NBS’s technical capacity beyond normal operational limits. The rebasing process requires extensive recalibration of sector contributions, particularly for Nigeria’s rapidly evolving digital economy, telecommunications, and financial services sectors that have grown significantly since 2010. Rather than releasing potentially inconsistent data under the old methodology only to revise it later, the NBS appears to be prioritizing the accuracy and integrity of the rebased series—a decision that, while methodologically sound, has created the current reporting crisis. This technical bottleneck suggests that the Q1 2025 delay may be a one-time event tied to the rebasing transition, though it highlights the need for better communication about such methodological changes and their impact on reporting schedules.

Institutional Bottlenecks at the NBS

Another possible explanation for the delay lies within the National Bureau of Statistics itself. Like many statistical agencies across sub-Saharan Africa, the NBS faces chronic underfunding and capacity constraints. Budgetary allocations to statistics and data agencies typically receive low priority in government spending, directly affecting the bureau’s ability to conduct comprehensive fieldwork, process complex datasets, and maintain validation timelines. Staff attrition presents another critical challenge. The loss of technical experts, recruitment delays, and institutional restructuring can significantly slow down data processing and report generation. Nigeria’s broader brain drain phenomenon, where skilled professionals migrate to higher-paying opportunities abroad, likely affects the NBS’s ability to retain experienced statisticians and economists capable of managing sophisticated GDP calculations.

The bureau’s operational challenges are compounded by the sheer complexity of tracking Nigeria’s diverse economy. With over 200 million people and an economy spanning from traditional agriculture to emerging fintech sectors, capturing comprehensive economic activity requires substantial resources and expertise that may be stretched thin.

Data Collection Complexities

Nigeria’s economy presents unique data collection challenges that may be contributing to the delay. The country is currently undertaking significant methodological adjustments that could slow standard GDP computation processes. Nigeria plans to rebase its gross domestic product and inflation data by the end of the month to capture changes in certain sectors of the economy and to reflect current consumption patterns, with the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) set to rebase Nigeria’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) this year, using 2019 as the new base year instead of 2010. This rebasing exercise, while necessary for accuracy, adds complexity to current reporting. The NBS must simultaneously maintain consistency with historical data while incorporating new methodological approaches and updated sectoral weights. The process requires careful validation to ensure that the rebased figures accurately reflect Nigeria’s evolving economic structure, particularly the growing importance of services and digital sectors.

Post-census adjustments further complicate the picture. With Nigeria’s population and business base continuously evolving, efforts to realign GDP base assumptions or weights naturally extend processing times. The informal sector, which comprises a significant portion of Nigeria’s economy, presents particular challenges in data collection and validation. Sectoral data gaps also contribute to delays. Gathering timely and comprehensive information from key sectors—especially informal commerce, smallholder agriculture, and rapidly growing services—requires coordination across multiple government agencies and private sector partners. Any breakdown in these data flows can cascade into significant reporting delays.

Political and Strategic Considerations

The delay may also reflect more sensitive political dynamics. The Q1 2025 GDP report could contain politically or economically sensitive information that requires careful handling at higher levels of government approval. If the data reveals economic stagnation, contraction, or evidence of policy failures, there may be reluctance to release figures that could undermine government credibility or complicate ongoing policy initiatives. These speculations are as a result of the delay in releasing the results.

The timing coincides with critical periods in Nigeria’s fiscal calendar. Poor GDP performance could complicate Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) preparations and mid-year budget reviews. Government officials may be seeking additional time to prepare appropriate policy responses or communication strategies before releasing potentially disappointing economic data. This political dimension reflects a broader challenge across developing economies, where economic data releases can become entangled with political considerations. However, such delays ultimately undermine the credibility of economic institutions and can create more severe long-term damage to investor confidence than the release of unfavorable but transparent data.

Methodological and Technical Challenges

The NBS may be using this extended period to implement significant methodological improvements. Modern economies require sophisticated approaches to capture emerging sectors, particularly digital services, fintech, and e-commerce activities that have grown rapidly in Nigeria over recent years. The bureau might be revising its estimation models to better reflect these sectors’ contributions to overall economic output. International benchmarking presents another possibility. The NBS could be aligning its methodologies with international best practices, potentially preparing for comprehensive GDP rebasing that requires extensive validation and cross-checking. Such exercises, while beneficial for long-term data quality, inevitably extend processing times in the short term.

The integration of new data sources, including digital transaction data, mobile money flows, and e-commerce statistics, requires developing new analytical frameworks and validation procedures. These technical improvements, while necessary for accuracy, can significantly extend the time required for GDP compilation.

Economic and Market Implications

The delay carries serious implications for Nigeria’s economic ecosystem. Investor confidence suffers when basic economic indicators are unavailable or delayed. International investors, portfolio managers, and development finance institutions rely on timely GDP data to make informed decisions about Nigeria’s economic trajectory. Extended delays signal institutional weakness and raise questions about data reliability. Monetary policy formulation becomes more challenging without current GDP data. The Central Bank of Nigeria’s Monetary Policy Committee requires accurate, timely economic indicators to make informed decisions about interest rates, inflation targeting, and currency policy. Operating with outdated economic data increases the risk of policy mistakes that could destabilize the economy.

Fiscal planning also suffers. Government agencies, state governments, and development partners need current GDP data to assess tax revenue potentials, plan infrastructure investments, and allocate resources effectively. Delays in GDP reporting cascade into delays in budget planning and implementation across multiple levels of government.

Private sector planning becomes more difficult when businesses lack visibility into real sector trends. Companies making investment decisions, banks assessing credit risks, and international firms considering Nigerian market entry all depend on reliable economic data. The absence of timely GDP figures forces these actors to make decisions based on incomplete information, potentially leading to misallocation of resources.

Regional and International Comparisons

Nigeria’s current delay places it well outside international norms for GDP reporting. Most developed economies release preliminary GDP estimates within 30-45 days of quarter-end, with many achieving 30-day turnarounds. Even among peer developing economies, Nigeria’s 100+ day delay is unusually long. Countries like South Africa, Kenya, and Ghana typically maintain 45-60 day reporting windows, demonstrating that resource constraints need not result in such extended delays. Nigeria’s position as Africa’s largest economy makes these delays particularly damaging to its regional leadership credibility. The delay also affects Nigeria’s standing in international economic assessments. Organizations like the IMF, World Bank, and African Development Bank rely on timely national statistics for their economic analyses and policy recommendations. Extended delays can result in Nigeria being excluded from comparative analyses or receiving lower confidence ratings in international economic assessments.

Recommendations for Immediate Action

The NBS must provide immediate public clarification about the causes of the delay and establish a clear timeline for report release. Transparency about the challenges faced and steps being taken to address them would help maintain stakeholder confidence while the bureau works to resolve underlying issues. Institutional strengthening represents a critical medium-term priority. The federal government should increase budgetary allocations to the NBS, ensuring adequate funding for staff training, technology upgrades, and operational capacity. Investment in statistical capacity should be viewed as essential infrastructure for economic development, not an optional expense.

Data decentralization offers another promising approach. The NBS should expand collaborations with line ministries, private data firms, and technology platforms to improve real-time access to sectoral data. Partnerships with banks, telecommunications companies, and digital payment platforms could provide more timely economic indicators while reducing the burden on traditional data collection methods. Technology adoption should be accelerated. Modern statistical agencies increasingly rely on big data analytics, satellite imagery, and digital transaction monitoring to supplement traditional survey methods. Investing in these capabilities could significantly reduce the time required for GDP compilation while improving accuracy.

Establishing Accountability Mechanisms

Nigeria should introduce performance tracking for key economic data releases as part of its broader governance scorecard. Regular monitoring of statistical agency performance, with clear benchmarks and consequences for delays, would help ensure that data reporting maintains appropriate priority within government operations. Parliamentary oversight could play a valuable role. Regular hearings on statistical agency performance, with clear expectations for data release timelines, would provide external accountability and help identify resource constraints that require legislative attention. International technical assistance should be actively sought. Organizations like the IMF, World Bank, and African Development Bank offer technical support for statistical capacity building. Nigeria should leverage these resources to accelerate institutional improvements and methodological upgrades.

The Path Forward

Nigeria’s GDP reporting crisis represents more than a technical challenge—it reflects broader institutional weaknesses that undermine economic credibility and market confidence. The current delay, while concerning, presents an opportunity to address long-standing capacity constraints and implement reforms that could strengthen Nigeria’s statistical infrastructure for the long term. The stakes extend beyond immediate policy implications. In an increasingly competitive global economy, countries that cannot provide timely, reliable economic data risk marginalization in international investment flows and development partnerships. Nigeria’s position as Africa’s economic leader requires institutional capacity that matches its economic importance.

The resolution of this crisis will require sustained commitment from Nigeria’s leadership, adequate resource allocation, and a recognition that statistical capacity represents critical infrastructure for economic development. The cost of continued delays—in terms of investor confidence, policy effectiveness, and international credibility—far exceeds the investment required to build world-class statistical capabilities. Nigeria’s economic future depends not just on sound policies and robust institutions, but on the ability to measure and communicate economic progress effectively. The current GDP reporting delay serves as a wake-up call for broader institutional reforms that could position Nigeria for more effective economic management in the years ahead.