When President Bola Ahmed Tinubu steps out of his bulletproof Cadillac Escalade and into the soft leather seats of a custom-built Innoson G80 SUV, something more than metal and motion shifts. The motorcade gliding through AbujaŌĆÖs sunlit boulevards is no longer just a symbol of power; it becomes a symbol of possibility. For once, what is Nigerian is also aspirational.

This imagined moment lies at the heart of the newly approved ŌĆ£Renewed Hope Nigeria First PolicyŌĆØ, a sweeping effort to place NigeriaŌĆÖs economic future in Nigerian hands. It prioritises local manufacturers, particularly in strategic sectors like automotive production, and it poses a bold, clear question to every citizen: Would you drive a locally assembled vehicle?

What Nigerians Want ŌĆō and Fear

In Ajah, Lagos, 36-year-old nurse Chika recently bought a Nord A5 sedan. ŌĆ£It felt like a risk,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£But IŌĆÖm tired of used Tokunbo cars breaking down every year. I wanted something fresh and Nigerian.ŌĆØ

Chika is not alone. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) shows that in 2023, Nigerians imported over 400,000 used vehicles, valued at approximately Ōé”1.3 trillion, a staggering sum for a nation seeking to conserve foreign exchange and reduce reliance on imports. And yet, more than 85% of Nigerian vehicles are used and imported, largely due to perceived reliability, lack of awareness, and inconsistent government support for local manufacturers.

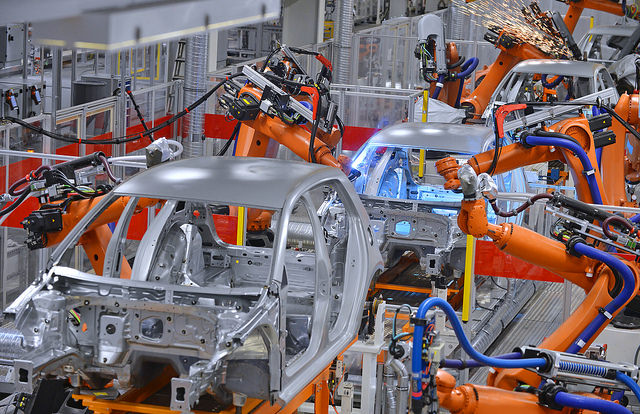

Despite this, interest in locally assembled vehicles is rising. Companies like Innoson Vehicle Manufacturing (IVM) in Nnewi and Nord Automobiles in Lagos are gaining traction. In 2022, Innoson produced nearly 10,000 units, while Nord, barely three years old, has expanded into over 10 states, supplying vehicles to governments and private individuals alike.

Still, many Nigerians remain sceptical. ŌĆ£Are the parts available?ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Will mechanics know how to fix it?ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Will it last as long as a Toyota Corolla?ŌĆØ

What Drives Adoption?

Affordability: A brand-new Innoson Umu sedan starts at about Ōé”8 million, a lower entry point than most imported new vehicles. Local assembly reduces customs duties, shipping costs, and currency-related inflation.

Serviceability: With regional assembly hubs, Innoson and Nord can provide faster access to spare parts and repairs. Unlike imported models that require scarce or expensive parts, local vehicles are designed with NigeriaŌĆÖs terrain, fuel quality, and repair ecosystem in mind.

National Pride: As India did with Tata Motors and South Korea with Hyundai, local vehicle production can be more than economics; it can be identity. It can say, We believe in what we make.

The Lessons of India and South Korea

India launched the Tata Indica in 1998 to much criticism. Detractors called it slow and ugly. But the Indian government, through patronage, import control, and infrastructure support, nurtured Tata Motors. Today, itŌĆÖs a global player, owning Jaguar Land Rover and exporting to dozens of countries.

Similarly, Hyundai began in 1967 in a South Korea ravaged by war. Through consistent government procurement, subsidies, and technology partnerships, Hyundai not only survived but also grew into a titan with plants in the U.S., Europe, and Africa.

In both countries, industrialisation was not left to chance. It was engineered with policy as chassis, commitment as fuel, and innovation as steering.

NigeriaŌĆÖs Window of Opportunity

The Renewed Hope Nigeria First Policy represents NigeriaŌĆÖs industrial inflection point. At its core, the policy directs:

All Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs) to prioritise local goods and services in procurement.

The Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) to enforce compliance and deny waivers unless local alternatives are unavailable.

The development of a national supplier database and disciplinary action for errant procurement officers.

Inclusion of technology transfer and capacity-building clauses in unavoidable foreign contracts.

Backed by Ōé”75 billion for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and manufacturers through the Bank of Industry, and Ōé”50 billion in grants, the policy aims to reduce NigeriaŌĆÖs import bill, strengthen its industrial backbone, and re-anchor government spending in the domestic economy.

If executed with transparency and grit, it could generate over 500,000 direct and indirect jobs within five years, from assembly-line technicians and component manufacturers to rubber tappers in Edo, glassmakers in Kaduna, and logistics firms in Ogun.

Challenges on the Road

Read also:┬ĀInnoson, indigenous car manufacturer, test-runs electric vehicle in Anambra

Yet utopias, like highways, need more than intention.

Infrastructure: Erratic power supply, poor roads, and congested ports drive up manufacturing costs. Without reliable infrastructure, the competitiveness of local cars remains constrained.

Quality Assurance: Nigerian-made cars must meet international safety and performance standards. Anything less erodes trust.

Protection vs. Competition: While support for local industry is crucial, excessive protectionism can inflate prices and lead to complacency. The balance must be carefully struck.

The Power of Symbolism

Imagine this:

The President arrives at the National Assembly in an Innoson SUV. His ministers follow suit. Across Abuja and Lagos, government convoys now feature Nord sedans. In Nnewi, a young boy watches this on TV and says, ŌĆ£I want to be a car engineer.ŌĆØ In Maiduguri, a mechanic trains on electric Innosons. Across Nigeria, belief begins to build.

This is not mere symbolism. It is state signalling, a crucial economic tool. When the state buys local, it validates quality, encourages investment, and builds market confidence.

In countries like Malaysia and Indonesia, the success of national brands like Proton and Pindad was catalysed by government-first adoption, followed by public embrace.

A Car Is More Than a Car

In truth, a locally assembled car is more than a car.

It is a job in Aba, where seat fabrics are sewn.

It is foreign exchange saved in Apapa.

It is a girl in Kano learning automotive coding.

It is a young man in Nasarawa designing the dashboard of tomorrow.

It is an economic transformation tucked neatly under the hood.

So, Would You Drive One?

The answer depends on whether this policy becomes a reality or remains rhetoric. It depends on whether citizens, institutions, and leaders all take the first drive.

Chika in Ajah already did.

Maybe you will too.

And if you hesitate, remember:

Tata was once mocked.

Hyundai was once doubted.

Now, they move the world.

Nigeria can build cars.

But more than that, Nigeria can build belief.