..Funding, regulations, ŌĆśforced marriagesŌĆÖ undermine confidence in new licences

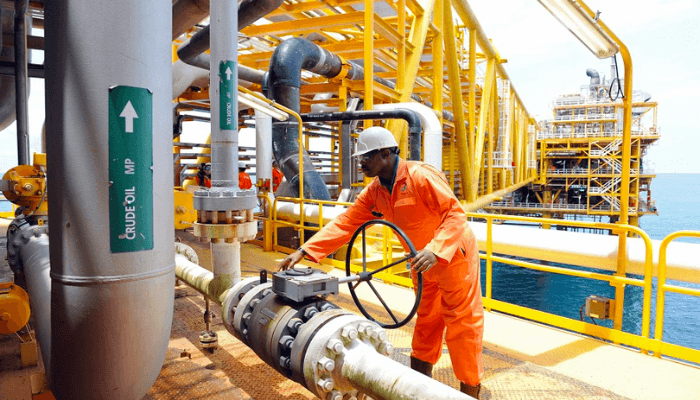

NigeriaŌĆÖs upstream petroleum sector is gearing up for another licensing round at the end of 2025, but industry players warn that unresolved structural weaknesses could produce yet another disappointing outcome.

The Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) officially commenced the six-month licensing exercise on December 2, targeting $10 billion in new investments and aiming to add two billion barrels to national reserves over the next decade.

The offering includes 15 onshore blocks, 19 in shallow water, 15 frontier assets, and one deepwater block, with the commission projecting 400,000 barrels per day production when fully operational.

However, a closer examination of the 2020 marginal fields bid round reveals a sobering reality that casts doubt on these ambitious projections.

Read also:┬Ā$17.4trn global upstream investment required in five yrs to avoid market deficit ŌĆō OPEC

Of the 57 fields awarded to 161 companies in that exercise, 33 licenses were subsequently revoked for the non-payment of signature bonuses.

More critically, available industry information indicates that only two fields have reached first oil to date, which are: Ingentia EnergyŌĆÖs Egbolom field producing approximately 2,300 barrels per day and Emadeb, which has just commenced production.

ŌĆ£It is very easy to point out the reasons for poor performance,ŌĆØ said a senior oil executive in the energy sector, who spoke to BusinessDay on condition of anonymity.

The executive identified four major structural impediments: indigenous operatorsŌĆÖ inability to raise development capital, the doubling of royalties under the Petroleum Industry Act from 2.5 percent to five percent for small producers, stringent requirements for infrastructure access negotiated with major oil companies, and uncertainty created by NUPRCŌĆÖs decision to merge multiple bidders with different operational plans and financial resources on single fields.

The capital access challenge stands out as perhaps the most critical barrier.

Capital remains the biggest barrier

James Akwaji, an energy analyst, noted that despite multiple bid rounds, from the 2003/04 and 2020/21 marginal fields exercises to the 2022/23 deepwater mini round and the 2024 PIA-era licensing round, actual production has consistently lagged projections.

ŌĆ£Despite the large number of oil blocks being offered across NigeriaŌĆÖs onshore and offshore basins, including the technically challenging deep offshore region, actual production has not fully matched the countryŌĆÖs hydrocarbon potential,ŌĆØ Akwaji observed. ŌĆ£Very few companies have announced that they have commenced production in their fields.ŌĆØ

Data gathered by BusinessDay show that between 2014 and 2019, when oil prices collapsed, credits from banks to the oil and gas industry dropped from $12.5 billion to $9.5 billion, representing a 24 percent decline. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN)ŌĆÖs sectoral limitations on bank portfolios have further constrained available credit, which fell from 28 percent in 2014 to 22 percent in 2019.

ŌĆ£Banks wonŌĆÖt fund marginal fields to first oil,ŌĆØ Olajumoke Ajayi, managing director of Ingentia Energies, stated candidly in a recent interview. ŌĆ£We had that experience. We wanted banks to fund, but they said the risk was too high, and they didnŌĆÖt fund. Our shareholders funded all the activities weŌĆÖve done to date from their pockets.ŌĆØ

IngentiaŌĆÖs achievement in reaching first oil in April 2024 at the Egbolom field represents a rare success story, but it came at significant cost.

The companyŌĆÖs shareholders provided equity funding through cash calls, bypassing the banking sector entirely. This model, while successful for Ingentia, is not scalable across the industry as most indigenous companies lack shareholders with sufficient capital reserves.

Read also:┬ĀUnderperformance of Upstream operators threatening NigeriaŌĆÖs energy sector- minister

Ikechukwu Ezerioha, involved in hydrocarbon accounting at Oasis Corporate Systems Limited, emphasised the scale of the challenge.

ŌĆ£The major challenge is definitely the huge and rising cost of developing these fields to production delivery. All stages of the front-end engineering design, development, planning and implementation are anchored by huge capital and investment costs.ŌĆØ

Infrastructure and regulatory hurdles

The infrastructure access problem compounds the financing challenge. Indigenous operators are expected to negotiate with international oil companies for access to pipelines, processing facilities, and export terminals ŌĆō infrastructure largely controlled by majors such as Shell, Chevron, and ExxonMobil. These negotiations often involve stringent technical and financial requirements that smaller operators struggle to meet.

According to legal analysis by Megathos Law Practice, the 2025 bid round awardees face five critical challenges: litigation with partners, technology limitations, regulatory uncertainty, environmental issues leading to community unrest, and increased cost of financing for deepwater projects due to security threats.

The regulatory uncertainty concern is particularly acute. Despite the approval of major transactions such as the ExxonMobil-Seplat and Shell deals, earlier delays and conflicting signals have exposed regulatory gaps. Nigeria only recently approved its first floating liquefied natural gas project, highlighting capacity and technology limitations within the regulatory framework.

Environmental and community relations issues also pose significant risks. Oil pollution, gas flaring, and inadequate benefit-sharing arrangements have led to community unrest in the Niger Delta, where most of NigeriaŌĆÖs oil resources are located. Indigenous operators often lack the resources and experience to manage these complex social dynamics effectively.

ŌĆ£So, since 2020, there has been no positive change: the same capital markets, the same infrastructure bottlenecks, and the same fiscal regime,ŌĆØ the senior oil executive, earlier quoted, told BusinessDay.

ŌĆ£NUPRC is selling licenses, not viable opportunities. Until they fix the fundamentals such as startup financing mechanisms, infrastructure access terms, and realistic fiscal frameworks, this new round will produce the same result: paper awards with minimal production.ŌĆØ

Read also:┬ĀLocal firms set to drive NigeriaŌĆÖs upstream renaissance

Forced marriages

The NUPRCŌĆÖs decision to merge several bidders with different operational plans, financial resources, and development strategies on single fields in the last bid round has created additional complications.

These Special Purpose Vehicles, formed by compelling winners to co-own assets, have been plagued by disputes over payment of signature bonuses and divergent operational visions.

ŌĆ£These winners do not know each other, have different plans and programmes and funding strategies, but have all been forced together in a union of strange bedfellows, which is frustrating the development of marginal oil fields,ŌĆØ a source close to one of the bidders told BusinessDay.

Industry stakeholders acknowledge that while the NUPRC has made improvements in transparency and process, the 2024 licensing round concluded without litigation and received commendations from the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI), transparency alone cannot overcome fundamental economic and structural barriers.

Ezerioha expressed cautious optimism, noting that ŌĆ£we should see more investment and partnership deals brokered with some of our indigenous companies for some of these milestone developments.ŌĆØ However, he did not specify what changes would facilitate these partnerships or how the financing gap would be bridged.

Read also:┬ĀNigeria regains top spot in AfricaŌĆÖs oil upstream investment

The success of the 2025 licensing round may ultimately depend on whether the government and the NUPRC can implement concrete solutions to these long-standing problems.

Options could include establishing dedicated financing mechanisms for small producers, mandating open and standardised access to infrastructure, providing fiscal incentives that offset higher operational costs for indigenous companies, and developing clearer regulatory frameworks that reduce uncertainty.

Without such interventions, Nigeria risks another cycle of high-profile license awards that generate revenue from signature bonuses but fail to translate into the production increases and economic benefits that the country desperately needs, experts say.