One impact of the financial crisis that has only recently become clear is the retreat of western banks from Africa. This, and diminished confidence in its traditional partners, lie behind Morocco’s unexpectedly energetic pivot towards its own continent in the past decade.

Now back at the centre of power, having stepped back after constitutional changes that followed the 2011 Arab uprising, King Mohammed VI has put business expansion and diplomacy across Africa at the centre of Morocco’s development strategy.

Cynics are right to observe that the rhetoric of “developmental states “and “south-south co-operation” has too often failed to meet African aspirations, as reflected in depressing data on regional trade, or on economic uplift for all but the elites. Big questions remain about the levels of risk implied in Morocco turning its sights southwards, but the trend cannot be ignored if one is to understand contemporary Africa.

Finance has provided a flagship for Morocco Inc, after the withdrawal, or scaling down, of international banks across Africa over the past decade created a vacuum that has been filled by Casablanca institutions. The commercial success of the big three — Attijariwafa Bank, BMCE Bank and Banque Centrale Populaire (BCP) — has been coupled with a recognition that Morocco could project its influence well beyond the west African countries with which it has historical links.

This process would help consolidate key national goals, including confirmation that the disputed Western Sahara is part of a greater Moroccan kingdom rather than a former Spanish colony aspiring to independence. Morocco’s new focus on Africa made restoring its membership of the African Union in January 2017 essential, ending a boycott dating back to 1984 after the rival Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) was admitted as a full member.

Those doubting the extent of Morocco’s ambitions in previously unfamiliar markets, from Egypt to Ethiopia and Nigeria, ignore a defined pattern of activity. It no longer seems unusual that one-third of Attijariwafa Bank’s profits come from other African markets, that phosphate giant OCP Group is investing heavily in Ethiopia or even that Rabat is planning a gas pipeline from Nigeria, a political rival, to the Mediterranean.

Initiatives like Casablanca Finance City have been fashioned to provide a platform for working in Africa. The hitherto domestically focused SNI, a holding company majority owned by royal interests, has been rebranded with an “African identity”.

Morocco’s applications — a surprise to some — to join the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) and its associated electricity market fit this logic. Similarly, Rabat’s commitment to the potential white-elephant gas pipeline and distribution system covering west Africa would feed its desire to become an energy hub.

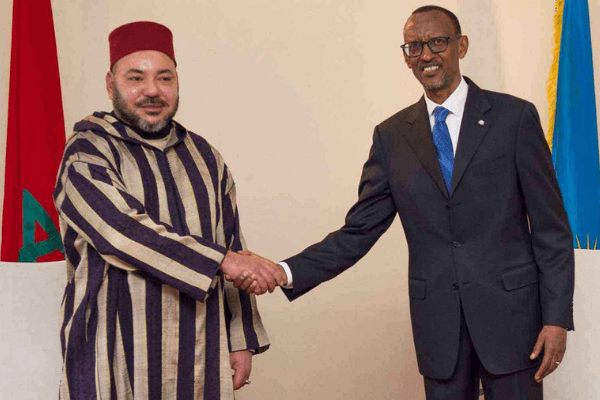

The pivot is not all about institutions, however. It has exploited historical ties, including close relations with leaders such as Ivory Coast’s president Alassane Ouattara and King Mohammed’s childhood friend Ali Bongo Ondimba, the Gabon president. The king’s line in multicoloured djellaba robes — a fashion statement appreciated by many Moroccans — and promotion of “moderate” Sufi Islamic values are a contemporary take on traditional links that span the Sahara.

One forward-thinking Casablanca banker admonishes those who say Sufi ties with west Africa are essential to understanding contemporary business. Yet others say Morocco’s identification with the north Africa-based Qadiriyya and Tijaniyya orders, which have a longstanding sub-Saharan presence, has enhanced its standing with leaders such as Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari.

King Mohammed has rightly made his focus on Africa results-based. The sacking last August of respected finance minister Mohamed Boussaid followed a colère royale, royal anger, at the lack of significant social and economic improvements for marginalised populations. The new minister, Mohamed Benchaâboun, emerged as a public figure by leading BCP into Africa.

Yet the king’s ambitions are not without risk. The Ecowas application has stalled. The pitfalls of building up sub-Saharan exposure by banks and big companies are discussed privately but played down publicly. Morocco is having to live with the SADR’S AU membership, which may complicate diplomatic ties with some countries.

Nevertheless, the conflict does not stop the kingdom pursuing ever more initiatives, over an ever wider spectrum of African regions and sectors. While Morocco’s new African strategy has been most evident in commercial deals, it also points towards the emergence of a genuinely post-colonial African order.