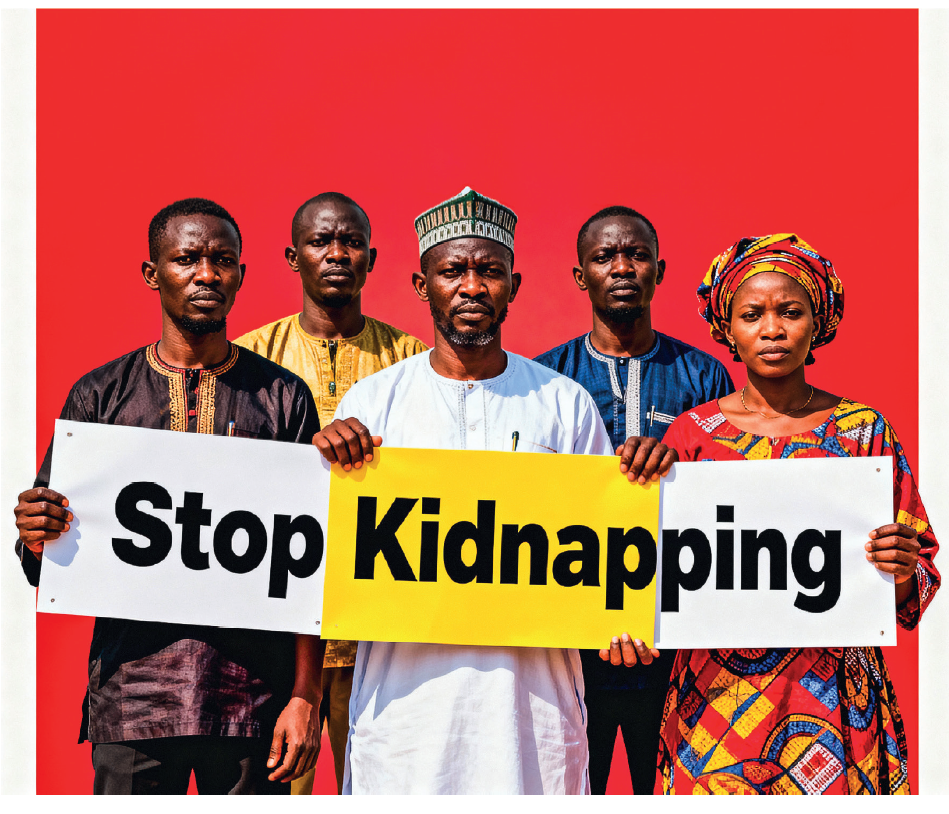

Just days before Nigeria’s 65th independence anniversary, precisely on 25th September 2025, 15 people were kidnapped while travelling from Calabar to Uyo via the Sea Express route. The incident added to the growing statistics of abductions across the country, spreading fear once more among ordinary Nigerians.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), between May 2023 and April 2024, about 2.2 million Nigerians were kidnapped, with roughly 65% of affected households forced to pay ransom. The average ransom per case was about N2.7 million, amounting to N2.2 trillion in a single year.

Economically, kidnapping drains billions from households, cripples trade and discourages investors. Businesses collapse under ransom burdens, while travel and logistics – especially by road – are paralysed, inflating costs nationwide. Socially, families live with trauma; some never see their loved ones again. Fear now shapes daily life, and ordinary travel is experienced with dread. Politically, the state’s failure to stop kidnappings weakens its legitimacy.

One figure who shaped the notoriety of kidnapping in Nigeria is the convicted kidnap kingpin, Evans, whose abduction-for-ransom empire revealed the criminal logic behind the trade. His story became an unsettling model for disaffected youths – a dangerous myth of wealth through crime. In the northern states, where poverty and illiteracy are more deep-seated, recruitment into kidnapping is even more rampant. The NBS notes that the North-West alone accounted for about 1.7 million victims between 2023 and 2024. Ransoms are often collected without interception, reinforcing a sort of belief that this trade is profitable and relatively safe for its perpetrators.

To dismantle this enterprise, Nigeria must end the commercialisation of crime; punishments for kidnapping must be harsher and consistently enforced. Strengthening the judiciary for faster trials and publicising convictions would deter offenders. Equally, detection and rapid response must improve. Too often, kidnappings occur without trace; technology such as GPS tracking, mobile triangulation, CCTV, drones, and community surveillance can change that. With trained officers, specialised units, and political will, Nigeria can build a justice system that delivers swift punishment and rescue – eroding kidnapping’s deadly appeal.

Regulating ransom payments is a crucial step. Families often have no choice but to pay, which sustains kidnapping as a business model. The government should monitor financial flows and freeze suspicious transactions. There has been massive failure in this regard, even though while insisting on no ransom payment, government has not properly educated traumatised relatives on how to respond during kidnap and ransom demand processes. A controlled and state-monitored method can both protect victims and expose criminal networks. Several countries already regulate ransom payments and Nigeria can adapt such models, balancing the need to save lives with discouraging ransom as an industry.

Beyond punishment and policing, socio‑economic reform remains essential. Kidnapping thrives because poverty and unemployment provide willing recruits. According to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS 2023), 40% of Nigerians live below the poverty line, and youth unemployment in the North‑West reaches 42%. Government must prioritise job creation, skills training, and targeted investment in high‑risk regions. Rural development should include infrastructure, schools, and social amenities. Education access must expand, especially in the Northern Nigeria, where low education level leaves youths vulnerable to recruitment. UNICEF’s 2024 Education Monitoring Report shows that net primary school enrolment in the North is only 60%, compared with 85% nationally. A young person who sees a credible path in education or employment is far less likely to be drawn into crime.

State presence must also be felt more strongly in neglected regions. Roads, electricity, communication networks, and security outposts must reach rural areas. When communities are less isolated, kidnappers lose hiding spaces. A 2023 Nigerian Police Force analysis found that communities with reliable electricity and mobile coverage reported 18% fewer kidnappings than those without. At the same time, police–community trust must be rebuilt. Many locals know the criminals but refuse to report them, fearing police corruption or inaction. Building trust through accountability, community policing, and partnerships with traditional and religious leaders is crucial. Transparency International’s 2022 Police‑Community Trust Index recorded a 30% increase in tip‑offs where such partnerships were active. When citizens cooperate with authorities, intelligence improves, and kidnappers find it harder to operate.

Transparency must also play a part. Government should regularly publish data on kidnappings, prosecutions, and rescues to show progress and regain public trust. The Office of the Inspector General’s 2024 Annual Security Report also recorded 2.2 million kidnappings as featured in the NBS report, and 1.4 million prosecutions in the past year. In addition, media and civil society groups must help stigmatise kidnapping, not romanticise it. Criminals must never be portrayed as “Robin Hoods.” Society must see abduction for what it is: a violent, parasitic crime that destroys communities.

Finally, Nigeria must collaborate regionally and internationally. Porous borders provide escape routes for kidnappers. Strengthening border control, using forensic technology, and partnering with neighbouring countries to track ransom flows can help. ECOWAS reported 152 arrests in the past 12 months through its Joint Border Security Initiative (2023). International cooperation on hostage rescue and intelligence sharing will further weaken the kidnapping economy.

Commercialisation of kidnapping will not end overnight, but it can be dismantled through a combination of tougher punishment, better policing, proper education on what to do with ransom demands, socio-economic intervention, and community trust. Most importantly, there must be political will. When the risks and costs of kidnapping outweigh the rewards, like any profit-oriented enterprise, the business will collapse.