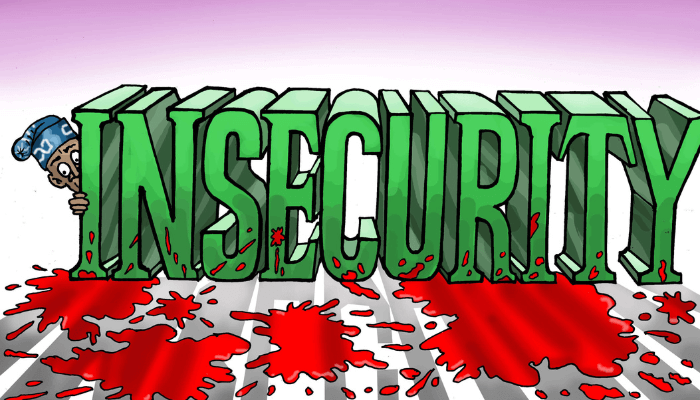

Insecurity remains NigeriaŌĆÖs most stubborn challenge, outliving successive administrations and shaping the daily realities of millions. Banditry, kidnapping, and terrorism have devastated communities, disrupted economies, and eroded citizensŌĆÖ trust in government. Despite repeated promises to confront these threats, the persistence of insecurity fuels suspicion that capacity is not the problem, political will is. Many Nigerians believe that powerful elites may be complicit in sustaining violence or unwilling to confront those who profit from it.

President Bola TinubuŌĆÖs recent declaration of a state of emergency on security has reignited debate about what genuine political will should entail. Similar proclamations in the past have yielded little change on the ground. The political will must be more than words; it must translate into concrete actions that disrupt criminal networks, even when those networks intersect with political and economic interests. It demands courage to confront uncomfortable truths, including the potential involvement of allies and influential figures in perpetuating insecurity.

For years, allegations have circulated that sponsors of terrorism and banditry include individuals in positions of influence. Naming and prosecuting such sponsors would send a clear message: no one is above the law. The anonymity of perpetrators and financiers has become a shield for impunity. However, this political will must pierce that shield to hold those behind the violence accountable; without such measures, insecurity will remain a profitable enterprise for those who thrive in chaos. Conspiracy theories of elite involvement are symptoms of a deeper crisis of confidence. Whether fully accurate or not, they persist because decisive government action has been lacking.

Read also:┬ĀNLC, CSOs protest insecurity in Jos, warn FG of nationwide shutdown

Recent leadership changes, notably the resignation of Defence Minister Mohammed Badaru Abubakar and the appointment of General Christopher Musa, former Chief of Defence Staff, signal recognition that new approaches are necessary. MusaŌĆÖs appointment is being closely watched as a test of whether leadership changes at the top can translate into more effective strategies on the ground. Such moves can symbolise political will, a readiness to replace officials who have failed with those believed to possess expertise and resolve, but symbolism alone is insufficient. Results, not appearances, must measure success.

Equally essential are funding and institutional reform. Nigerian security agencies have long suffered from underfunding, corruption, and inefficiency. A political will requires the courage to reform compromised institutions: sacking ineffective officials, restructuring bloated agencies, and investing in modern intelligence and surveillance technology. Oversight mechanisms must ensure that resources reach intended purposes, preventing diversion of funds that would otherwise strengthen national security.

Foreign involvement in addressing insecurity divides opinion. Some advocate for external assistance in intelligence, training, or operations; others warn that outsourcing security undermines sovereignty. A balanced approach is possible, where international partnerships enhance NigeriaŌĆÖs own capabilities in intelligence gathering, border security, and counterterrorism, while ensuring domestic leadership drives the strategy.

The judiciary must also function efficiently. Delays in prosecuting perpetrators and financiers allow suspects to escape justice and perpetuate cycles of violence. Political will must ensure courts are empowered and incentivised to handle cases of terrorism, banditry, and organised crime swiftly, reinforcing public trust in legal remedies.

Ultimately, political will must convince citizens that their leaders are acting in their best interest. Communities affected by violence must see tangible safety improvements. Farmers should be able to return to their fields without fear; children should attend school without risk of abduction; travellers should traverse highways without dread. Until these realities manifest, declarations will remain hollow.

Read also:┬ĀBeyond Bello TurjiŌĆÖs expos├®: The high cost of insecurity, PDP governors and the defection bug

NigeriaŌĆÖs insecurity is not insurmountable. Other nations have faced comparable challenges and emerged stronger. The difference lies in leadershipŌĆÖs willingness to confront the roots of violence rather than its symptoms. For Nigeria, this means addressing corruption, exposing sponsors, reforming institutions, and investing in communities. It requires refusing to normalise insecurity and demonstrating through consistent action that the safety of citizens is non-negotiable.

The utmost political will to curb insecurity must be uncompromising. It must challenge elites, reform institutions, uphold accountability, and acknowledge that insecurity is both a military and socio-political issue. Declaring a state of emergency is only the beginning. What follows, courage, transparency, and persistence, will determine whether the nation can break free from cycles of violence. Nigerians have waited too long for leadership that matches words with deeds. If true political will is finally summoned, insecurity can be curtailed, and the nation can begin to heal. Without it, the promise of peace will remain elusive.