Green dreams are accelerating, and the focus is shifting beyond oil production. Solar power, batteries, and electric vehicles are transforming competitiveness and trade. China has quickly combined innovation and policy to emerge as a global leader in electric vehicles (EVs). In May 2025, NigeriaŌĆÖs Minister of Solid Minerals Development, Dr. Dele Alake, announced ChinaŌĆÖs plans to establish EV factories, a move that could turn Nigeria from a resource supplier into a green manufacturing hub.

Beneath the surface lies a strategic advantage. Recent mapping by the Nigerian Geological Survey Agency has revealed a lithium belt extending from northwest to southeast, with some deposits containing up to 13 percent lithium oxide, significantly exceeding the standard exploitation threshold of 0.4 percent. Investor incentives, including five-year tax holidays, equipment duty exemptions, deferred royalties, and a 95 percent capital allowance, strengthen the investment case. EVs promise cleaner, quieter, and more efficient transport while emissions and operating costs squeeze households and businesses. Adoption is nascent and constrained by infrastructure, policy gaps, and financial constraints. The core question is whether market scale and policy intent will align to build a sustainable electric mobility ecosystem or consign the country to the global sidelines

┬ĀEmerging Demand

An ongoing transport revolution is gradually emerging, influenced by demographic trends and changing economics. The United Nations forecasts NigeriaŌĆÖs population to grow from 216 million today to 375 million over the next thirty years, a scale of growth that will reshape demand for mobility.

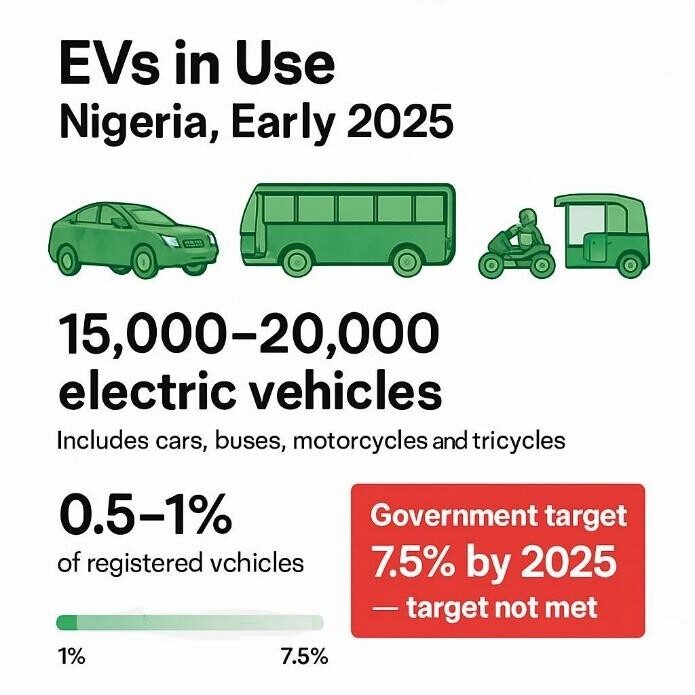

By early 2025, roughly 15,000 to 20,000 electric vehicles operate across the country, including cars, buses, motorcycles, and tricycles which accounts for about 0.5 to 1 percent of registered vehicles, a modest share that nonetheless marks a significant shift away from petrol and diesel dominance. Government ambitions aimed for 7.5 percent EV adoption by 2025 under the National Automotive Industry Development Plan (NAIDP), a target that remains unmet and highlights the shortfall in infrastructure and incentives.

Market research from 6Wresearch forecasts the sectorŌĆÖs compound annual growth rate at about 6.8 percent from 2025 to 2031, driven by expanding local assembly by firms like Spiro, SAGLEV, and Innoson, more supportive tax and import policies, rising fuel prices, growing interest in energy independence, and inbound investment in lithium battery production and EV components. The opportunity is real but delicate. Widespread adoption depends on addressing affordability, establishing charging networks, ensuring a reliable power supply, and raising public awareness. For investors and entrepreneurs ready to act quickly and creatively, coordinated policy and private capital can turn these emerging trends into lasting markets. Close collaboration now will determine who will capture the expanding mobility market.

The infrastructure reality

Electric mobility is gaining traction in Nigeria, yet the supporting charging infrastructure remains patchy and heavily concentrated in a few urban centres. A 2025 overview by Carlots.ng lists multiple commercial and pilot charging sites, especially in Lagos and Abuja, including recent additions such as roof-top chargers at the Mega Plaza Shopping Mall in Lagos.

Still, other sources indicate that publicly listed infrastructure is limited: for example, the ElectroMaps database shows fewer than 15 publicly registered charging stations nationwide.

On the supply side, power reliability remains a challenge. The national grid remains unreliable, with frequent outages and voltage fluctuations, as documented in academic studies of NigeriaŌĆÖs EV infrastructure. While regulators like the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) report incremental improvements in generation and regulation, large parts of the grid still fall short of consistent performance standards. A recent survey by Premiumtimes indicates that some households receive as little as 7 hours of continuous supply in certain states, though figures vary significantly by region and season.

Because of this, the places and ways charging hubs can reliably operate are limited. Many EV-charging deployments today lean on hybrid or solar-assisted systems in pilot formatŌĆörather than being fully integrated into robust grid-connected networks. For instance, rural or institutional pilots cite ~15 kVA solar setups rather than high-capacity grid-based fast-chargers

How Nigeria stacks up against its peers

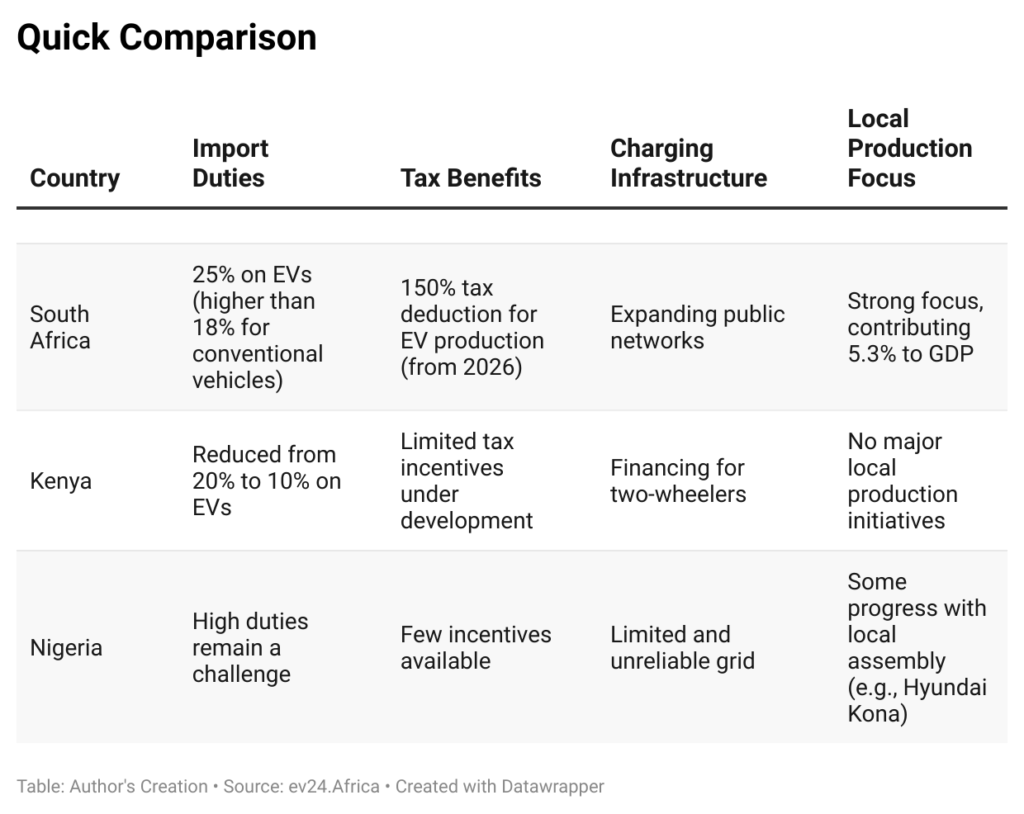

Regional comparisons make the policy gap impossible to ignore. South Africa leans on aggressive tax incentives and higher import duties to protect nascent local production, pairing a 150 percent tax deduction for EV production (from 2026) with expanding public charging networks and a manufacturing base that contributes meaningfully to GDP. Kenya is moving in the opposite direction on trade costs, cutting EV import duties from 20 to 10 percent while piloting targeted incentives and financing for twoŌĆæwheelers to boost urban uptake.

The table shows Nigeria trailing on every front: high import duties persist, few tax incentives exist, public charging is sparse, the grid is unreliable, and local production is limited to small assembly projects.

The investor and the policy playbook

A slowdown in global parts shipments is reshaping NigeriaŌĆÖs auto scene, forcing entrepreneurs and workshops to rethink their playbooks. Mechanics and assembly-line crews in Lagos report longer waits for battery modules and electronic control units,┬Ā a squeeze thatŌĆÖs pushing up repair bills and operating costs for small fleets, according to data from the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics. That disruption is nudging investors away from importing finished cars toward quicker, more practical bets: assembling vehicle bodies, integrating battery packs locally and electrifying targeted commercial fleets.

Startups building modular battery packs are gaining traction because their components are faster to move, test and certify than whole vehicles. Plans for dedicated charging corridors that prioritise buses and taxis are also attracting interest; predictable routes make utilisation easier to project and the business case clearer, a trend noted in recent industry analysis. Early fleet trials with electric vans are telling the same story: higher upfront prices but materially lower running costs per kilometre, a trade-off that appeals to cautious financiers looking for steady returns.

Policy remains the wildcard. The right mix of tax relief for assembly plants, expedited customs for battery cells and accelerated depreciation for charging hardware could flip the economics, as highlighted by observers including the World Bank. Clear safety and interoperability rules would prevent a fragmented market and reassure large buyers. Public procurement for municipal buses or postal fleets could provide the demand anchor investors crave. Watch for emerging assembly hubs, battery integration shops and charging-network rollouts, together theyŌĆÖll show whether Nigeria can turn disruption into an industrial leap.