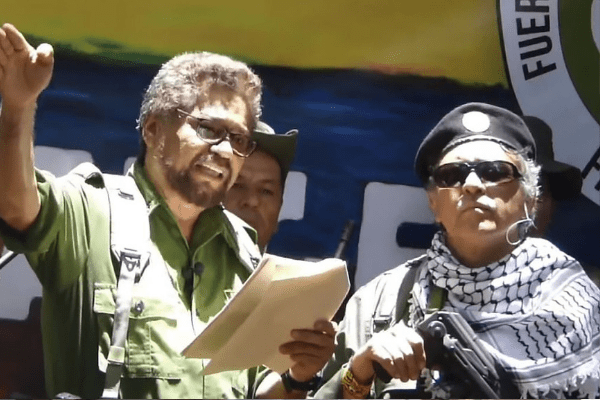

Avideo published on YouTube last week was a bleak reminder of Colombia’s violent past. It showed two dozen guerrillas in military fatigues in the jungle, guns slung over their shoulders, announcing that they were returning to war.

At their centre was Ivan Márquez, a longtime leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) and an architect of the group’s 2016 peace deal with the state after years of negotiations in Cuba.

Now Mr Márquez has accused Colombia’s government of “betrayal” of those peace accords. “This is the continuation of the guerrilla fight in response,” he said, flanked by his comrades.

It is the latest evidence that Colombia’s peace agreement is under threat.

Much of the country is still racked by violence, with Marxist guerrillas and rightwing paramilitaries active. Civilians are being displaced by fighting. Cocaine production is at an all-time high and social activists are being assassinated with alarming regularity.

This was not how things were

envisaged three years ago when the Farc and the government signed their agreement and heralded an end to half a century of conflict.

But since then, the government has changed and President Iván Duque’s rightwing administration is far more sceptical of the peace process. Prosecutors have pursued Mr Márquez for alleged drug-trafficking and he has slipped back into the jungle, accusing the government of betraying the Farc, culminating in his call to arms on Thursday.

It is unclear how much support he has. The Economist Intelligence Unit says his splinter group appears to number about 25-30 guerrillas, with no territory and few resources. In contrast, Control Risks believes the group has some 500 members and “is no idle threat”.

Much will depend on whether Mr Márquez can join forces with other Farc dissidents and rebel groups, notably the National Liberation Army (ELN), which was never part of the 2016 agreement and has continued its war against the state.

The Farc and the ELN both grew out of the same Marxist ideology in the 1960s but have fought against each other rather than in unison — usually over territory and control of drug-trafficking routes.