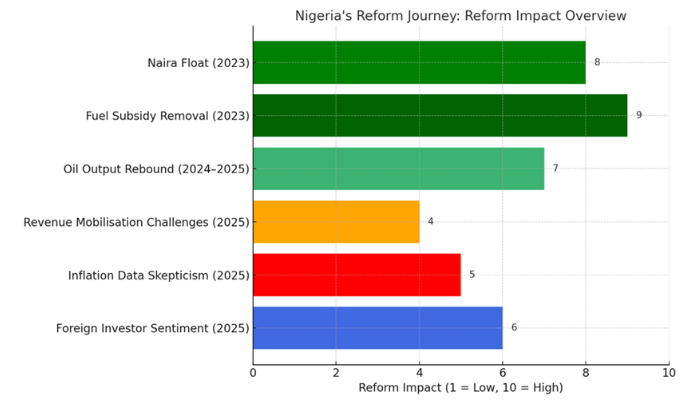

After nearly a decade of policy inertia, Nigeria’s economic regime has been jolted into life. A long-delayed naira float, the elimination of the fuel subsidy, and revived oil production suggest a government finally prepared to align with market logic.

But while the reforms are commendable, analysts warn that global shocks, weak revenue enforcement, and inflation distortions could stall the momentum.

Naira stability could be a mirage

The most transformative of the reforms has been Nigeria’s foreign exchange liberalisation. After years of multiple exchange rates, the decision to float the naira in mid-2023 was a significant signal to investors.

Initially, the naira depreciated sharply, touching N1,600/USD, but it has since shown signs of stability, too, perhaps.

Read also:¬ÝUtomi slams government‚Äôs revenue fixation, warns of economic mismanagement

“The Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) indicates Nigeria’s naira is now overvalued by over 25 percent, one of the most misaligned currencies in sub-Saharan Africa,” notes Renaissance Capital. “This could hurt exports and deepen the current account pressure over the medium term.”

Indeed, Renaissance Capital believes the naira may be heading into dangerous territory. If inflation is understated, the real exchange rate could erode competitiveness, a throwback to the overvaluation cycles of the 2010s that spooked foreign investors.

Despite this, portfolio flows remain positive, largely driven by short-term bets on equity recovery and expected yield in dollar terms.

Fuel subsidy removal creates fiscal room, but will it be used wisely?

The controversial removal of the petrol subsidy, a drain of nearly $10 billion annually, was long overdue. For years, it crowded out productive spending. Now, with that fiscal space supposedly freed up, expectations are high that the government will ramp up social investment. But actual performance tells a more nuanced story.

“The Central Bank of Nigeria’s monetary transmission mechanism, already fragile, remains largely reactive, with limited forward guidance to anchor expectations.”

Federal revenue surged by 103 percent in 2024 but slowed to just 11 percent in the first half of 2025, raising concern over revenue sustainability and execution delays.

“Revenue mobilisation is not just about removing distortions; it’s about institutional capacity,” says a public finance expert at the Password Professional. “Without aggressive execution of the new tax reform, both in administration and collection, the fiscal dividend may remain largely on paper.”

The budgetary pivot in 2025 was supposed to reflect these reforms, but social spending has not grown proportionally, and there’s evidence that capital expenditure has slowed due to bureaucratic bottlenecks and pre-election caution.

Oil output rebounds, but the price slump dampens the win

Oil remains central to Nigeria’s fiscal pulse, and on the production side, the signals are encouraging. After plunging to 0.9 mbpd in 2022, output has nearly doubled to 1.8 mbpd as of mid-2025. Yet, this bounce-back is undermined by persistently low global prices hovering around $64–66 per barrel, far below the ideal fiscal break-even levels of $75–85 per barrel for Nigeria.

“Volume recovery is crucial, but without higher prices, Nigeria will still struggle to meet its budget targets,” warns Fatima Yusuf, Senior Analyst at Consortium Research Intelligence. “The market outlook remains soft, with global supply outpacing demand, especially as Asian growth slows.”

This matters because while the current account surplus is expected to hit $14 billion in 2025, according to Renaissance Capital, Nigeria’s FX reserves are still eroding, likely due to high import demand and weak oil proceeds. Any future FX pressure will likely lead to renewed volatility, especially if monetary policy loosens heading into the 2026 cycle.

Inflation may be the silent saboteur

Official inflation stands at 22.22 percent, but analysts, including Renaissance Capital, argue that actual inflation may be significantly higher, based on observed consumption patterns and informal market dynamics. While they do not provide an exact figure, their concern points to a widening gap between official data and lived economic experience. This discrepancy distorts currency valuation, masks the true cost of capital, and weakens the credibility of monetary policy.

In such an environment, interest rate policy risks becoming ineffective. Negative real returns on government securities erode investor confidence, while capital flight and dollarisation pressures mount. The Central Bank of Nigeria’s monetary transmission mechanism, already fragile, remains largely reactive, with limited forward guidance to anchor expectations.

Read also:¬ÝNigeria economic reckoning: The long road from collapse to recovery

The IMF has echoed these concerns. In its July 2025 Article IV report, the Fund criticised the quality and timeliness of inflation data, citing delays in the full publication of rebased CPI figures and the selection of December as the index reference period.

This methodology, the IMF noted, “inhibits assessment of the inflation level and trend,” a technical flaw that undermines effective economic surveillance.

Sentiment vs. substance: A nation in mid-reform

Scepticism around reform is understandable but not always balanced.

Thus, the growing scepticism toward official data often appears one-sided. When macroeconomic indicators show improvement, critics are quick to question the numbers, but when the trends deteriorate, the same voices tend to fall silent.

“Must things always go bad in Nigeria?” asks a chief economist at a leading investment bank, who prefers anonymity.

“Investors returning capital is a signal of relief, not deception. Inflation easing may not immediately lift living conditions, but it’s a step forward.” This sentiment underscores the tension between perception and fact: while progress may be uneven, not all signs of recovery should be dismissed as statistical cosmetics.

Reform is real, but not yet irreversible

There’s no doubt that Nigeria has made more reforms in the past 24 months than in the previous eight years. These include long-delayed currency liberalisation, subsidy removal, and production-side recovery. However, these gains remain vulnerable to internal mismanagement and external economic shifts.

2026 may test the government’s credibility. If pre-election spending surges, revenue falters, and oil prices stay low, the naira may once again come under speculative attack. While foreign investors are cautiously optimistic, the next chapter of Nigeria’s reform story will depend not only on policies but also on execution discipline and trust in institutions.

The promise is real. But so is the risk.

¬Ý

Oluwatobi Ojabello, senior economic analyst at BusinessDay, holds a BSc and an MSc in Economics as well as a PhD (in view) in Economics (Covenant, Ota).