Nigerians rely on technology to keep their money, teach their children, protect their property; they just don’t trust it enough in choosing their leaders and end up paying a high price, writes ISAAC ANYAOGU.

The language of election sounds a tad similar to the language of war. Newspapers dress up headlines with euphemisms that have served battle-worn generals. Opponents are crushed in rival party strongholds and the ruling party is conquered in battleground states.

This is why elections in Africa’s biggest democracy stiran equal doze of passion and paranoia. On the eve of a general election, Nigerians stock up food and fuel and politicians move their families outside the country. The government shuts land borders, seaports and airports and enforce restriction on movement with armed soldiers. The feeling in the land is like that of a people under siege.

Any postponed election breeds frustration as everyone wants it over with. It also results in huge losses to the economy. This should make a strong case for using more technology in election management.

To gain a sense of how much economic loss Nigeria suffers because it cannot automate its election process, consider that the postponement of the Presidential and National Assembly elections on February 16 cost the economy over$1.16billion. This crude estimate divides Nigeria’s $427billion GDP in 2018 by 365 days in a year and calculating for one wasted day.

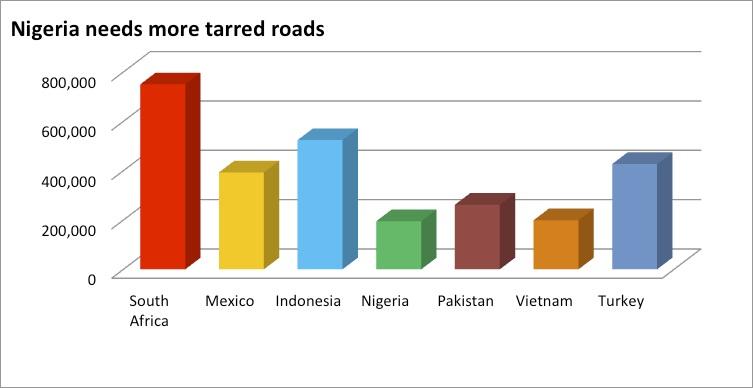

The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) blamed logistics. It is easy to see how this can happen. Nigeria has a total surface area of 923,768 km yet the country has only195,000km of tarred roads which compares poorly to South Africa’s750,000km.

Chidi Izuwah, director-general, Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission (ICRC), at a lecture in Abuja two years ago said about 135,000 kilometres of road network in Nigeria were un-tarred.

“Nigeria has about 195,000 km road network out of which a proportion of about 32,000 km are federal roads while 31,000km are state roads.Out of this, only about 60,000km are paved. Of the paved roads, a large proportion is in very poor unacceptable condition due to insufficient investment and lack of adequate maintenance.

Analysts say this is where elections start to fail. “In many parts of Nigeria, election materials will arrive late, not because of any fault of INEC but because of the poor state of our roads,” said Ayo Akinfe, a London-based writer and editor in a social media post.

But this is the very situation technology solves in other parts of the world. Indonesia will go to the polls in April this year but its terrain presents a study in what should constitute a logistical nightmare.

Indonesia is the world’s largest island country, with more than seventeen thousand islands, and at 1,904,569 square kilometres, the 14th largest by land area and the 7th largest in combined sea and land area. It is also the world’s 4th most populous country with over 261 million people.

Yet, the country’s General Elections Commission (KPU) will register 190million voters for its April presidential and national assembly elections. Sixteen parties will contest for 20,000 seats in parliament and local councils.

To combat this challenge, the country will rely on electronic voting, a plan it has been working on since 2014. According to the plan, the system would still require voters to visit polling stations, but to verify their identities and cast their votes.

“Citizens can just bring their electronic identification cards (e-KTP) to the polling stations,” said Marzan Iskandar, chairman of the Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology, according to Antara News.

According to Iskandar, “This platform will lower the cost of general elections by 25 percent, saving on ballot papers and cutting off the need for manual labour. Digital voting will help eliminate fraud and will return voting results within minutes. The government plans to strengthen cyber security to protect electoral data.”

There is a yawning need for technology in the management of Nigeria’s election but the electoral law has failed to keep up. In 2017, lawmakers passed the Electoral Act No. 6 2010 (Amendment) Bill 2017 which among other things gave INEC unfettered powers to conduct elections by electronic voting. The House of Representatives kicked against it, the president withheld assent and INEC said it needed more time.

“If tomorrow the bill is assented to… there are provisions that we cannot implement simply because of time. For instance, full blown electronic voting. It is impossible within the time-frame available which is 112 days,” Mahmood Yakubu, INEC chairman said.

The argument against electronic voting in Nigeria relies on cost, availability of electricity and the fear that uneducated rural folks could be excluded. But these concerns are largely naive.

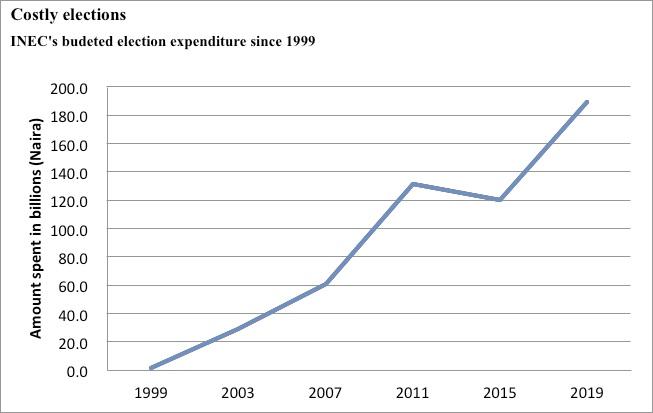

It is definitely not cost, because Nigeria’s 2019 elections of which 73million people have been accredited to vote would cost US$625 million which is more than the US$600 million spent on India’s 2014 elections where 553.8 million people voted electronically.

In India, locally made Electronic Voting Machines(EVMs) have replaced paper ballots in all elections. To check calls for abuse, the Election Commission introduced EVMs with voter-verified paper audit trail (VVPAT) system, which is essentially a printout of results.

India’s EVM, which costs US$580 in 2017 can record 3840 votes and cater to 64 candidates. It consists of a control and ballot units. Balloting unit has buttons which indicates voting details and the control unit stores vote counts and displays results.

Rural India has millions who are uneducated and the machines are so simple, they require just pressing a button against a political party. Folks in rural Nigeria use ATMs and make mobile money transfers and operate smart phones which are all more complicated than pressing a button.

EVMs in India can transmit results back to the Election Commission but the facility was disabled to prevent intrusion during electronic transmission of results. Results are stored in the machine and party officials sign off. When election closes, no one can alter the results.

EVMs have saved India billions of dollars hitherto used in printing ballot papers, cut the number of staff and remuneration, promote faster counts and cancel out double voting. It comes with a battery unit that lasts between 10 and 14 hours a day on a full charge and has a shelf life of 15 years. This takes care of electricity concerns.

INEC is deploring 400,000 adhoc staff from the National Youth Service Corps who only constitute 40percent of its staff. It is spending N1.4billion to buy ballot boxes and N35billion to print ballot papers and result sheets. Electronic voting will cut these costs.

Analysts say fear about security is exaggerated. “I think it is a trust issue,” says Sodiq Alabi, a communications officer at Paradigm Initiative, a Lagos-based digital rights advocacy. “This is an environment where people do not even trust the physical paper, how much more an electronic system.”

To tamper with the machine in India, a hacker will need physical access to them which is difficult due to security. He will also have high tech skills. Besides, one will need to manipulate thousands of machines to impact an election, which is almost impossible given the hi-tech and time-consuming nature of the tampering process. The company that manufactured the machine relinquished control after being acquired by the state.

In Nigeria alone, there are over 119,000 polling units, and if such machines are in use, a hacker has to gain access to over 50,000 to seriously impact an election outcome.

“We have the capacity to produce the machine and even domesticate it and this will make rigging difficult,” Alabi said.

Analysts say political will is what is lacking. Politicians spend billions in ‘mobilisation’, a euphemism for any vice from vote buying to paying thugs to snatch ballot boxes. Electronic voting will check this and no government, no matter its claim to piety, is willing to change this.

Political parties who lose general elections are the first to call for reforms of the electoral process and the application of more technology but when they get into power, the agitation fizzles out.

This happens because every political party hopes to benefit from the crude electoral process which is susceptible to manipulation. Every party wants the block votes from the north, even if herds of cattle are counted rather than humans.

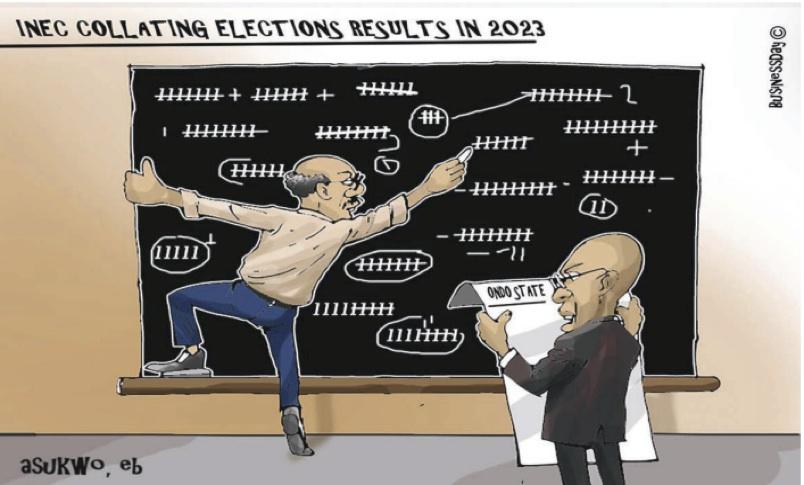

Recourse to paper allows for underage voting and for a party official to thumbprint a million ballots. When the card reader machines fail, there is no failsafe way to prevent abuse. Ballots are not even checked for double voting using fingerprint technology at collation centres.

In a country, where politicians have nothing to convince voters of their good intensions, deception appears an attractive option.

In 2019, Nigerians have to travel to vote in areas they were registered and state returning officers fly to Abuja to read results because of a stubborn refusal to leave the stone-age and embrace technology.

ISAAC ANYAOGU