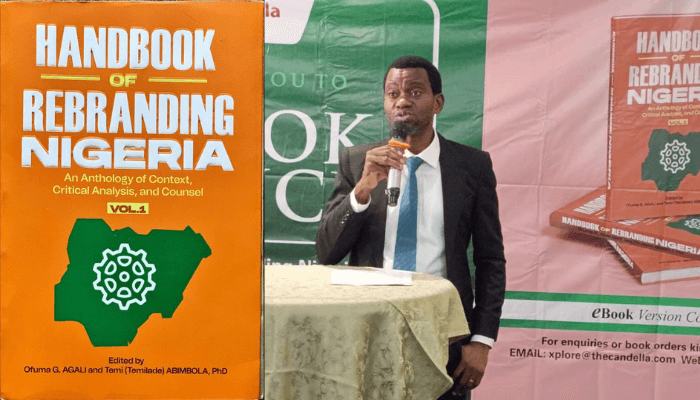

Ofuma G. Agali and Temi Abimbola, eds. (2025). Handbook of Rebranding Nigeria: An Anthology of Context, Critical Analysis, and Counsel. Vol 1. Ikeja, Lagos: Candella Content Services Limited. 392 pages.

Reviewed by Chido B. Nwakanma

The Handbook of Rebranding Nigeria arrives as a monumental and ambitious project, the culmination of a 15-year effort involving 55 contributors. This first volume, organised into ten parts and 58 chapters, offers a comprehensive examination of Nigeria’s persistent, and often challenging, attempts to manage its national image from 2005 to 2016.

Scope and Ambition: An Encyclopaedic Journey

The handbook’s most immediate feature is its extensive scope. Covering nearly 400 pages, it analyses the Nigerian experience through the perspectives of history, sociology, politics, culture, management, diplomacy, and communication. It documents important branding campaigns from the foundational “Heart of Africa” project to the more widely recognised “Good People, Great Nation” initiative, offering a valuable record of the nation’s dialogue with its own image.

The roster of contributors reads like a who’s who of the Nigerian public sphere, featuring figures such as Prof. Kayode Soremekun, Funmi Iyanda, Biodun Shobanjo, Dr. Kayode Fayemi, Dr. Josef Bel-Molokwu, and the late Prof. Emevwo Biakolo. It also includes Jeremiah Agada, Olubayo Adekanmbi, Akin Adeoya, Charles O’Tudor, Ikem Okuhu, Lugard E.A. Aimiuwu, Uche Nworah, NtiaUsukumah, and Desmond Ekeh. Others are Nnanke Harry Willie, Salisu Ahmed Koki, Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah, Malcolm Fabiyi, Chuks Oluigbo, and Itose Okosun.

Lead editor Ofuma Agali’s vision was to create a definitive repository, gathering disparate voices on brand Nigeria into “one easily accessible basket,” serving as a “go-to resource, refresher, and a general call to action.”

Agali collected contributions across three sequences, aiming for publication within 50 years of Nigeria and, if not, to commemorate the Nigerian centenary in 2014. It has finally seen the light in 2025.

Agali explains, “Part one chronicles the journey to becoming Nigeria. Part Two reflects on the merits and demerits of amalgamation, while acknowledging that the country has become what it is, nonetheless. Part Three reviews Nigeria at independence, shedding light on issues perceived to have the potential to escalate if left unchecked, and the opportunities that presented themselves to the new country. Part Four examines the foundations of nation branding on both theoretical and practical levels, including tangible and intangible factors, and how these apply to rebranding Nigeria.”

“In Part Five, the Heart of Africa project comes into focus”, highlighting the prospects and flops as “Nigeria’s first conscious external branding effort”. Part Six puts “Good People, Great Nation” in the spotlight. Arguably, the most notable rebranding effort in Nigeria, this part is the largest. Everything that could have worked and everything that could go wrong, and which went wrong, came in view in multiple dimensions and contexts”.

Agali states the two-fold solution of the book: gather all the contributions on rebranding Nigeria and “organise these materials into one easily accessible basket as a representation of the voices that have spoken out concerning matters of brand Nigeria and rebranding Nigeria.”

Flagship Insights and Thematic Depth

The anthology is rich with incisive commentary. Akin Adeoya, in “Brand, Nation, and Truth,” establishes a foundational principle: branding is a “progression from the generic to the particular,” with differentiation at its core. Olubayo Adekanmbi’s “Timeless Continuum of The Lord Lugard Stereotype” brilliantly introduces technical marketing dimensions, analysing Brand Nigeria through four historical layers, weaving politics and communication into the brand narrative.

The book serves as a valuable reference, providing clear analyses of past campaigns. It presents intriguing alternative viewpoints, such as the essay by positioning gurus Al Ries and Laura Ries, who argue that factual differentiators like “Largest and Greenest” would have been more effective than the aspirational “Good People, Great Nation” in attracting global attention.

Their argument is: “What will get you in the mind is standing for something that differentiates you from the rest”. They added, “When people perceive you as the largest, the media is much more likely to pay attention to you, to write stories about you, to write stuff about the good people and great nation of Nigeria.”

Many of the essays provide insight, illumination and education.

No fewer than ten essays address the matter from a public relations perspective, with some from a journalism and storytelling angle. This was before the advent of the term “content marketing.”

However, the book’s format as a static physical volume poses a practical obstacle in our digital age. The lack of a digital footprint for individual essays diminishes their accessibility and usefulness for researchers and practitioners who operate online. It must catalogue its contents for this era. When learning that his essays appear in this long-awaited book, one author immediately requested a link. Each essay needs to be notarised with digital footprints.

Ofuma however argues against such digital breakdown. He thinks it will defeat the essence of searching far and wide to put the essays into a collection.

The uplifting news for digital natives is that an e-version will soon be available to overcome the limitations of physical copy.

The Critical Challenge: A Document of Its Time

However, the handbook’s greatest strength also serves as its main weakness. As a collection of essays conceived in the analogue era and published in the digital age, it feels both chronologically and conceptually outdated. While invaluable as a historical record, it lacks detail on the technical aspects of modern, data-driven nation branding.

The field has developed into a sophisticated discipline where strategy, policy, and communication intersect, as reflected by comprehensive global indices such as the Anholt-Ipsos Nation Brands Index (NBI)and the Global Soft Power Index (GSPI). Other indexes include the FutureBrand Country Index (FCI), Reputation Lab’s RepCoreNations and the Good Country Index (GCI).

The review of Nigeria’s current position—83rd in the CEOWORLD 2026 Reputation Index, alongside poor rankings in governance (116th out of 120 on the Chandler Index) and corruption (140th out of 180 on Transparency International)—highlights how much the discussion has moved beyond the campaigns analysed in the book. The lack of comparative case studies (e.g., South Africa, Turkiye, the UAE) and a framework grounded in modern measurement tools underscores this gap.

In contrast, Nigeria was among the Top 50 countries in 2013 when Jossy Nkwocha wrote “Building Nigeria’s Reputation and The Good News From Barcelona”. It is one of the essays in the book. Nigeria was ranked 47th. Nkwocha and Sina Odugbemi participated in the 17thInternational Conference on Corporate Reputation, Brand Identity, and Competitiveness in Barcelona, Spain. The Reputation Institute is one of the main organisations involved in the nation branding and reputation sector, and they organised the conference.

Verdict: An Indispensable Foundation, Awaiting a Sequel

The Handbook of Rebranding Nigeria is an essential scholarly and professional resource. It delivers significantly on its aim to compile and contextualise a key period of national self-reflection. The encyclopaedic scope of its content makes it a foundational text for anyone aiming to understand the historical roots of Nigeria’s branding challenges.

Ultimately, this handbook is not the definitive guide on rebranding Nigeria, but rather the essential first volume. It offers the vital background, lessons learned from past failures, and the intellectual foundation needed for a modern, data-informed, and strategic rebranding endeavour. It serves as a crucial primer on the past, patiently awaiting the sequel that will explore the future.

The field has developed into a sophisticated discipline where strategy, policy, and communication intersect, as reflected by comprehensive global indices such as the Anholt-Ipsos Nation Brands Index (NBI)and the Global Soft Power Index (GSPI). Other indexes include the FutureBrand Country Index (FCI), Reputation Lab’s RepCoreNations and the Good Country Index (GCI).

The review of Nigeria’s current position—83rd in the CEOWORLD 2026 Reputation Index, alongside poor rankings in governance (116th out of 120 on the Chandler Index) and corruption (140th out of 180 on Transparency International)—highlights how much the discussion has moved beyond the campaigns analysed in the book. The lack of comparative case studies (e.g., South Africa, Turkiye, the UAE) and a framework grounded in modern measurement tools underscores this gap. Bola Akingbade’s essay looks at UAE and South Africa in Chapter 50.

In contrast, Nigeria was among the Top 50 countries in 2013 when Jossy Nkwocha wrote “Building Nigeria’s Reputation and The Good News From Barcelona”. It is one of the essays in the book. Nigeria was ranked 47th. Nkwocha and Sina Odugbemi participated in the 17thInternational Conference on Corporate Reputation, Brand Identity, and Competitiveness in Barcelona, Spain. The Reputation Institute is one of the main organisations involved in the nation branding and reputation sector, and they organised the conference.