In Wole Soyinka’s The Lion and the Jewel, Sidi’s choice between Lakunle’s hollow modernity and Baroka’s cunning traditionalism mirrors Nigeria’s developmental crossroads. The nation, much like Soyinka’s heroine, has long vacillated between imported shortcuts and self-serving nostalgia, each path deepening poverty and inequality. Yet China’s metamorphosis — from an agrarian society to global powerhouse — offers a blueprint for transcending this false binary. The answer lies in constructing and emphasising three interlocking infrastructures: cultural, political, and trade. Together, these form a bridge between tradition and progress.

Cultural infrastructure: Immanent innovation in practice

China’s rise was rooted in immanent innovation — treating tradition as a living scaffold rather than a relic. At its core, immanent innovation recognises existing cultural and economic systems as assets rather than obstacles. Agricultural modernisation did not begin by dismantling communal farming practices but by incrementally introducing hybrid seeds and mechanisation while preserving village cooperatives. Rural industries, once centred on handicrafts, evolved into manufacturing hubs by integrating global supply chains without abandoning local networks.

Nigeria’s struggle stems from a failure to see its own cultural fabric as infrastructure. Consider the vibrant mai shayi tea stalls of Kano or the cooperative esusu savings circles: these are not mere traditions but systems of trust and exchange. Yet policies often dismiss them as backward. Imagine if Nigeria formalised esusu networks into microfinance hubs or equipped mai shayi vendors with solar chillers to reduce waste. The informal markets of Alaba International, often labelled chaotic, could become innovation clusters — akin to China’s “street stall economy”— if supported with targeted upgrades.

China’s reforms worked because they treated culture as infrastructure. Similarly, our strategy need not reject tradition but refine it. The error lies not in evolving systems but in viewing culture as a relic rather than a renewable resource. The lesson is clear: development cannot thrive by erasing the past. Like a palimpsest, progress must layer new meaning onto existing cultural scripts, ensuring Sidi’s agency is not sacrificed for someone else’s vision.

Political infrastructure: The alchemy of local governance

China’s hybrid governance model fused centralised planning with localised execution, enabling national poverty goals to adapt to regional realities through a balance of autonomy and accountability. By delegating authority to counties and townships — while rigorously evaluating officials via performance metrics and “paired assistance” programmes — China ensured that its centralised vision did not stifle local ingenuity. Empowered bureaucracies in Guizhou leverage mountainous terrain for tourism, while Ningxia harnesses arid landscapes for solar farms, demonstrating that execution thrives when local tiers are equipped to lead. This model transformed governance from abstraction to action.

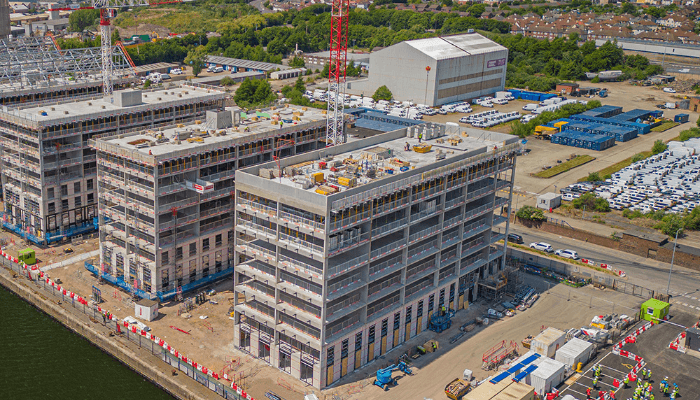

Nigeria’s recent Supreme Court ruling granting financial autonomy to local governments is a step forward, but paper reforms cannot mask institutional decay. Most local government councils lack basic tools: no GIS for mapping infrastructure, no digital systems to track healthcare data, no trained staff to maintain schools. Analogue record-keeping cripples service delivery, while untrained workers leave clinics under-staffed. China’s counties thrive because they are equipped — armed with digital tools, skilled bureaucrats, and cross-regional mentorship. For Nigeria, political infrastructure demands more than autonomy; it requires digitising workflows, training council staff in data analytics, and fostering civic participation through town hall apps. Only then can local governance shift from a hollow tier to an engine of accountability.

Trade infrastructure: Weaving urban, rural, and global threads

China’s most striking feat — narrowing its urban-rural income gap — hinged on treating connectivity as a right. Investments in roads, cold-chain storage, and broadband allowed villages to sell cherries to Shanghai and wool to global markets. “Taobao villages” like Sangpo, once isolated, became hubs of e-commerce by plugging local herders into digital supply chains. This integration did not erase rural identity; it amplified it, proving tradition and technology need not clash.

When digitising rural commerce through platforms like Pinduoduo, it did not impose foreign e-commerce templates. Instead, it reimagined village trade networks, where farmers in provinces like Yunnan and Sichuan now use digital marketplaces to sell lychees and chili peppers directly to urban consumers, bypassing costly intermediaries. This “social commerce” model thrived because it honoured China’s collectivist ethos, turning cultural logic into economic leverage. This ecosystem — bolstered by subsidies, land reforms, and digital literacy programmes — reduced the rural-urban income gap from 3.3:1 to 2.5:1 (2009–2020). Crucially, it reshaped migration patterns: as rural incomes rose, young people showcased thriving small-town lives on Douyin, proving that earning well in low-cost areas could rival urban opportunities.

Nigeria’s spatial inequalities, however, reflect fractured trade infrastructure. Lagos’ glittering tech hubs coexist with Sokoto’s subsistence farms because rural areas lack passable roads, storage facilities, and broadband. Middlemen exploit this disconnect: tomatoes rot in Kadawa while Lagosians pay triple the price. Informal social commerce — WhatsApp traders in Onitsha, Facebook hustlers in Aba — hint at potential, but without state support, these networks remain fragmented.

Nigeria must prioritise urban/rural integration. Reviving NIPOST, expanding rural cold storage, and enabling private sector investment in logistics will be the backbone of sustainable development. Meanwhile, formalising social commerce — through digital hubs training farmers and artisans in e-marketing to access national and global markets — would mirror Pinduoduo’s democratising effect.

Conclusion: A paradigm shift

Sidi’s dilemma — like Nigeria’s — is a false choice. The path out of poverty lies not in Lakunle’s borrowed scripts or Baroka’s selective cunning but in building three infrastructures that honour the past while forging the future. Cultural infrastructure transforms traditions into systems of innovation, layering technology onto communal practices. Political infrastructure empowers local governance with tools and accountability for locally sensitive policymaking. Trade infrastructure weaves physical and digital bridges, turning rural producers into global players.

China’s playbook shows that development is not a rupture but a dialogue. For Nigeria, this means rejecting both the contractor-driven “progress” of white elephants and the elite capture masked as tradition. It demands rewriting the narrative — one where Sidi leverages cultural resilience, accountable governance, and inclusive trade to craft an ending worthy of her promise. The task is urgent: without these pillars, cities will keep bursting, inequalities will fester, and the jewel of Nigeria’s potential will remain trapped in someone else’s tale.