Brandford Griffiths sat at his writing table. It was early in the morning, just a few minutes after five o’clock. It was a time that he favoured for contemplation, especially when his soul was troubled, as it was at this moment. He loved the soft play of the breeze from the Marina as it wafted in through the window of his study. From here, he could feel the life and energy of Lagos around him. Sometimes he would sit at the little table for hours, composing his despatches, or doing nothing in particular.

He had been Lieutenant Governor of the Gold Coast, with responsibility the Lagos Colony for almost four years now. With a rueful smile, he reminded himself he had even been acting governor of the Gold Coast and the Colonies, including Lagos, for a spell. He had counted himself exceptionally lucky to be given the top post so early and had looked forward to being confirmed in the substantive position, with all the perquisites that would follow, including a Knighthood. But Her Majesty’s Colonial Service had other ideas. Samuel Rowe was brought in as Governor in March 1881. That was when he was shoved downstairs – to Lagos, as Lieutenant Governor.

His time would come, assuredly, he told himself, sighing, as the breeze from the lagoon played on his face.

He turned up the wick of the lamp on the table, adjusted the writing paper before him, and dipped his pen in the inkpot.

He was composing a letter to the people of Ikorodu. It was his way to bring closure to the most troubling crisis he had faced since his tenure in Government House in Lagos.

“To Apena and other Chiefs of Ikorodu” he wrote, at the top of the page.

“Government House, Lagos, 25th February 1884”

“Apena, Kasimawo, Balogun, Seriki and other Chiefs of Ikorodu

I received your letter of 16th February 1884 and read it with attention…”

He paused as he reflected.

He loved Lagos, loved the sheer exuberance of the people, for good or for ill. But just like the tropical weather, trouble – whenever it came, did not drizzle, it poured.

Two weeks ago, in the dead of night, on Saturday the 11th of February 1884, a group of men had set off in canoes from Oke Popo, Lagos Island, heading to Ikorodu. They were armed to the teeth and driven by one objective – to wreak havoc and carnage. There were about sixty of them, from all credible accounts.

They were led by a man named Ilo. It would emerge later that he, and several of the men who followed him, were originally inhabitants of Ikorodu, who had left the town under a cloud.

A major diplomatic incident was in the offing, as Ikorodu – though a place of regular interchange for trade, was technically outside the purview of the colonial authority of Her Majesty’s government.

Disruption of a trade route to the interior, perhaps even war, was imminent, if he – Brandford, did not handle the matter with the delicacy it deserved.

He smiled grimly, recalling the strident tone of the letter fired to him by the Apena and other Ikorodu notables on February 16th.

“…invaders under British Protection landed at 3am Sunday while (we were) fast asleep with our families…Balogun’s house… surrounded and set on fire…200 other houses burnt…firing guns…killing 10…wounding some…”

Though Ilo and a number of his men had lost their lives in the assault when the Ikorodu people rallied and fought back, the Apena and other Chiefs demanded “severe punishment” for the surviving offenders who had escaped back to Lagos, and their suspected backers, including some prominent Lagos Chiefs.

The sun was beginning to rise as Brandford composed his missive, trying to strike a balance between firmness and compassion.

“…I have already expressed to you my regret at the suffering you have met with by the hand of the band of ruffians you defeated…they (the attackers) like all other people in Lagos, enjoy the protection of her laws…as in all civilised communities…government cannot tell all the people who are constantly coming and going from Lagos…26 of them have been committed for trial at the next Assizes…the utmost powers of the law will be put in force to punish offenders…”

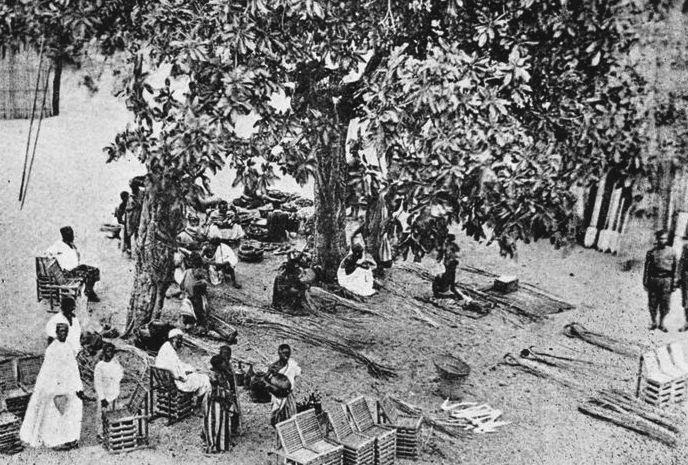

Indeed, a few days after the incident, he had personally travelled to Ikorodu on the government steamer “Gertrude” on a mission of condolence. He had gone with Inspector Forbes and a force of 20 Houssa Constabulary. Of course, he had taken the precaution of issuing 20 rounds of ammunition to each of the men. Docking at the quay, they fired a gun to announce their arrival and proceeded into Ikorodu town with a marching band, drums rolling. There, he had held a “palaver” with the Balogun and his chiefs. They had exchanged gifts, and he had left Ikorodu as evening fell.

It was already dark when he returned to Lagos, and he had had to wait until the moon rose before the steamer could berth safely.

His visit alone should have been enough to calm Ikorodu nerves, he reasoned.

He really hoped the matter would go away, he decided, concluding his letter now by assuring the Ikorodu chiefs that the severity of the punishment to be meted out to the captured men would deter other people from contemplating such dastardly adventures in the future.

“…Your sincere friend

- Brandford Griffith

Lieutenant Governor of the Gold Coast Colony”

He appended his signature with a flourish.

It was already morning. He walked to the window and surveyed the bright Lagos skyline.

A quick bath, a cup of tea, and then the office.

Some day he would be Governor. He would be made a Knight of St George by Her Majesty, Queen Victoria. But that was still in the future.

Meanwhile, there was all this work to be done – in Lagos.