It might not have been his intention, but Julian Richer recently became a socialist hero. In May this year, the owner of the hi-fi and TV retail chain, Richer Sounds, did something that does not happen very often. He transferred his controlling stake in the business with its 53 stores to a trust for the benefit of its 530 staff.

It was not a political gesture. Mr Richer, 60, has no children and simply wanted to ensure that the company he built up over 41 years had a stable succession. “My father dropped down dead at 60, so I was keen for this to happen in my lifetime,” he explains.

Creating an employee trust a bit like John Lewis Partnership, the famous UK retailer, wasn’t an easy choice. It cost Mr Richer the chance to sell for the highest price to private equity or a trade buyer. Instead he flogged the shares to the trust at concessionary rates.

He did so partly to reward his employees who had helped him build the business. But it wasn’t just sentiment: Mr Richer also felt they would be better stewards of the business than a distant and financially driven investor.

“We own 90 per cent of the stores as freeholds, and I didn’t want someone selling those off at the first opportunity to pay a dividend,” he says.

Employee ownership has historically been the minority choice among British businesses. With its £200m in sales for the last financial year, Richer Sounds is one of the largest of the 350-odd companies to have adopted the employee ownership trust (EOT) model.

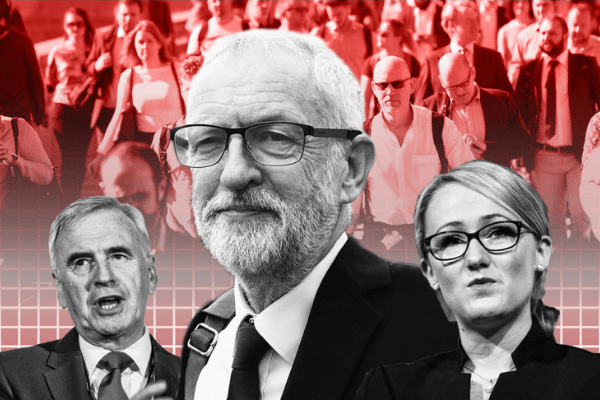

But it is a path the Labour party hopes to encourage many more to take in the future. Under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, Britain’s opposition is seeking not just to change corporate governance, but the way British companies are financed and owned.

“It is about building a new model of economic democracy,” says James Meadway, an economist and former adviser to the shadow chancellor John Mcdonnell.”

“We need to look beyond the old dichotomy of ownership between private sector and public sector, and engage with the wide range of options that lies in between.”

Ownership has always been central to Labour’s credo. Ever since Sidney Webb, the social reformer, wrote Clause IV of its 1918 constitution, calling for workers to secure control of “the means of production, distribution and exchange”, such questions have preoccupied the party’s thinking on economic issues.

True, there was a hiatus under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, when these ideas were dropped as outmoded, and the “filthy rich” enjoined to pay their taxes. But under the leadership of Mr Corbyn they have come roaring back.

Much of the public focus has been on nationalisation as the flagship of this new ownership agenda. In the autumn of 2017, Mr Mcdonnell promised to bring “ownership and control of the utilities and key services into the hands of people who use and work in them”. Labour has identified natural monopolies such as water, electricity transmission and rail, as well as the Royal Mail postal service, as targets for state buybacks.

But the agenda goes far beyond nationalising utilities. Labour thinkers believe they can tap into the same desire to “take back control” that drove the Brexit vote to push through far-reaching changes designed to give staff a greater say in the places where they work.

“Just as nationalisation underpinned the postwar consensus and privatisation drove Thatcherism, new pluralistic and democratic models of ownership will be vital to moving beyond neoliberalism,” says Mathew Lawrence, an influential figure in Labour circles and founder of the Common Wealth think-tank.

Part of the strategy is to promote alternative structures to the dominant public limited company model, which Labour argues leans too much towards the primacy of external shareholders.

The idea is that worker ownership could spur greater productivity by allowing workers to participate financially in its fruits. Placing a lock on the assets — workers would get the economic and voting benefits of ownership, but not the right to sell the shares, under the Labour proposal — would create the commitment that is often absent in conventional shareholder ownership.

Proponents such as Rebecca Long-bailey, the shadow business secretary, claim this would limit the ability of owners to push down wages and cream off excess profits — a traditional critique of shareholder capitalism that has been revived loudly in recent years by academics such as Thomas Piketty.

She also believes it could help industry adjust to the sweeping changes that lie ahead as Britain deals with such challenges as artificial intelligence and decarbonisation. “A worker would have a very different decision mechanism in looking at their job over the next 20-30 years as against a shareholder who may have a very short- term measure,” says Ms Long-bailey.

Such an approach includes forgoing dividends if workers could see investments being raised that would increase productivity and make them better off. “It is something that already happens in workplaces where there is high worker engagement,” she adds.

Evidence suggests that companies with greater levels of worker ownership are both more stable and willing to tolerate long payback horizons on investment. A review by Cass and Manchester business schools in 2017 concluded that such firms had “either superior or similar economic performance” to non-employee owned firms. This became more marked at times of economic stress.