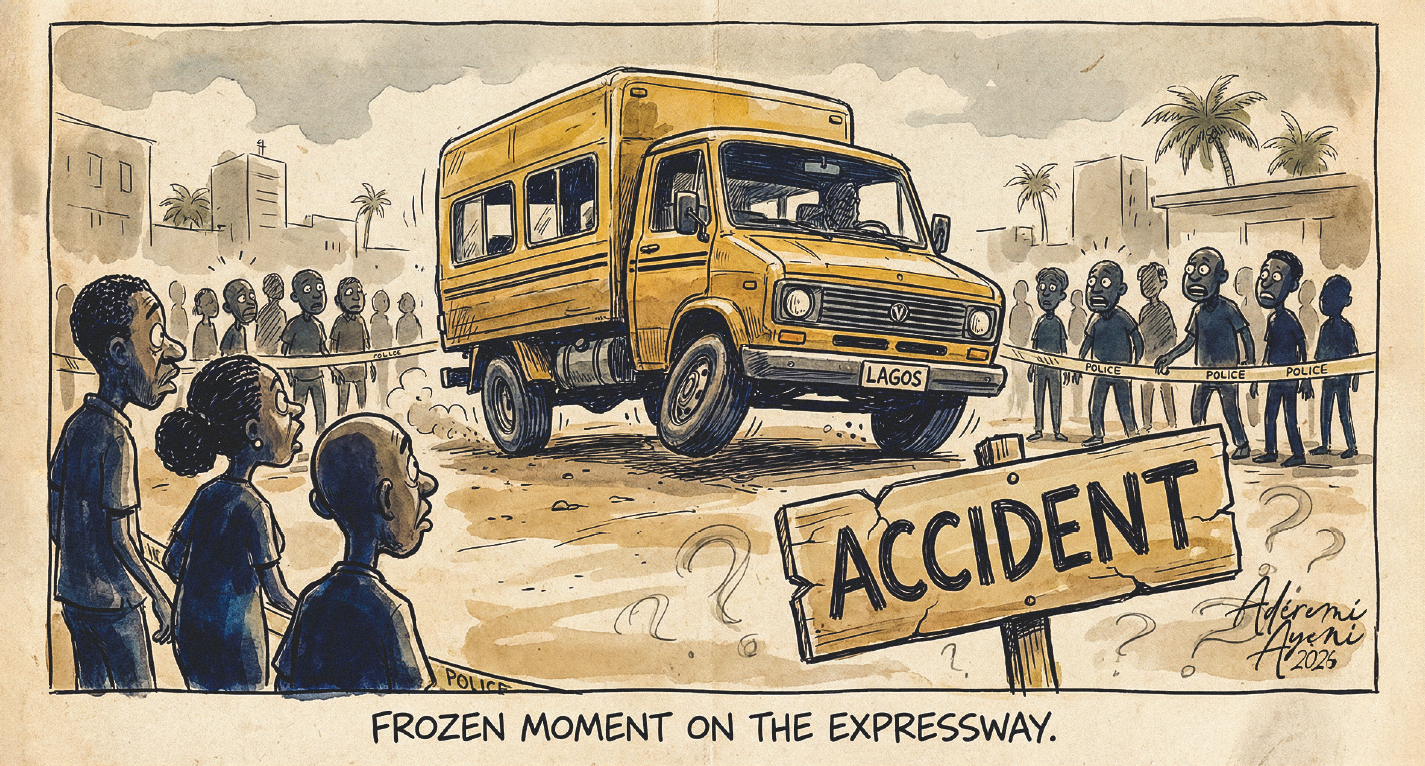

In Nigeria, when a truck or car hits pedestrians or public gatherings, causing injury or death, the incident is almost reflexively classified as a “road accident.” In some cases, families of victims are often compensated by truck owners or drivers’ employers; police file routine crash reports; and life moves on as if the deaths were unfortunate but singular events. Even fatalities involving dozens of people are folded into annual road crash statistics without further investigation into motive or pattern. This approach obscures a critical question: what if some of these events are not random tragedies but indicative of a deeper pattern of vehicle-into-people violence?

According to the World Health Organisation, Nigeria records one of the highest road traffic death rates globally, estimated at 21.4 deaths per 100,000 people, well above global averages and among Africa’s worst. In practical terms, Nigeria recorded 5,421 deaths and 31,154 injuries from 9,570 road crashes nationwide in 2024. Federal Road Safety Corps data show that about 5,000 people are killed and over 31,000 injured annually. Between January and September 2025 alone, 3,433 deaths and 22,162 injuries occurred in 6,858 crashes. These figures represent parents, students, traders, pedestrians, and children lost each year, yet most cases are classified as “accidents,” obscuring two analytic concerns: first, a subset involves vehicles ramming into crowds; second, repeated crashes around predictable events or locations challenging the assumption of randomness.

In parts of northern Nigeria, particularly in Gombe State, a pattern of repeated vehicle-into-crowd incidents has emerged over several years, especially during Christian processions such as Easter and Christmas. In April 2019, a vehicle ploughed into a late-night Easter procession of Boys’ Brigade members, killing at least 10 children. On Christmas Day in December 2024, a commercial bus ran into a Christmas procession in the same state, injuring at least 22 people. Of particular significance is the April 2025 Billiri Easter Monday incident, where investigations concluded that a trailer truck driver deliberately drove into a Christian procession, killing at least six persons and injuring more than 30.

Taken together, these incidents, occurring in the same state, during similar religious events, and over a six-year period, set Gombe apart from Nigeria’s broader road-crash background and raise the analytic possibility that certain vehicle impacts may be systematically oriented rather than purely random, especially when viewed alongside global precedents.

In Nice, France, in 2016, a 19-ton cargo truck was deliberately driven along the Promenade des Anglais during Bastille Day celebrations, killing 86 people and injuring 458. The attack was claimed by Islamic State, and its characterisation as a vehicle-ramming attack shaped subsequent urban security policy and legal responses. In Berlin later that year, a hijacked truck was driven into a Christmas market, killing about 13 people. In Stockholm in 2017, a truck rammed through a pedestrian street, killing five people. Similar attacks have also occurred in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Across these global cases, the analytic commonality lies not merely in the use of vehicles, but in the eventual recognition of intent and target selection through investigative and legal processes. In many Western contexts, vehicle ramming has been incorporated into domestic counterterrorism frameworks or prosecuted under criminal statutes that recognise willful mass violence. It is precisely this analytical evolution, from “accident” to “tactic of violence,” that Nigeria’s security and policy institutions have yet to undertake.

While not classified as intentional ramming, the recurrent crashes involving heavy trucks around Adekunle Ajasin University in Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, reveal another pattern that challenges Nigeria’s accident-only framing. Between 2020 and 2025, multiple heavy truck collisions in the same corridor resulted in repeated fatalities and injuries. These include a rice-laden truck ploughing into a roadside market in October 2020, a multi-vehicle collision in December 2020, a Cement truck of popular company lost is brake control in January 2021, subsequent crashes in April 2021 and February 2022, and another cement truck crash in October 2025 that killed eight people, including women and children.

At present, Nigeria’s road safety and security institutions treat nearly all vehicle-into-person fatalities as accidental collisions. There is little systematic inquiry into whether some incidents involve deliberate harm motivated by sectarian tension, grievance, or other factors. The consequence is that families often receive only compensation settlements rather than justice, and governance blind spots persist where predictable patterns of harm go unexamined.

Globally, vehicle ramming has been recognised as a tactic favoured by violent actors because it requires minimal planning, exploits everyday infrastructure, and is especially lethal in crowded spaces. Once identified as intentional, it triggers specific prevention strategies, urban design changes, and security coordination. In Nigeria, determining intent may be difficult, but the absence of structured inquiry is more dangerous than uncertainty. Law enforcement must adopt investigative protocols that distinguish negligent accidents from potential intentional ramming, particularly in cases showing repetition or event-specific targeting.

Nigeria’s experience with vehicle-related fatalities is a tragedy of scale, but within that tragedy lies an analytically urgent question: are some of these deaths random, or are they manifestations of violence that institutions have failed to recognise? The Gombe and Akungba-Akoko cases demonstrate that recurring harm, especially when predictable in timing and location, cannot be dismissed as coincidence. Recognition is the first step toward prevention. Without it, future deaths will continue to be subsumed under the language of “accident,” thereby delaying the policy and security reforms needed to save lives.