Lagos State’s demolition of Makoko’s waterfront has left thousands displaced and linked to multiple deaths, including a newborn. In this report, BusinessDay documents how a safety operation widened into mass displacement and raises questions about accountability in Lagos’ urban renewal drive. Royal Ibeh writes.

Mansur Atiba, 45, believed he and his household were safe. His wooden house stood on stilts above the brown waters of the Makoko Lagoon, far from the edge where government officials said demolition would stop.

From his doorway, Atiba could count the distance in paddles and footsteps, nearly 200 metres away. Well beyond the line. That belief gave him peace.

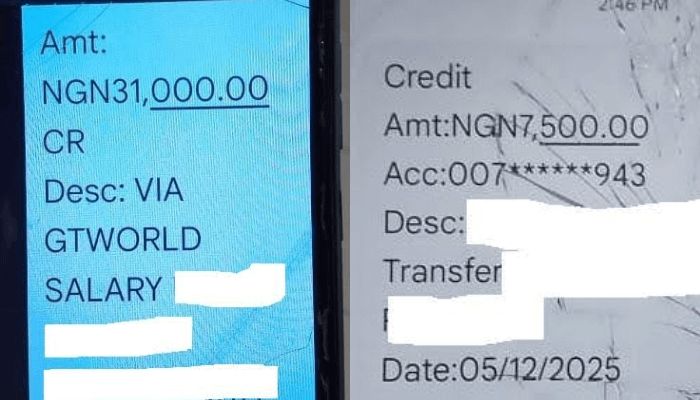

For years, he had lived on the Makoko waterfront the way his father had lived, and his father before him, as a fisherman, rising before dawn, paddling his canoe into the lagoon, casting his nets into familiar waters. His wife stayed behind, smoking the fish and selling them to traders who paddled from shack to shack. The money was never much, but it was enough.

“Enough for food. Enough for dignity. Enough for happiness,” Atiba told BusinessDay.

A child arrives

Early last year, they decided it was time to start a family. By March, 2025, his wife was pregnant. Neighbours celebrated. “In Makoko, a child is not just born into a family, it is born into a community,” Atiba affirmed.

Women checked on her. Elder fishermen prayed. Atiba worked longer hours, pulling heavier nets, determined to provide.

On the night of December 19, just after midnight, his wife went into labour. By morning, Atiba was holding his child. “I wrapped the newborn in cloth, cradling the tiny body against his chest. Five fingers. Five toes. A soft cry. The weight of responsibility and joy settled into me,” he stated.

For five days, the child lived

Five days in which Atiba barely slept. Five days of naming ceremonies whispered and postponed. Five days of imagining a future, school, fishing lessons, a life better than his own. Then the bulldozers came. “‘It will not reach us. The government said 100 metres’ I told my wife”.

That was the agreement residents believed they had reached with officials: homes within 100 metres of power lines would be cleared. Atiba measured the distance himself. His home was almost 200 metres away.

He was confident; so confident that on the morning demolition resumed, he left his wife and newborn inside their wooden home and went to help a neighbour dismantle his roof, trying to salvage zinc sheets before the machines arrived.

Then everything changed. “Without warning, police officers deployed tear gas,” Atiba stated.

The canisters hissed as they hit the water and wooden walkways. Smoke rose and spread quickly, trapped by the narrow alleys and still air. People screamed. Children cried. Mothers ran.

“I heard it from a distance. So I dropped the zinc sheet and ran. By the time I reached my home, my wife was coughing violently. The baby, five days old, was convulsing. The child’s chest struggled to rise. Foam gathered at the mouth,” he stated.

Atiba panicked. He wrapped the baby tighter and ran, first by canoe, then by road, moving from one hospital to another. They needed oxygen. There was none. “Hospital after hospital turned us away. The baby died on the way to Island Maternity Hospital. I don’t understand how joy could vanish so completely,” he lamented.

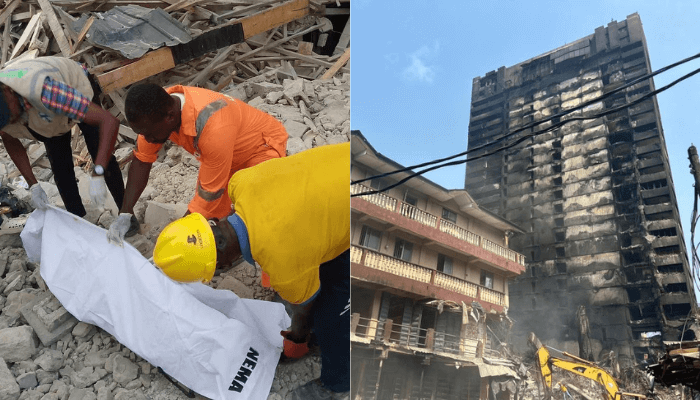

Atiba’s baby was one of at least five lives claimed since the demolitions began on December 23, 2025, in Makoko Waterfront, according to reports from residents, civil society groups, and eyewitness accounts. Among the others were two additional babies and a 70-year-old woman named Albertine Ojadikluno, who succumbed to shock, injuries, or related distress.

Lives upended, no shelter left

For many residents, the aftermath of the demolitions is a daily struggle for survival. During a recent visit, BusinessDay discovered that displaced families now sleep in canoes or makeshift boats tied together on the lagoon.

When it rains, water soaks clothes, bedding, and children huddled under thin tarps. When the sun beats down, the open water becomes a furnace, with no shade or relief.

For Mrs. Funmi Alao, a displaced resident, the demolition began on an ordinary day. She woke before sunrise, as she always did, to the smell of lagoon water and damp wood.

Her husband had returned late the previous night with a modest catch: tilapia and croaker pulled from the lagoon after hours of paddling in the dark. Funmi’s plan was simple: smoke the fish, sell some to nearby traders, keep enough to feed her children, and use the little profit to buy garri before prices rose again.

She lit her fire early, arranging the fish carefully on the wire mesh over the smoking drum. The children were still asleep inside the wooden house perched on stilts above the water. It was a routine she had repeated for years, one that had kept her family afloat in a city that rarely noticed them.

Then she heard shouting. “At first, it sounded distant, like the usual arguments on the water. Then came the sound of engines, heavy, metallic and the unmistakable crack of tear gas canisters.

“There was no warning. No one told us to move. They just came,” Funmi tells BusinessDay, her voice flat with exhaustion.

Panic spread quickly along the narrow walkways. People grabbed children, cooking pots, fishing nets, whatever they could carry.

Funmi rushed back into the house, pulling her children awake, their eyes wide with fear as smoke seeped through the wooden slats. “I tried to return for my belongings, but the tear gas burned my eyes and throat. I abandoned the fish, my family’s food and income for the week; all was lost,” she decried.

By the time she reached the water, bulldozers were already tearing through nearby homes. Planks splintered. Roofs collapsed into the lagoon. Canoes bumped violently against one another as people scrambled to escape. “We couldn’t retrieve our belongings. My children have no clothes. We have no food. We cannot fish. And yet, they still come to tear gas us,” she says.

Today, She and her children sleep in a canoe tied to others for balance. When it rains, they are soaked. When the sun rises, there is no shelter. She no longer smokes fish; there is no firewood, no drum, no place to stand. Her children ask when they are going home. She has no answer. “What kind of safety is this? Is it safety when your children are sleeping on water?” she asks quietly.

Evangelist Isaac Dosugan, 75, a lifelong fisherman, embodies the generational bond to Makoko.

Living in a simple shack with his wife and four children, he relies on his canoe known as “our car,” to feed his family.

“Government officials have repeatedly told us different things… Why? What is the purpose? Do you want to wipe us out?” he asked.

Dosugan says he received no prior notice before the demolitions escalated, with structures destroyed over water well beyond agreed limits.

Israel Idowu, a community organizer, insists that there was deception at the heart of the operation.

He notes, “Residents marked the 100-metre boundary themselves, using Nigerian flags and their own money, cooperating peacefully. But operators admitted they had no instructions about the 100 metres. The real order was to clear the entire waterfront. The 100 metres was a cover-up.”

He also warn of threats, arrests, and internal betrayal by parties leaking information to authorities..”

Rodrick Oluwatosin Iyinde, a fisherman and community member, highlighted Makoko’s vibrancy.

He reveals, “Makoko is not just water. It is an island of hardworking people, fishermen, artisans, traders, students, and labourers.”

Iyinde complied with initial setbacks, 30 metres, then 50, then 100, even dismantling his own school to salvage materials.

Yet, the destruction continued, shutting schools, demolishing churches and hospitals, and leaving people stranded on boats amid pervasive fear.

Negotiating with power, losing everything – Baales

Traditional leaders and the Baales, express displeasure with the demolition, saying they negotiated in good faith, trusting government assurances, only to see demolitions expand and leave families homeless.

For Shemede Emmauel, Baale, Makoko Waterfront, the destruction of Makoko was not sudden, it was a slow betrayal.

As a traditional chief, Emmanuel had spent months in meetings with government officials, community leaders, and security agencies. When the Lagos state government announced plans to clear areas under high-tension power lines, he took the message seriously. He gathered residents. He urged cooperation. He believed dialogue could protect the community.

“We were told it was about safety. Thirty metres. Then fifty. Then one hundred. We agreed because we wanted peace,” Emmanuel recounts.

Under his supervision, residents marked boundaries themselves, using Nigerian flags and stakes purchased with their own money. Families dismantled homes within the agreed limits, salvaging wood and zinc sheets in painful but orderly compliance.

Emmanuel attended meetings, made phone calls, and relayed assurances back to the community. Again and again, he was told the demolition would stop at the agreed setback.

Then the bulldozers crossed the line. “They did not listen anymore. They did not call us. They did not explain,” he says.

As machines moved deeper into the waterfront, Emmanuel tried to intervene. He approached officials on site. He reminded them of the agreements. He asked for time, for restraint, for humanity. “All to no avail,” he says.

Homes beyond 100 metres fell. Churches collapsed. Schools were destroyed. Families who had complied watched everything they owned disappear into the lagoon.

Emmanuel’s own home, where generations of his family had lived, was threatened. Fishing nets, canoes, and communal spaces that sustained the community were wiped out. “I was born here. My father and grandfather were born here. Fishing is our only source of livelihood. When you destroy this place, what do you expect us to become?” he tells BusinessDay.

As a Baale, Emmanuel carries responsibility without power. He negotiated in good faith, trusted government assurances, and urged calm. Now, he stands among displaced families with nothing left to negotiate.

“We are not against development. But development should not make people homeless. It should not kill children. It should not turn leaders into liars in the eyes of their people,” he says.

Felix Fasinu, a traditional chief in Makoko Waterfront, standing outside his home amid ongoing threats, echoed the community’s vulnerability: “We are not powerful.”

As bulldozers continue to reshape Makoko’s waterfront, residents say the cost of Lagos’ urban renewal is being paid in lives quietly, on the water, far from the offices where the decisions are made.

Findings by BusinessDay reveal that the demolition has displaced thousands from Makoko’s historic waterfront, a community of over 80,000 to 100,000 people where fishing sustains families, canoes serve as streets, and homes perch on stilts above the lagoon.

Repeated pattern of dispossession

The tragedy in Makoko is the latest chapter in a cycle of forced evictions that has reshaped Lagos’ informal settlements over the past five years.

For years, communities have been caught between promises of safety and the harsh reality of bulldozers, tear gas, and sudden displacement since 2020.

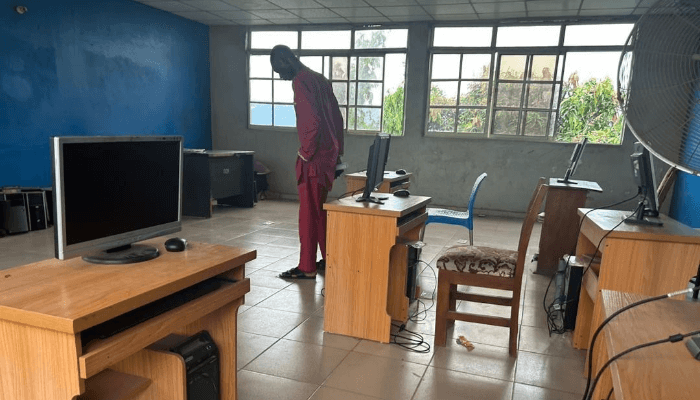

2020: Monkey Village (Oregun, Ikeja) – Demolished on New Year’s Eve with just 15 minutes’ notice; community centers, including an ICT hub and children’s library run by CEE-HOPE, were destroyed using alleged fake court documents.

“Over 400 residents were displaced, shattering livelihoods and exposing families to poverty. No direct deaths were reported during the operation, though long-term health impacts from sudden homelessness affected vulnerable groups like women and children,” Betty Abah, the executive director of CEE-HOPE told BusinessDay.

July 2023 onward: Oworonshoki (initial waves) – Starting in July 2023, demolitions targeted waterfront communities under the Third Mainland Bridge, including Itesiwaju Ajumoni, Ojulari, Ososa Extension, and Toluwalase Extension.

“Thousands were displaced in night-time operations involving bulldozers, tear gas, and armed enforcers. Reports indicate at least 10 to 22 deaths overall from 2023-2025 phases, including direct fatalities, resulting from residents crushed in homes or dying from heart attacks amid chaos and aftermath effects like stress-related illnesses leading to blindness or death,” Abah stated.

She highlighted specific cases which include a newborn, a 5-year-old, a 15-year-old girl, and an elderly man named Avoyonkentomakpa who died days after displacement in December 2025, attributing these deaths to excessive force and lack of warning.

February 2024: Orisunmibare: This community is part of the escalating waterfront clearances. According to Abah, structures were razed without adequate notice, displacing low-income families, adding that, “No specific deaths were reported, but the operation contributed to broader patterns of trauma and economic loss in informal settlements.

March 2024: Otto communities: Demolitions focused on unauthorized shanties near infrastructure, Abah said, adding that, “Residents faced sudden evictions. No direct deaths were documented, though injuries from confrontations were noted in broader reports on Lagos’ eviction crisis.

September 2024: Oko Baba and parts of Aiyetoro: Abah said bulldozers targeted sawmills and residential shanties in these areas, displacing traders and families reliant on the timber trade. “No confirmed deaths from this specific phase, but it exacerbated vulnerabilities in nearby communities like Makoko, leading to heightened risks of poverty and violence,” she stated.

March 2025: Ilaje Otumara, Baba Ijora, and neighboring areas: Tragic demolitions razed over a century-old settlement near Ebute-Metta and Apapa Road, with bulldozers entering at dawn accompanied by police and “area boys” armed with machetes. “At least 9,000 to 10,000 people were displaced in a single day, destroying homes, businesses, and places of worship. Investigations were launched into the deaths of two children, allegedly linked to tear gas exposure and the chaos of the operation, though official confirmation remains pending. This event highlighted the violent standards of Lagos evictions, with residents given only moments to flee,” she stated.

September-December 2025: Massive evictions in Oworonshoki: Intensified operations cleared nearly the entire waterfront and inland areas, displacing tens of thousands. “This phase contributed to the overall death toll of at least 10 to 22 reported across Oworonshoki evictions (2023-2025), including fatalities from direct violence, heart attacks, and post-eviction distress. One notable case was the death of an elderly resident shortly after displacement in December,” Abah affirmed.

December 23, 2025 onward: Makoko phase: Began with a 30-metre setback from power lines but intensified on January 5, 2026, extending far beyond (up to 500 metres in some areas), displacing over 10,000 residents and destroying schools, churches, and hospitals.

“At least three deaths were reported: 70-year-old Ms. Albertine Ojadikluno (from shock or injuries) and two babies, including five-day-old, who convulsed amid tear gas and chaos, dying en route to hospital). These fatalities underscore the humanitarian toll,” she lamented.

Overall, these demolitions have displaced hundreds of thousands since 2020, with a cumulative death toll in the dozens across reported events, often linked to tear gas, structural collapses, heart attacks, or post-eviction hardships.

Human rights groups like Amnesty International highlight a pattern of impunity, urging independent probes and compensation.

Abah links this to a wider pattern over the past year, including Oko-Baba, Ayetoro, Otumara, Baba-Ijora, Oworonshoki, and Precious Seeds, often without notice, consultation, or alternatives and in defiance of court cases.

‘Development without resettlement is not progress’

Human rights groups, including Amnesty International, say the demolitions reveal a consistent disregard for legal protections and human dignity.

Civil society leaders describe the operations as inhumane and a form of land grabbing, carried out without notice, consultation, or resettlement.

Nnimmo Bassey, director of the Health of Mother Earth Foundation, called the destruction of Makoko a profound shame, accusing the government of colluding with private interests to treat residents as human scrap for elite profit. “Destroying Makoko will not erase its history. This is a massive violation of human rights,” he states.

Abah says demolition itself is not inherently wrong if it is genuinely carried out in the public interest.

She notes that governments, have a responsibility to ensure safety, enforce planning regulations, and protect citizens from environmental and infrastructural risks. However, she stresses that such actions must be guided by humanity, transparency, and respect for human dignity, especially when they affect already vulnerable populations.

Recall that during the Babatunde Fashola’s administration, attempts were made on urban renewal, as some slums were affected. One of such slums was Ejora-Badia, where the governor had to provide alternative accommodation for a good number of people, before demolishing the shanties.

“The same should play with the Makoko people. No one is against the plan of the Lagos state government to turn Lagos state into a ‘mega city’. What we are against is when the people are displaced without fair compensation, resettlement plans or any form of support to help them rebuild their lives,” Abah stated.

She warns that forcing families, particularly women, children, and the elderly, into homelessness exposes them to hunger, violence, exploitation, and long-term trauma. In her view, development that leaves people stranded on water or sleeping in the open cannot be described as progress, insisting that any urban renewal programme must put people first, not afterthoughts.

Wetland loss, sand-filling, and climate vulnerability

BusinessDay gathered that the demolitions coincide with pressures on Lagos’ wetlands, vital for flood absorption, water purification, and biodiversity.

Numerous studies confirm significant wetland conversion due to rapid urbanization, with severe losses in Lekki (42 percent between 2011-2022), Akoka (19 percent between 2013-2022), and Badagry Creeks (29 percent between 2013-2021).

Drivers include sand-filling for housing/infrastructure, leading to increased flooding, habitat loss, and degradation.

A study on land reclamation in Eti-Osa and Lagos Island (1992-2022) showed increases in built-up areas and bare land, with wetland reclamation contributing to urban growth but recommending green infrastructure and sustainable drainage to mitigate floods.

Nenibarini Zabbey, a professor of biomonitoring and restoration ecology in the Department of Fisheries at the University of Port Harcourt, has warned that sand mining and reclaiming of wetland areas are major contributors to flooding in Nigeria.

Speaking to BusinessDay on the surge in flood cases across Lagos and other parts of the country, he stated, “Unregulated sand mining must be guided by an environmental impact assessment to prevent erosion and flooding. Also, the reclaiming of wetland areas should be stopped immediately to prevent flooding because wetlands are very important to our terrestrial environment.

“The wetland areas help retain water, thereby preventing flooding. But when, as a result of unplanned development, we are encroaching wetland areas, there is going to be flooding. When we deforest swamps that retain water, there is going to be flooding, because water must find its way.”

He called for a multi-stakeholders approach, adding that, “It starts with citizen stewardship because what we do at the household level is contributing to the crisis. For the government, they must enforce laws and regulations that are intended to protect the environment. The private sector must adopt international best practices that would protect the environment.”

Experts warn that filling wetlands displaces water, exacerbating flooding in low-lying areas like Ikorodu and beyond. Wetlands once covered vast portions; their loss, from 43 percent to 49 percent in 1965 to under 5 to 15 percent by 2014 in some areas, heightens vulnerability in a flood-prone megacity already facing climate change impacts.

Govt. defends exercise

Gbolahan Oki, the permanent secretary of the Office of Urban Development defends the exercise as essential for public safety near power lines.

Oki claims extensive engagements over five years, with residents of Makoko Waterfront, agreeing initially.

“Those opposing are stubborn boys refusing to vacate. The law requires wider setbacks (up to 250 metres), but 100 metres was a concession. If any power line drops into the water, it is the government they will blame,” Oki explains.

He questions the waterfront’s condition, stating, “Is that how the waterfront of any country looks?”

The demolitions form part of urban regeneration for megacity status, similar to exercises in Oworonshoki, Mile 12, and Eti-Osa to enforce regulations.

As protests continue and lives hang in the balance, Makoko’s story raises profound questions: Can development justify such human and environmental cost?

Residents continue to plead for mercy, justice, and a place to call home, before more infants, elders, and dreams are swept away by the tide of progress.