Nigeria may be 10,661 kilometres away from the United States, while Venezuela sits just 4,501 kilometres from Washington’s shores. That distance tempts us to believe that what happens in Caracas is too remote to matter in Lagos or Abuja. Yet in today’s interconnected world, geography is not a shield. The recent US strike in Venezuela and the dramatic removal of Nicolás Maduro from power is not merely a Latin American story; it is a global event with implications that reach into Nigeria’s politics, economy, oil and gas trade, immigration patterns, drug trafficking networks, and security architecture.

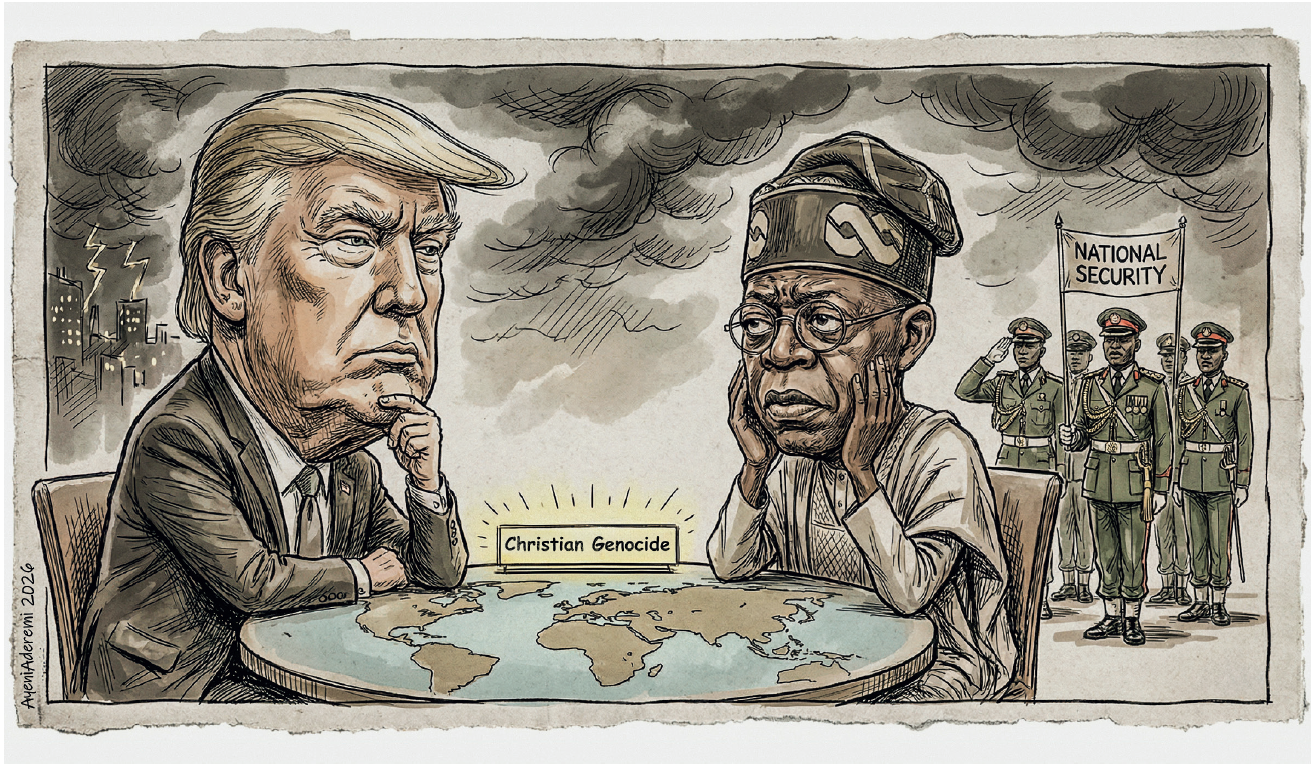

The first lesson for Nigeria is politics. The Venezuelan crisis demonstrates Washington’s willingness to intervene directly in the affairs of resource-rich states when it perceives instability or threats to American interests. For Nigeria, this sets a precedent that cannot be ignored. The Nigerian political class must recognise that sovereignty is increasingly conditional in a world where oil wealth and strategic geography attract external attention. The Venezuelan episode underscores the importance of strengthening democratic institutions, reducing corruption, and ensuring political stability. If Nigeria is perceived as fragile or mismanaged, it risks being drawn into the same vortex of external influence that engulfed Venezuela.

Economically, the implications are even more pronounced. Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, estimated at 303 billion barrels. With Maduro removed and US companies like Chevron poised to re-enter the Venezuelan oil sector, global supply dynamics are set to shift. Nigeria, whose economy remains heavily dependent on crude oil exports, must brace for the consequences. The Nigerian government has benchmarked its 2026 budget at $64.85 per barrel, but analysts warn that Donald Trump’s push for lower oil prices — possibly around $50 per barrel — could create a fiscal hole of over $10 billion. Such a shock would destabilise public finances, undermine infrastructure projects, and intensify pressure on the naira. The Venezuelan crisis is therefore not a distant drama but a direct threat to Nigeria’s fiscal stability.

Beyond the numbers, the oil and gas business faces new competition. A revived Venezuelan oil industry, backed by American capital and technology, could flood global markets with cheaper crude. Nigeria’s competitive edge would erode, particularly in markets where both countries compete for buyers. This reality makes diversification not just desirable but urgent. Agriculture, manufacturing, and technology must be scaled up to reduce dependence on oil revenues. The Venezuelan crisis is a reminder that Nigeria’s economic future cannot be tied indefinitely to the volatility of global crude markets.

Immigration is another dimension where lessons abound. Venezuela’s collapse prompted one of the largest migration crises in Latin America, with millions fleeing to neighbouring countries. Nigeria, already grappling with high youth unemployment and limited opportunities, could face similar pressures if oil revenues shrink and insecurity worsens. Economic instability often accelerates emigration, particularly of skilled professionals, intensifying the brain drain that already undermines Nigeria’s development. The Venezuelan experience warns us that when a resource-dependent economy collapses, migration becomes not just an option but a necessity for millions. Nigeria must therefore invest in job creation and social safety nets to prevent a similar exodus.

The crisis also has implications for transnational crime, particularly drug trafficking. Venezuela has long been a hub for narcotics routes into North America and Europe. Instability there could redirect drug flows through West Africa, with Nigeria as a key transit point. Already, Nigerian authorities struggle with porous borders and organised crime networks. A weakened Latin American enforcement environment could embolden traffickers to expand operations in West Africa, worsening Nigeria’s drug problem and stretching law enforcement capacity. The Venezuelan crisis is thus a warning that global criminal networks adapt quickly to geopolitical shifts, and Nigeria must be prepared to counter them.

Security, perhaps more than any other sector, stands to be affected. Lower oil revenues could reignite militancy in the Niger Delta, where communities depend on oil revenue and feel marginalised by the state. A fiscal squeeze would also constrain Nigeria’s ability to fund counter-terrorism operations against Boko Haram and ISWAP in the Northeast. The Venezuelan crisis illustrates how quickly instability in a resource-rich state can spiral into violence, displacement, and regional insecurity. Nigeria must therefore strengthen its security architecture, not only to protect its borders but also to ensure that economic shocks do not translate into armed conflict.

Taken together, these implications paint a sobering picture. Nigeria cannot afford complacency. The Venezuelan crisis is a reminder that oil wealth attracts geopolitical contestation, and that economic dependence on crude is a strategic vulnerability. As Donald Trump signals a “second, bigger wave” of interventions, Nigeria must prepare for shocks in oil markets, strengthen political institutions, and diversify its economy. The lesson is clear: distance may lull us into false security, but in a globalised world, 10,661 kilometres is no protection from the tremors of Washington’s next strike.

For Nigeria, the Venezuelan episode is not a foreign affair to be observed from afar. It is a mirror reflecting our own vulnerabilities and a warning of what could happen if we fail to act. The challenge is to learn from Venezuela’s collapse and to build resilience before the next strike comes — not just from Washington, but from the hard realities of global politics and economics.