In Nigeria, few social rituals are as predictable as the wave of prophecies that accompanies each new year. From declarations about elections and economic fortunes to warnings of disasters, deaths and breakthroughs, prophetic pronouncements occupy a powerful space in public life. For a deeply religious society, they offer reassurance, moral framing and a sense of divine order amid uncertainty. Yet as the country grapples with inflation, insecurity and political volatility, a harder question is gaining traction: how reliable are these prophecies when subjected to basic empirical scrutiny?

The answer matters not just for theology, but for public trust, economic behaviour and the role of religious voices in civic discourse. Nigeria’s vibrant Pentecostal and charismatic movements have created a platform where pastoral authority is often intertwined with predictive pronouncements. High-profile prophets command vast audiences, with their prophecies broadcast globally, dissected on social media, and treated as serious news by mainstream outlets. This unique fusion of faith, media and commerce has effectively created a “prophecy industry”—one with tangible influence on national dialogue and individual decision-making.

Building a prophecy prediction accuracy index

To move the conversation beyond anecdotes and selective memory, it helps to adopt a simple analytical lens: a Prophecy Prediction Accuracy Index (PPAI). This framework compares publicly stated, time-bound prophetic claims with observable outcomes. It is not a theological judgment, but a credibility test—similar to how markets evaluate forecasts, policy guidance or investment advice. While prophetic language often carries symbolism and conditionality, repeated engagement with concrete political, economic and social events inevitably invites measurable evaluation.

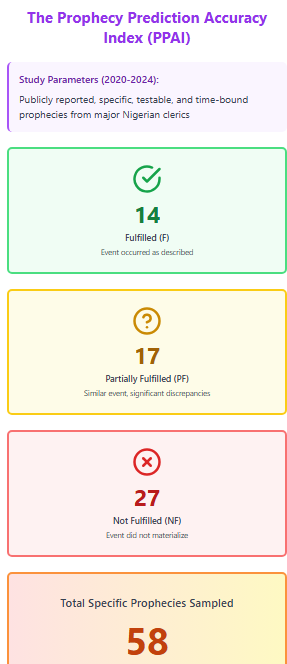

For this analysis, publicly reported prophecies from several major Nigerian clerics were examined over recent years (2020-2024), cataloguing only predictions that were specific, testable and time-bound. Sources included church New Year crossover service broadcasts, verified publications and major news reports. Each prophecy was scored as: Fulfilled (F) if the event occurred as described within the stated timeframe; Partially Fulfilled (PF) if an event of similar nature occurred but with significant discrepancies; or Not Fulfilled (NF) if the event did not materialise. The index is calculated as: (F + 0.5×PF) / Total Prophecies Sampled.

The data: hits, misses and strategic ambiguity

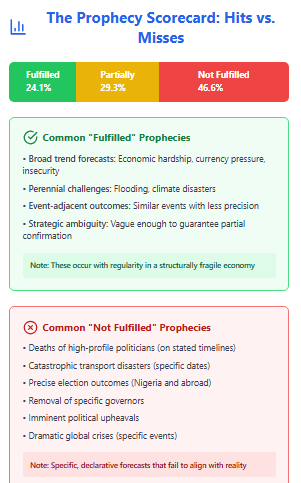

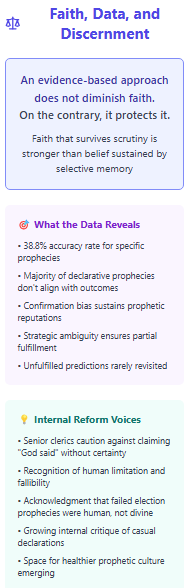

The review reveals a landscape of both notable validations and conspicuous failures. A significant share of high-profile predictions—especially those tied to elections, leadership changes, catastrophic events or global affairs—have not materialised as declared. Claims about imminent political upheavals, unexpected deaths of officeholders, dramatic global crises or decisive election outcomes frequently failed to align with reality within stated or implied timeframes. The list is substantial and specific: failed predictions of the deaths of high-profile politicians, catastrophic transport disasters on stated timelines, precise election outcomes in Nigeria and abroad, and the removal of specific governors. These misses are rarely revisited publicly, fading quietly as attention shifts to the next prophetic cycle.

At the same time, a smaller subset of predictions is often cited as fulfilled. These tend to fall into two categories. The first involves broad trend forecasts—economic hardship, currency pressure, insecurity or climate-related disasters—that occur with some regularity in a structurally fragile economy. The second involves event-adjacent outcomes, where something similar to a prediction occurs, though often with less precision or different causality than initially implied. Post-facto linkage of vague predictions to specific events (such as an illness of a public figure or a corporate merger) demonstrates the powerful role of confirmation bias in sustaining prophetic reputations.

When these patterns are quantified, the results are sobering. Using a conservative sample of 58 publicly documented, specific and testable prophecies: Fulfilled (F): 14, Partially Fulfilled (PF): 17, Not Fulfilled (NF): 27, PPAI: (14 + [0.5 × 17]) / 58 = 22.5/58 ≈ 38.8%

Under a strict empirical metric, fewer than four in ten specific prophecies are fully accurate, with a significant portion vague enough to be retroactively argued as partially correct. Under a tighter standard—where outcomes must closely match the original claim—the accuracy ratio drops closer to 30 percent. Put simply, the majority of declarative prophecies do not align cleanly with observable outcomes.

The economics of prophecy: risk, reward and rationality

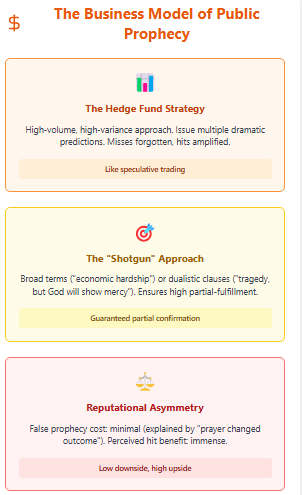

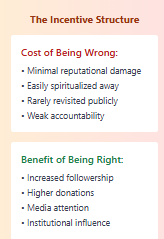

From an economic perspective, this pattern mirrors a familiar incentive structure. Prophetic forecasting often follows a high-volume, high-variance model. The business model reveals strategic rationality in three distinct forms.

The Hedge Fund Strategy: Multiple dramatic predictions are issued across political, social and economic domains. Misses are forgotten or spiritualised away, while hits are heavily amplified as proof of divine power, building brand equity and driving revenue. It is akin to speculative trading—scatter enough bets and celebrate the winners loudly.

The “Shotgun” Approach: Prophecies are couched in broad terms (“economic hardship,” “political unrest”) or dualistic clauses (“there will be a tragedy, but God will show mercy”). This ensures a high partial-fulfillment rate in a nation guaranteed some form of annual turbulence. Economic strain, political tension, security incidents and social unrest are persistent features of Nigeria’s landscape. Predicting turbulence in such an environment is less foresight than probabilistic inevitability.

Reputational Asymmetry: The cost of a false prophecy is minimal—often explained away by prayer, mercy or changed outcomes. The benefit of a perceived hit, however, is immense: increased followership, donations, media attention and institutional influence. The payoff structure is asymmetric: low downside, high upside. In market terms, this is a strategy with weak accountability but strong branding returns.

Confirmation bias ensures that vague accuracy is remembered, while specific failures are rationalised or forgotten. The result is an industry where ambiguity reigns and selective memory sustains reputations.

The social impact and eroding trust

The consequences extend beyond statistical curiosity. Prophecies intersect with financial behaviour, political sentiment and personal decision-making. Unfounded predictions can fuel panic, distort investment choices, heighten political tension or undermine confidence in democratic processes. False prophecies can incite unnecessary anxiety, distort financial and electoral decisions, and ultimately erode trust in religious institutions. This erosion is acknowledged from within.

Senior clerics have publicly cautioned against claiming “God said” without certainty, and theological commentators have attributed many failed election prophecies to human, rather than divine, origins. This internal critique suggests space for a healthier culture—one that distinguishes spiritual exhortation from speculative forecasting. Conversely, credible moral guidance and cautionary counsel can play a stabilising role. The problem is not prophecy per se, but the absence of accountability proportional to influence. When prophetic claims enter the public domain—predicting national elections, economic trends or security crises—they invite empirical evaluation. Their performance against reality shapes not only spiritual credibility but also social cohesion.

Faith, data and discernment

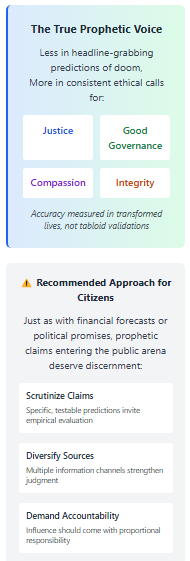

An evidence-based approach does not diminish faith. On the contrary, it protects it. Faith that survives scrutiny is stronger than belief sustained by selective memory. Just as citizens are advised to treat financial forecasts or political promises with caution, prophetic claims that enter the public arena deserve similar discernment. The Prophecy Prediction Accuracy Index of approximately 39% is not a verdict on spirituality, but a mirror held up to practice. This exercise is not to dismiss faith or the possibility of divine communication, but to advocate for analytical rigour in the public square. In a society hungry for hope and direction, the most valuable prophetic voice may not be the loudest predictor of events, but the most consistent advocate for integrity, compassion, justice and good governance. Those are outcomes whose accuracy is measured not by headlines, but by lived experience—and whose credibility compounds rather than decays.

At a time of national anxiety, Nigerians deserve clarity about which voices are rooted in discernible reality. The true prophetic voice, one might argue, is less in the headline-grabbing prediction of doom and more in the consistent, ethical call for justice, good governance and communal compassion—areas where accuracy is measured in transformed lives, not tabloid validations. A culture of accountability, where unfulfilled predictions are openly addressed, could strengthen both religious integrity and public trust.

As with financial advisories, citizens would do well to remember: past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results, and diversification of information sources remains the bedrock of sound judgment. Prophecy, like any influential public claim, must contend with credibility over time. And right now, credibility is in short supply.