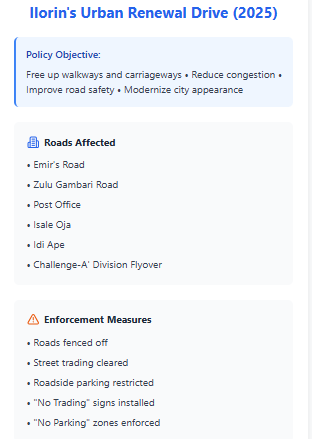

In 2025, the Kwara State Government set in motion a highly visible—and deeply contested—urban renewal drive in Ilorin. Major roads such as Emir’s Road, Zulu Gambari Road, Post Office, Isale Oja and Idi Ape were fenced off or cleared of street trading and roadside parking. The aim, according to government officials, was straightforward: free up walkways and carriageways, reduce congestion, improve road safety and give the city a cleaner, more organised look. Around flashpoints like the Challenge-A’ Division Flyover, “No Trading” and “No Parking” signs now signal a tougher stance on how public space is used. From the government’s perspective, these measures are about modernising Ilorin—upgrading infrastructure, protecting commuters and steering the city toward a more orderly model of urban growth.

Traders’ plight and economic exposure

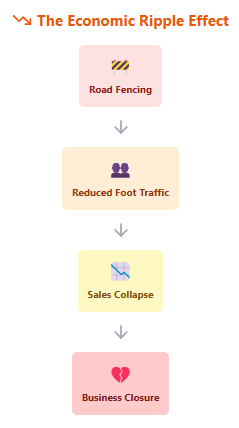

For traders who have built their livelihoods around busy roads and constant traffic, however, the change has been jarring. In areas like Post Office and Challenge—once buzzing commercial zones—many small vendors say sales have fallen sharply. Hundreds have protested, some holding placards declaring that the barricades have effectively “killed” their businesses. Their argument is simple: visibility matters. When customers can no longer easily see or access their stalls, impulse buying disappears and daily turnover collapses. For traders operating on thin margins, with little savings to fall back on, prolonged disruption can quickly become existential. In an economy already strained by high inflation and limited formal job opportunities, the fear is that these policies could push many informal businesses over the edge, deepening unemployment and household hardship.

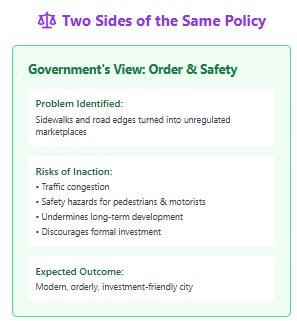

The urban renewal rationale: Order over disorder

From a policy lens, the government’s position reflects a familiar dilemma in Nigerian cities. Over time, sidewalks and road edges often turn into extensions of the marketplace—filled with traders, informal motor parks and improvised stalls. While this fuels economic activity, it also clogs traffic and creates real safety risks for pedestrians and motorists. Urban planners and lawmakers have long argued that unregulated street trading undermines long-term development and discourages investment. Calls for modern markets and clearer land-use rules are rooted in the belief that cities function better when public spaces are predictable and well managed. In that sense, fencing roads and reclaiming setbacks fits neatly into a broader push for order, efficiency and a cityscape that can attract investment and improve overall quality of life.

Weighing costs: Lost sales and social strain

Still, the economic and social costs are hard to ignore. Many informal traders depend almost entirely on passing traffic to generate sales. Once that flow is cut off, footfall drops, incomes shrink and informal credit arrangements begin to unravel. For a sector that acts as a buffer for the unemployed and underemployed, losing access to prime trading spots can quickly translate into rising vulnerability.

Tensions have already flared in places like the Challenge market, with clashes reported between traders and enforcement teams. Political actors have also entered the debate, describing the measures as economic suffocation. Beneath the rhetoric lies a basic truth: in cities like Ilorin, access and mobility are tightly linked to market vitality.

Two sides of a complex policy choice

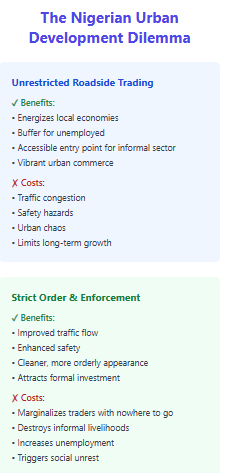

Ilorin’s situation offers no neat answers. Unrestricted roadside trading can energise local economies, but it also brings congestion, safety hazards and urban chaos that limit long-term growth. Yet policies that focus solely on order and traffic flow risk marginalising traders who have nowhere else to go. Urban renewal, if it is to be sustainable, cannot end with fences and enforcement alone. It has to include clear pathways for traders to move into approved, well-designed commercial spaces that preserve both livelihoods and urban functionality.

A path forward: Balance and inclusion

The lesson from Ilorin is one Nigerian cities cannot afford to miss: urban renewal works best when it is paired with economic inclusion. Investing in safer roads and cleaner streets is important, but so is protecting the livelihoods that depend on urban commerce.

That means expanding and modernising markets, improving access rather than restricting it, and creating policies that help informal traders transition into the formal economy. Above all, it requires honest dialogue between government and those affected. Cities do not thrive on concrete and fences alone. They thrive on economic activity, opportunity and the confidence that progress will not come at the cost of people’s livelihoods.