Insecurity has long been the country’s most stubborn challenge; it is a problem that has outlived successive administrations and continues to shape the daily lives of millions. Banditry, kidnapping, and terrorism have left communities devastated, economies disrupted, and citizens disillusioned with their government’s inability to protect them. While repeated promises have been made by successive governments to confront this menace, the persistence of such threats has fuelled suspicion that capacity is not the real obstacle but an absence of genuine political will. The entrenched belief in the complicity of powerful elites and politicians in sustaining insecurity – or unwillingness to confront those who profit from it – has gained traction.

President Bola Tinubu’s recent declaration of a state of emergency on security has revived debate about what political will should look like in practice. Nigerians have heard similar pronouncements before, but the reality on the ground has remained unchanged. Political will must be more than speeches; it must translate into actions that disrupt the networks of crime and terror, even when those networks traverse political or economic interests. It requires a government prepared to face uncomfortable truths, including the possibility that some of its own allies and cabinet members may be involved.

For years, allegations have circulated that sponsors of terrorism and banditry include people in influential positions. Naming and prosecuting such sponsors would, of course, send a strong signal that no one is above the law. The anonymity of perpetrators and sponsors has become a shield for impunity, but political will must pierce that shield by exposing those behind the violence and holding them accountable. Otherwise, insecurity will continue to be a profitable business for elements that thrive in chaos.

Conspiracy theories of elite involvement in insecurity reflect a deeper crisis of confidence. Whether they are true or not, they thrive because the government has failed to act decisively.

The recent ‘resignation’ of the defence minister Mohammed Badaru Abubakar and the immediate appointment of General Christopher Musa, immediate past Chief of Defence Staff in his place, has been interpreted by some as a sign that the administration is willing to jig the security architecture. Musa’s appointment is being watched closely as a test of whether leadership changes at the top can translate into more effective strategies on the ground. To many, the move is symbolic of political will – a readiness to remove those officials who have failed to deliver and replace them with figures believed to have both the expertise and resolve to take on insecurity. Whether this change would yield tangible results remains to be seen; it does appear to signal at least a recognition that fresh approaches are required.

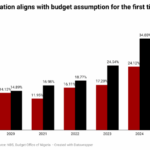

Equally essential is funding and institutional reform. Most often, the security agencies in Nigeria have been poorly funded and equipped, bedevilled by corruption, with the defence fund growing ‘wings’. Political will must include the courage to reform institutions that have become compromised. This may mean sacking officials who have failed to deliver, restructuring agencies that are bloated but ineffective, and investing in modern technology for intelligence gathering. Oversight mechanisms need to be strengthened to block funds from being siphoned off by corrupt generals.

Foreign involvement is another issue on which opinions are divided. Some say Nigeria should seek international assistance in intelligence, training, funding, or outright military action. Others believe outsourcing security undermines sovereignty. There can be a balanced approach wherein Nigeria’s own efforts are strengthened through foreign partnerships that enhance capacity in intelligence gathering, collaborating on border security, and learning from countries which have successfully reduced terrorism.

As for the judiciary, delays in the prosecution of perpetrators and sponsors have often allowed suspects to escape justice or re-enter society without consequence. The political will must ensure that courts are empowered to handle terrorism and banditry cases efficiently, since this only serves to perpetuate cycles of violence and breeds a lack of trust in government action.

Political will by the government will convince citizens that their leaders are acting in their interest. This requires consistent communication and not propaganda. Communities affected by violence need to be assured of tangible improvement in the safety of lives and property. Political will must be shown not only in Abuja but also in villages and towns where insecurity surfaces daily. When farmers can return to their farms without fear, children can go to school without the threat of abduction, and travellers can move on highways without dread, then the government’s commitment will be clear. Until then, declarations will remain empty.

The insecurity problems of Nigeria are not insurmountable. Many nations have faced similar challenges and emerged much stronger. What differentiates success from failure is leaders’ preference to confront roots of violence rather than its symptoms. This, for Nigeria, means addressing corruption, revealing the sponsors, reforming institutions, and an investment in communities. It means refusing to allow insecurity to be normal. Above all, it means demonstrating through action that the safety of citizens is non-negotiable. The political will to curb insecurity in Nigeria has to be uncompromising; the kind that can take on elites, reform institutions, and wear the robe of accountability. It needs to appreciate that insecurity is not only a military issue but a political and social one. Declaring a state of emergency is only the first step, for which it takes courage, transparency, and persistence to sustain the fight. Nigerians have waited for far too long to have a government that matches words with actions. If political will is finally summoned in its true form, then insecurity can be curbed, and the nation can begin to heal from years of violence. Without it, the cycle will continue, and the promise of peace will remain elusive.