Nigeria’s urban water crisis is no longer just a public-service failure. It has become one of the country’s most persistent and undercapitalised infrastructure markets.

Across fast-growing cities and industrial corridors, demand for treated water and regulated sanitation is rising rapidly while public supply remains structurally weak. The widening gap between demand and supply is quietly opening a durable investment opportunity.

Urban demand expands as public supply stagnates

Nigeria’s population has crossed 227 million, according to national demographic estimates, with urbanisation growing at more than 4 percent annually. Lagos alone absorbs hundreds of thousands of new residents every year.

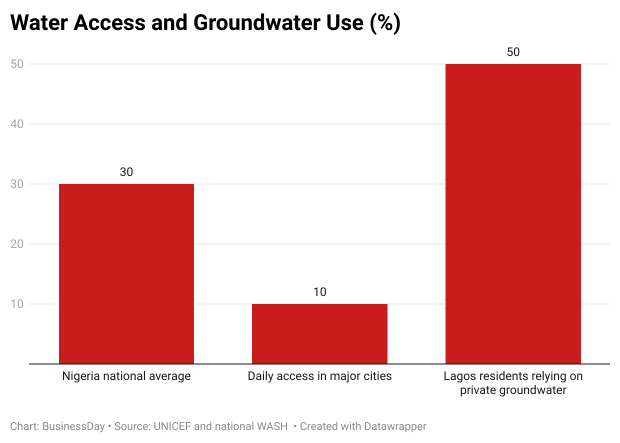

Yet fewer than 30 percent of Nigerians have access to safely managed drinking water, according to UNICEF and national WASH data. In many major cities, daily access to public pipe-borne water is below 10 percent of households.

State water agencies operate with ageing infrastructure, low tariffs that do not cover operating costs, and chronic capital underinvestment. In Lagos, installed public treatment capacity runs into hundreds of millions of gallons per day, but effective output delivered to households remains far lower due to power shortages, network losses and illegal connections.

According to sector studies, more than half of Lagos residents now depend on private groundwater sources such as boreholes and wells.

The private water economy already clears in cash

This structural failure of public supply has given rise to a large private water economy that already clears in cash. In Lagos alone, tanker water is estimated to serve several million residents daily.

Retail tanker prices typically range between N6,000 and N12,000 per 10,000 litres depending on season and distance. For households consuming between 15,000 and 20,000 litres monthly, annual water spending can exceed N150,000.

Across commercial estates, hospitals, factories and industrial users, expenditure is significantly higher and often contractual.

Sachet and bottled water production forms another high-volume segment. Nigeria is widely regarded as one of the world’s largest sachet water markets, driven by unreliable household supply and rising health concerns, according to industry surveys.

The implication for investors is straightforward: Nigerians already pay for water every day, only through fragmented and inefficient delivery systems.

Where the institutional investment gap lies

The main institutional investment gap does not lie in retail sachet water. It lies in bulk water production, treatment, storage and contracted distribution to estates, industrial parks, hospitals, schools, logistics hubs and commercial districts. These customers demand reliability and are increasingly willing to sign multi-year supply contracts with tariff indexation.

Integrated platforms that combine borehole fields, modular treatment plants, bulk reservoirs and tanker fleets convert an informal trade into a utility-style infrastructure asset. With contract tenors typically ranging from three to ten years, such platforms can move from daily cash transactions to predictable project-finance cash flows.

Sanitation and wastewater deepen the revenue base

Nigeria’s sanitation gap is as large as its water deficit. According to national sanitation surveys, more than 70 percent of households rely on septic systems, while organised sewage treatment remains confined to a handful of districts nationwide. Environmental regulators are now enforcing mandatory desludging and effluent treatment for estates, hotels, factories and hospitals.

Certified waste evacuation now costs large commercial users hundreds of thousands of naira per month, turning sanitation into a recurring compliance-driven expense rather than an occasional service. Investors who combine water supply with wastewater management gain a dual-revenue infrastructure profile that is both defensively positioned and regulation-backed.

Why macroeconomic stress strengthens the investment case

Macroeconomic stress is strengthening rather than weakening the investment case. Water demand does not decline in recessions. Inflation raises tariffs but does not materially reduce consumption. FX volatility raises the cost of imported pumping and treatment equipment, but it also increases the replacement value of existing operational assets. Hybrid solar-diesel systems now allow operators to limit exposure to grid failures and rising diesel costs.

Unlike consumer discretionary sectors, water infrastructure benefits when urban density rises and climate volatility intensifies. Flooding, rainfall instability and groundwater contamination are increasing the premium placed on professionally managed water and sanitation systems.

Geographic markets with strongest commercial potential

The geographic markets with the strongest commercial potential remain Lagos metropolitan districts such as Lekki, Ajah, Ibeju-Lekki, Ikoyi, Ikeja and Agege, where residential density and commercial activity intersect with minimal public water coverage.

Ogun State’s industrial belt around Ota, Agbara and Sagamu continues to show strong bulk-water demand from factories and logistics operators. In Rivers State, the Port Harcourt–Eleme corridor supports industrial and oil-services demand, while Abuja’s satellite towns including Kubwa, Lugbe and Gwarimpa remain heavily dependent on private water supply.

Sensitivity to pricing, power and utilisation

Project economics are most sensitive to three variables: utilisation rate, power cost and transport distance. According to infrastructure cost models, a 10 percent increase in capacity utilisation often produces more than a proportional rise in net operating margins because fixed costs are front-loaded.

Power typically accounts for 15 to 25 percent of operating expenses. A 20 percent reduction in energy cost through solar deployment materially lifts cash-flow stability. Transport distance directly affects fuel cost per cubic metre of delivered water, making proximity to customer clusters critical.

Primary risks that investors must manage

Primary risks that investors must manage include uneven regulation across states, particularly around tariff approvals and groundwater licensing. Land acquisition for reservoirs and treatment sites remains slow in many urban areas.

Groundwater contamination risk requires continuous monitoring. Payment delays occur where public institutions are counterparties. FX exposure on imported equipment can distort capital budgets if not properly hedged.

Why the opportunity remains structurally attractive

Despite these risks, demand risk is almost non-existent. Nigeria already operates a massive private water economy outside formal balance sheets. Urbanisation, industrial expansion, climate stress and sanitation enforcement are all moving in the same direction. The constraint is not willingness to pay. It is the absence of scaled, professionally financed infrastructure.

For long-term capital, water and sanitation offer an uncommon combination of real-asset security, inflation-linked pricing, daily cash generation and weak correlation with equity and fixed-income markets. Nigeria’s cities already function because private operators supply water and evacuate waste. The next phase is the formalisation of those services into investable infrastructure portfolios.