More than a decade has passed since the abduction of nearly 300 girls from their school in Chibok, Borno State, a moment that jolted the world and forced Nigeria to confront the dangers facing its learners. That tragedy gave rise to the Safe Schools Initiative, a pledge to strengthen classroom security and reassure families that education would not come at the risk of their children’s lives.

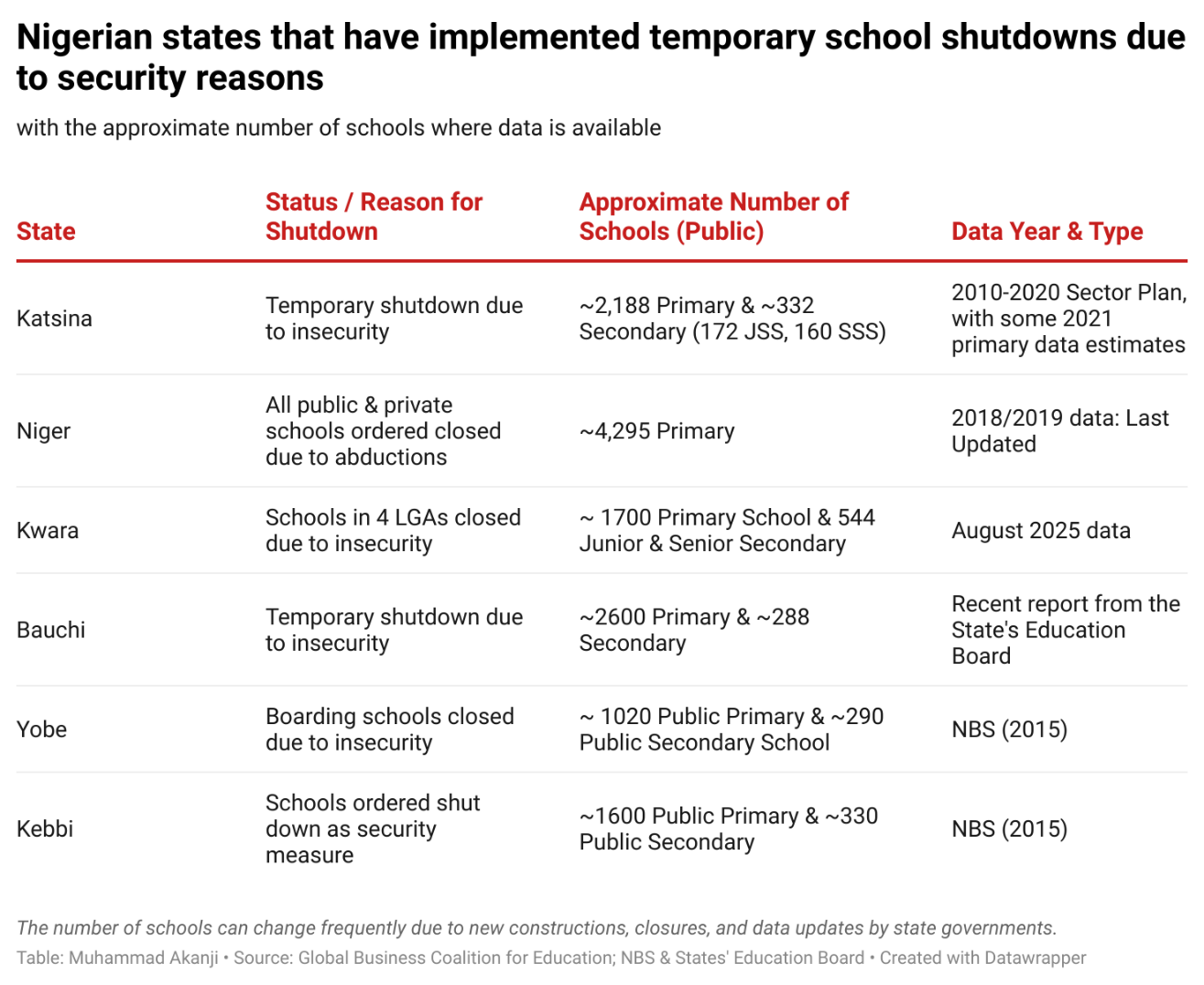

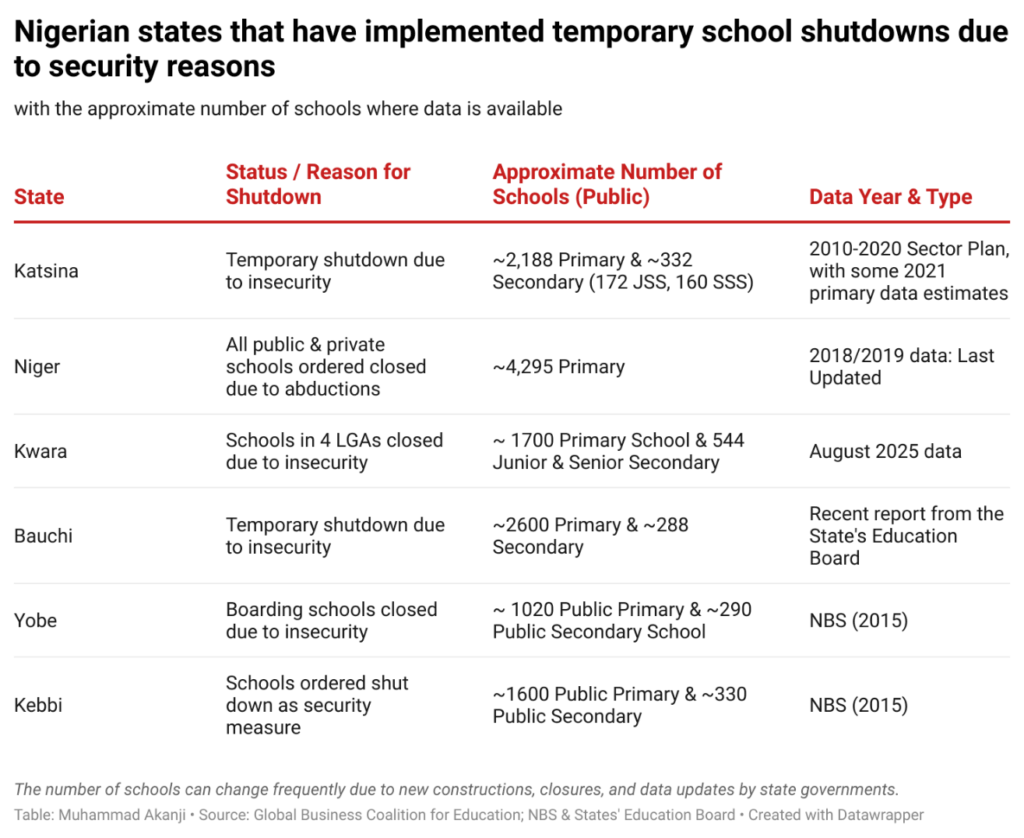

Eleven years later, the nightmare hasn’t ended. The November 2025 attack in Papiri, Niger State, where over 300 students and teachers were taken, continues to echo across the country. Kuriga in Kaduna faced its own heartbreaking episode in 2024, and the abduction of schoolgirls from the Government Girls’ School in Maga Town, Kebbi, added to the mounting unease in communities already on edge.

Recent data show that only about 37% of schools in 10 high-risk states have basic early-warning systems, and just 14% meet safe-infrastructure standards. For many parents, these numbers raise a difficult question: how secure are the places meant to shape their children’s future?

Meanwhile, the country’s school-security budget: a once-promising ₦144.7 billion plan for 2023-2026 remains largely unspent or perhaps unaccounted for. When the Safe School Initiative (SSI) was launched in 2014 with a $30 million fund and global praise, it was billed as the turning point that would finally protect Nigerian children from terror. Eleven years later, the gap between promise and protection remains obvious.

The SSI’s Mandate

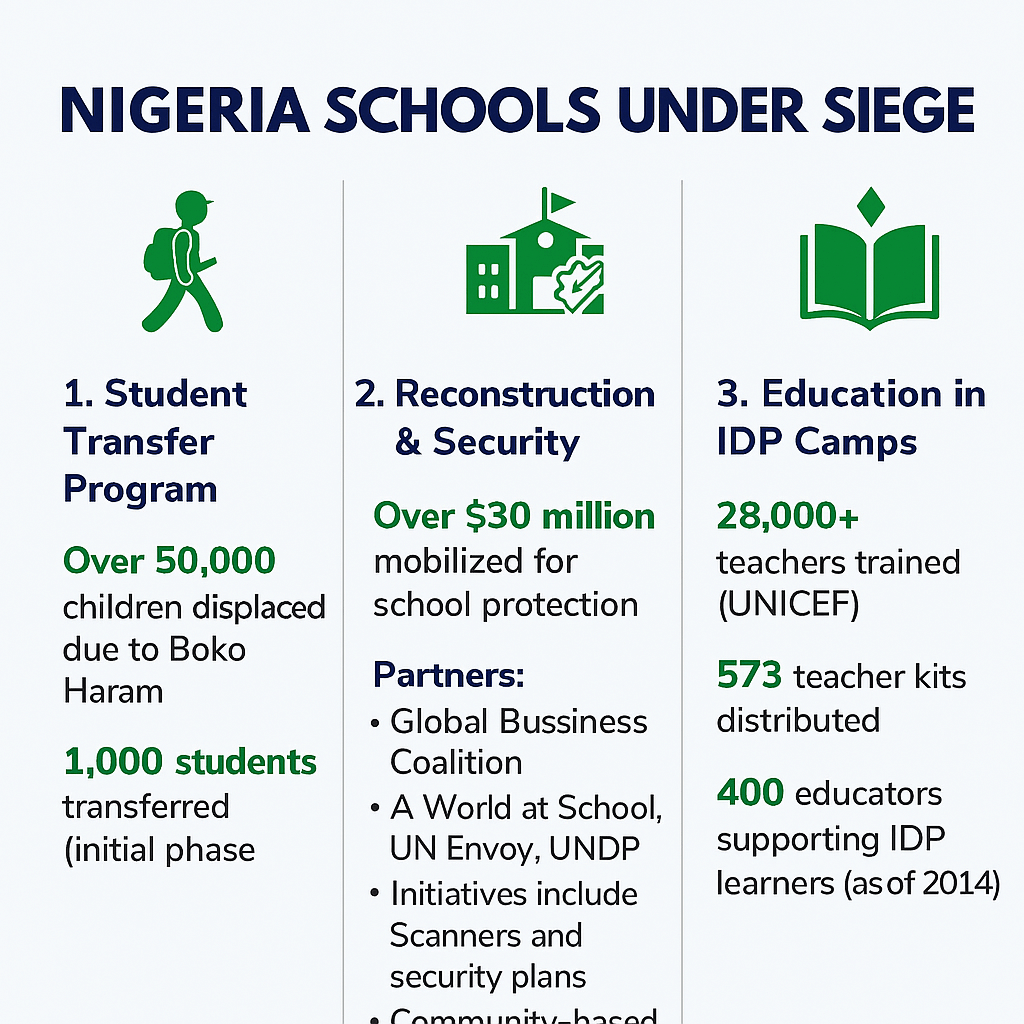

An initial investment from the Global Business Coalition for Education, supported by World at School and the UN Special Envoy for Education, allowed the SSI to raise over $30 million to protect schools in Nigeria. The effort started in the Northeast and expanded nationwide in 2023. Managed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) through a multi-donor trust fund, the initiative received international backing from the United States, the United Kingdom, Norway, Germany, and the African Development Bank (AfDB).

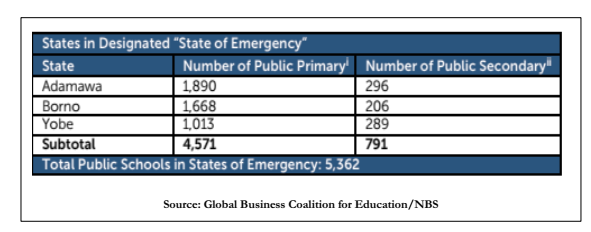

As of then, nearly 50000 children displaced from their homes by Boko Haram were helped by the initiative through interventions like the Student Transfer Programme to transfer those students in the highest risk areas to schools in safer parts of the country. For example, the students from high-risk areas in three states of emergency are transferred to one of 43 federal community colleges. The program began with 2400 students, 800 from each state, with about 5000 students transferred in the first 12 months of the programme.

A school rebuilding programme was rolled out to strengthen physical security in institutions identified as high-risk under the SSI framework. This included upgrading infrastructure, implementing structured security plans, and introducing additional measures, such as scanners and solar power, where gaps were identified. Emergency response procedures were also developed for schools, while school-based management committees received support to function as first responders when incidents occur.

Support was also extended to children displaced by conflict, as new learning strategies and materials were introduced across several IDP camps. By the end of 2014, UNICEF and the Nigerian government had enrolled more than 28,000 children in a double-shift schooling system designed to manage overcrowding and keep learning continuous. Around 683 teachers received training for this setup, and roughly 35,000 school bags and learning materials, along with 400 school-in-a-box kits, were distributed to help displaced learners stay engaged in the classroom.

But despite the lofty initiative, more than 42,000 schools remain unprotected, lacking fencing, surveillance, or trained security personnel. As attacks spike in Kaduna, Zamfara, Niger, and Katsina, many schools shorten hours, relocate entirely, or shut their doors indefinitely.

This is the grim reality: in vast parts of Nigeria, education is no longer guaranteed- it is negotiated daily with danger.

The New Normal: Learning in a Landscape of Fear

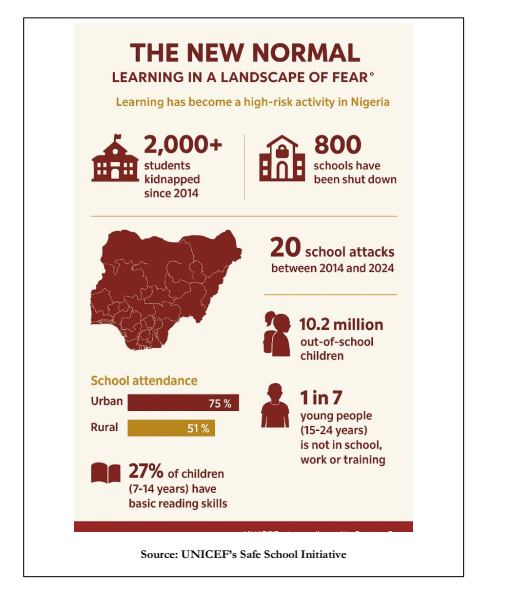

Across Nigeria, schooling has become a perilous activity, especially in the North (with North Central the new hotbed of insurgency and terrorism), where insecurity has turned classrooms into soft targets. Since Chibok in 2014, over 2,000 students have been kidnapped, according to UNICEF’s reports, and more than 800 schools have been shut down due to persistent attacks. Between 2014 and 2024 alone, about 20 major school attacks were recorded across 10 northern states; a pattern so entrenched that learning is now shaped by fear rather than curiosity.

The insecurity exacerbates an already fragile education system. Nigeria has 10.2 million out-of-school children, the highest in the world, and ongoing insecurity pushes this number higher each year. Urban school attendance is at 75%, but it drops to 51% in rural areas where most attacks happen. Among the poorest households, attendance is only 53%, compared to 83% for the wealthiest, widening the inequality gap.

Learning outcomes are deteriorating too: only 27% of children (ages 7–14) have basic reading skills, and 25% have foundational numeracy skills. Meanwhile, 1 in 7 Nigerian youths (15–24 years) is neither in school nor employed: a pipeline of vulnerability that insecurity continues to feed.

States were expected to co-fund security upgrades, yet multiple audits and investigative reports reveal diverted, delayed, or untraceable SSI allocations, leaving many communities with nothing more than freshly painted signboards branding schools as “safe.” In numerous LGAs across Borno, Kaduna, Niger, and Zamfara, “secured” schools rely not on federal or police presence but on local vigilantes armed with torchlights and dane guns; a symbolic shield against coordinated bandit raids.

The illusion becomes more troubling when juxtaposed with escalating attacks since 2014, underscoring how minimal the impact of SSI has been on real security outcomes. The programme may exist on paper, but on the ground, safety remains a negotiation between fear, luck, and community improvisation.

Are We Securing Classrooms or Surrendering to Terrorists?

Nigeria’s growing reliance on fences, gates, and ad-hoc guards raises a troubling question: are we protecting schools, or quietly retreating from them? Each year, states in the North shut classrooms during peak attack seasons, effectively conceding territory to armed groups. Enrolment is collapsing: Kaduna has seen a 22% decline, and some LGAs in Zamfara report drops of 30%, as parents refuse to risk their children’s lives. Meanwhile, bandits have shifted from road attacks to mass school abductions, exploiting ransom incentives. Fortification without reclaiming territory signals not strength, but a slow, painful surrender; one school at a time.

Here’s the hard truth: from Chibok to Maga Town, Nigeria’s safest school remains a myth, while violence, fear, and closures continue to deprive millions of their education. The question now isn’t when schools will be safe but whether children will ever learn in peace again.

Reclaiming the Schools

To truly secure Nigerian schools, safety must shift from defensive walls to proactive protection. First, rapid-response security squads should be deployed around school clusters to cut response time during attacks.

Second, community intelligence networks and early-warning systems must be formalised to detect threats before they materialise.

Third, school security funding requires transparent, ring-fenced budgeting to prevent diversion.

Finally, absolute protection depends on coordinated operations among the critical stakeholders, police, NSCDC, and vetted state vigilante groups. Only a holistic, multi-layered security ecosystem, not fear-driven fortification like that in Niger State, can reclaim the classroom and restore learning as a safe public good.