Nigeria’s official jobless rate looks enviably low. The reality is alarmingly different…

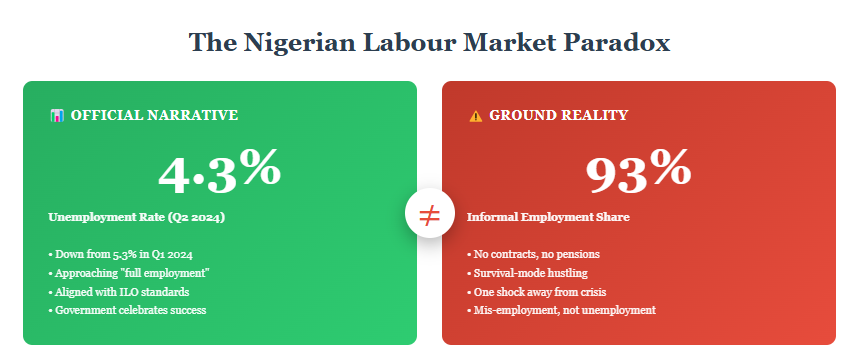

When the National Bureau of Statistics announced that Nigeria’s unemployment rate had fallen to 4.3% in the second quarter of 2024—down from 5.3% in Q1—the government could be forgiven a moment of self-congratulation. After years of subsidy reforms, currency devaluation, and painful fiscal tightening, here at last was vindication: Africa’s most populous economy was approaching what economists call “full employment.” There was only one problem. Nobody believed it. Not the graduate hawking phone accessories in Lagos traffic. Not the agricultural economist who counted anyone working an hour a week as “employed.”

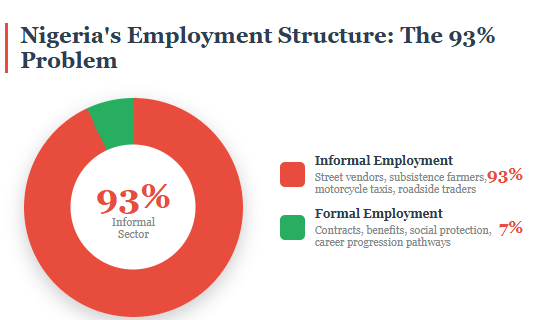

And certainly not the 93% of Nigeria’s workforce trapped in what polite statisticians call “informal employment”—a euphemism for survival-mode hustling with no contracts, no pensions, and no pathway to prosperity. Nigeria does not have an unemployment crisis. It has something far more insidious: a mis-employment crisis dressed up in the statistical clothing of success.

The methodology that changed everything

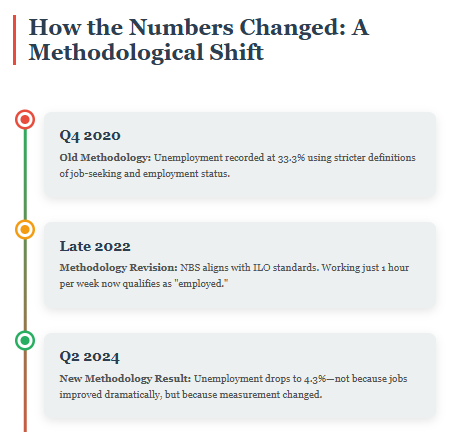

To understand how Nigeria arrived at this paradox, one must first understand what changed. In late 2022, the NBS aligned its labour-force methodology with International Labour Organization guidelines. The previous definition—which recorded a catastrophic 33.3% unemployment in Q4 2020—was scrapped.

Under the new framework, anyone who worked for at least one hour during the survey week counts as employed. This is not statistical chicanery. The revision brings Nigeria into line with global standards, making cross-country comparisons more meaningful. But applying a universal metric to an economy where 93% of jobs are informal creates what might charitably be called a measurement problem—or, less charitably, an illusion.

Consider what “employment” now captures: the woman selling roasted plantain from a roadside stall, the motorcycle taxi driver dodging potholes for ₦500 fares, the subsistence farmer whose entire productive capacity is defeated by a single dry season. All employed.

All contributing to that enviable 4.3%. All one medical emergency away from destitution. This is the uncomfortable truth beneath Nigeria’s headline number: the unemployment rate has become disconnected from the employment quality that determines household welfare, tax revenue, productivity growth, and social stability. When nine in ten jobs offer neither security nor upward mobility, celebrating low unemployment becomes an exercise in self-deception.

What the disaggregated data actually shows

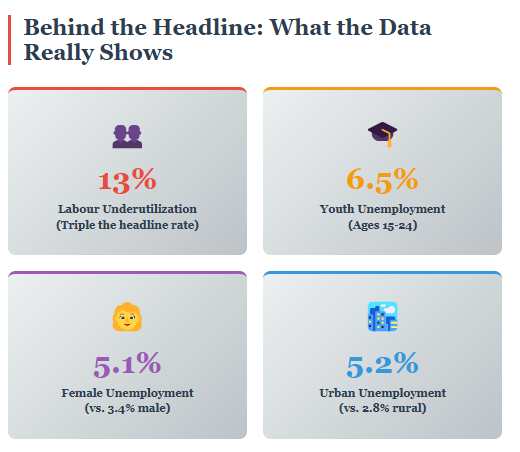

Peel back the headline figure and the labour market reveals its fault lines with uncomfortable clarity.

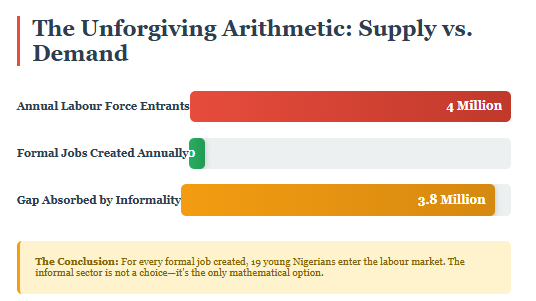

Youth unemployment stands at 6.5% for the 15-24 age cohort—hardly catastrophic on paper, but devastating when contextualized. Nigeria adds roughly 4 million young people to its labour force annually, yet formal sector job creation barely reaches 200,000. The arithmetic is unforgiving. Most school-leavers are not “unemployed” under official definitions—they are absorbed into informal micro-enterprises or agricultural subsistence, their human capital underutilized and their economic potential untapped.

Gender disparities persist with stubborn consistency. Female unemployment runs at 5.1% versus 3.4% for males, reflecting structural barriers that statistics alone cannot capture: cultural constraints on women’s mobility, unequal access to credit, the “second shift” of unpaid domestic labour that limits formal workforce participation. These are not statistical artefacts. They are policy failures.

Regional variations tell yet another story. Urban unemployment (5.2%) outpaces rural (2.8%), but this differential reflects labour market structure, not rural prosperity. Rural “employment” overwhelmingly means smallholder farming and informal trade—activities that keep people nominally busy while leaving them economically vulnerable. The lower rural unemployment rate is not evidence of thriving job markets; it is evidence of fewer alternatives to marginal livelihoods.

Perhaps most revealing is the labour underutilization rate—a metric combining unemployment with time-related underemployment. This stood at 13% in Q2 2024, triple the headline unemployment figure. These are Nigerians working fewer hours than they desire, earning insufficient income, seeking additional employment but classified as “employed” because they exceed the one-hour threshold. They are statistically invisible yet economically real.

Why Nigeria cannot create decent jobs at scale

The structural impediments are well-documented, if inadequately addressed.Demographics and dependency. Nigeria’s population growth (2.5% annually) outstrips economic expansion (3-4% GDP growth), creating a labour-supply tsunami that formal sector demand cannot absorb. With a median age of 18, the country should be reaping a demographic dividend. Instead, it risks a demographic disaster—millions of young people trapped in low-productivity informality or, worse, economically inactive and socially alienated.

Infrastructure deficit. Businesses that generate quality employment require reliable power, functional logistics, and predictable operating environments. Nigeria offers none of these at scale. Manufacturers spend as much on diesel generators as on labour. Logistics costs consume 30-40% of production expenses. Investors price in political risk and policy volatility. The result: capital goes elsewhere, and with it, jobs.

Perverse incentives for informality. Why would a micro-entrepreneur formalize when doing so means navigating opaque taxation, multiple regulatory agencies, and unpredictable enforcement? The informal sector is not a choice; it is a rational response to a hostile formal business environment. Until formalization offers tangible benefits—access to credit, contract enforceability, market opportunities—entrepreneurs will rationally remain invisible to statisticians and tax collectors alike.

Skills mismatch and education decay. Nigeria produces 500,000 university graduates annually, many of whom studied curricula designed decades ago for an economy that no longer exists. Meanwhile, employers complain of skill shortages in digital literacy, technical trades, and applied sciences. The education system prepares young people for government jobs that disappeared in the 1980s, not for the knowledge economy of the 21st century.

What governments have tried—and why it has not worked

To its credit, the federal government has not been idle. The N-Power scheme temporarily employed hundreds of thousands of graduates. States like Edo launched “EdoJobs” initiatives. The Central Bank deployed targeted lending to agriculture and manufacturing. Development partners offered technical assistance and concessional financing.

Yet these interventions share common shortcomings: they treat symptoms, not causes. N-Power provides stipends, not skills. CBN lending schemes reach few businesses due to collateral requirements and interest rate structures.

State programmes scale modestly before political cycles reset priorities. More fundamentally, these are supply-side interventions in a demand-constrained environment. You cannot skill-train your way out of an economy that creates 200,000 formal jobs for 4 million labour-force entrants.

You cannot entrepreneurship-programme your way past infrastructure collapse and macroeconomic volatility. The binding constraint is not worker capability; it is the absence of an enabling environment for labour-absorbing growth.

A realistic path forward

Fixing Nigeria’s labour market requires confronting uncomfortable truths and making politically difficult choices.

First, redefine success. Stop celebrating the 4.3% unemployment rate as an achievement. Adopt labour-market indicators that capture informality, underemployment, and job quality. Set national targets not for unemployment reduction but for formal employment growth—measurable, ambitious, and transparently reported.

Second, declare war on the business environment. Nigeria ranks 131st out of 190 on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index. This is not acceptable for a country aspiring to middle-income status. Streamline business registration to 48 hours. Digitize all regulatory interfaces. Impose strict timelines on permit issuance. Publish scorecards naming and shaming non-compliant agencies. Make life easy for job-creators, and jobs will follow.

Third, fix power. This is the single highest-return intervention available. Stable electricity would unlock manufacturing, formalize service enterprises, and increase productivity across sectors. Whether through privatization, public investment, or hybrid models, Nigeria must solve its electricity crisis as if national survival depends on it—because increasingly, it does.

Fourth, formalize informality. Design a tax regime specifically for micro-enterprises: simplified, digital, proportional to revenue, and bundled with tangible benefits (access to government contracts, credit, business development services). Make formalization attractive, not punitive. The 93% informal workforce represents untapped tax base, unprotected workers, and unmeasured economic activity. Integrate them, don’t alienate them.

Fifth, align education with economic reality. Mandate curriculum reviews every five years with private-sector input. Expand vocational and technical training. Incentivize universities to measure graduate employability, not just enrollment. Treat education as economic infrastructure, not social welfare.

Sixth, empower women economically. Enforce equal-pay legislation. Subsidize childcare for working mothers. Expand women’s access to agricultural land and commercial credit. When women work productively, household incomes rise, children’s educational outcomes improve, and national GDP expands. Gender equity is not philanthropy; it is economic strategy.

The stakes could not be higher

Nigeria stands at a crossroads. Its youthful population could be the engine of prosperity—or the fuel for instability. The choice depends on whether policymakers confront the employment crisis with the urgency it demands. The 4.3% unemployment rate is not evidence of success. It is evidence of measurement inadequacy.

Behind that number are millions of Nigerians trapped in precarious livelihoods, their talents underutilized, their futures uncertain. They are not unemployed—they are mis-employed, and that may be worse.

If Nigeria continues to celebrate statistical fictions while ignoring structural realities, it will squander its greatest asset: its people. But if it shifts focus from headline unemployment to decent job creation, from subsidy programmes to enabling environments, from symbolic gestures to systemic reform, the demographic dividend remains within reach.

The question is not whether Nigeria can create jobs at scale. It is whether Nigeria’s leaders have the political will to make the hard choices that job creation demands. The clock is ticking. And 4 million young people enter the labour force every year, looking for an answer.