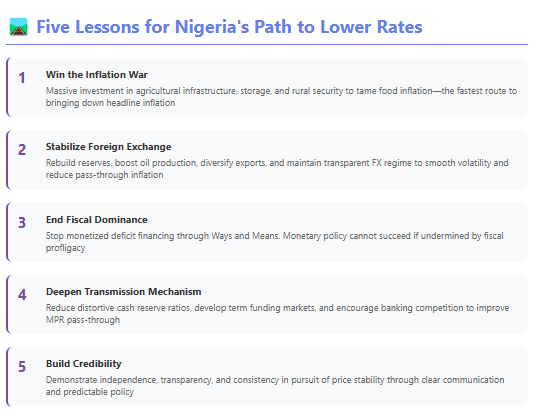

For much of 2024 and into 2025, the global monetary story was one of restrictive policy rates battling stubborn inflation. Yet a small cohort of African economies has maintained benchmark rates well below 5%, offering a striking counterpoint to Nigeria, where the Central Bank held its Monetary Policy Rate at 27.5% through July 2025 before finally cutting to 27% in September—the first reduction since the pandemic.

Understanding why these outliers can afford cheap money matters profoundly. Lower policy rates reduce financing costs for businesses, stimulate household consumption, and—when managed prudently—support steadier, more inclusive growth. More importantly, they reveal what Nigeria would need to fundamentally change to bring borrowing costs down sustainably.

The low-rate league: A diverse group united by stability

As of late 2025, a distinct group of African economies stands out for maintaining exceptionally low central bank policy rates, defying the tightening trend that has characterised much of the continent. Morocco leads with a benchmark rate of 2.25 per cent set by Bank Al-Maghrib, while Algeria follows closely at 2.75 per cent.

Botswana, one of Africa’s most fiscally disciplined nations, operates with a rate of 1.9 per cent. Within the regional blocs, the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), comprising countries such as Cameroon, Chad, and Gabon, holds its common rate at 4.5 per cent through the Bank of Central African States (BEAC). The West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), which includes Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, and Benin, maintains a rate of 3.25 per cent under the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO).

Meanwhile, Mauritius, a small island economy with a robust financial system, keeps its policy rate at around 4.5 per cent under the Bank of Mauritius. Despite their differences in geography, economic structure, and size, these nations share a unifying trait: stability. Some are small, service-oriented island economies; others are resource-rich exporters with significant foreign-exchange reserves; and a few belong to monetary unions anchored by a fixed peg to the euro. Yet, what binds them together is a consistent commitment to macroeconomic discipline, credible institutions, and prudent fiscal management—all of which have allowed them to keep inflation contained and interest rates low without jeopardising financial stability.

The foundations of low rates

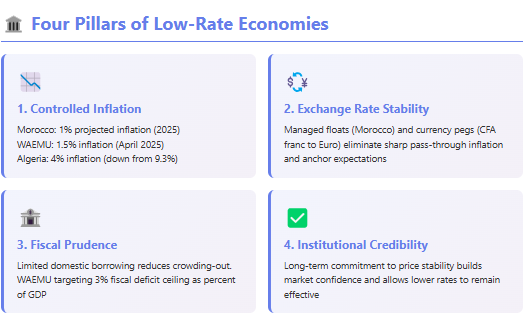

1. Controlled and credible inflation

Morocco’s central bank held its rate at 2.25% in 2025, citing subdued inflation projected at just 1% for the year. Algeria’s inflation cooled to 4% in 2024 from 9.3% the year prior, allowing the Bank of Algeria to lower rates to 2.75%. The WAEMU region saw inflation fall to 1.5% by April 2025, well within the BCEAO’s 1–3% target range, enabling a rate cut to 3.25% in June.

Low and stable inflation is the bedrock. When price pressures are contained, central banks gain the room to set real interest rates low without stoking demand-side inflation or triggering capital flight. In contrast, Nigeria’s inflation—though moderating to around 18.02% (Reuters) after rebasing—remains far too elevated for meaningful rate cuts.

2. Exchange rate stability and external buffers

Morocco operates a managed float, with the dirham pegged to a basket weighted toward the euro and US dollar. This framework, backed by adequate foreign reserves, eliminates the sharp pass-through inflation that plagues countries with volatile, market-determined exchange rates. WAEMU and CEMAC members benefit from their CFA franc pegs to the euro, which anchor inflation expectations and import price stability. Botswana, despite its low rate, maintains foreign reserves sufficient to cover several months of imports, providing confidence that the pula will remain stable. Nigeria’s naira, by contrast, has experienced repeated volatility, forcing the CBN to keep rates high to attract portfolio inflows and defend the currency.

3. Prudent fiscal policy and limited crowding-out

Where governments avoid large, domestically financed deficits, the pressure on domestic interest rates is reduced. Morocco’s fiscal discipline and relatively low debt burden mean its central bank does not compete with reckless government borrowing. WAEMU’s proposed reintroduction of a 3% fiscal deficit ceiling (as percent of GDP) signals renewed commitment to fiscal sustainability.

Nigeria’s persistent fiscal dominance—massive deficits historically financed through Ways and Means advances from the CBN—has crowded out the private sector and forced the central bank to keep rates punitive to mop up excess liquidity and control inflation.

4. Institutional credibility and transmission mechanisms

The central banks of Morocco, Botswana, and the regional blocs have established long-term credible commitments to price stability. Their inflation-targeting or nominal anchor frameworks work because markets believe them. When credibility is high, lower policy rates can still keep inflation expectations anchored. Nigeria’s monetary policy transmission mechanism remains weak. High cash reserve requirements, wide banking spreads, and the legacy of unconventional interventions have blunted the pass-through from the MPR to actual lending rates. Even when the CBN cuts rates, businesses and households may not feel meaningful relief.

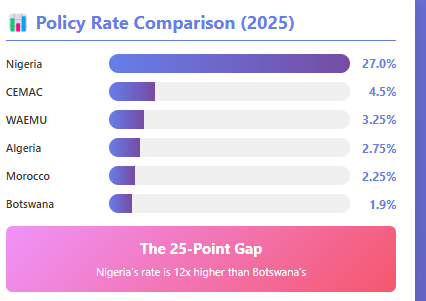

The dividend of cheap money

The benefits to low-rate economies are tangible. In Morocco, affordable credit fuels investment in manufacturing, tourism, and infrastructure. Small and medium enterprises can expand without crippling debt service costs.

The WAEMU’s rate cut to 3.25% is designed to stimulate growth projected at 6.4% in 2025. Mauritius attracts diversified foreign direct investment, in part because predictable, low financing costs make long-term projects viable.

Lower rates also ease the government’s debt service burden, freeing up fiscal space for education, health, and infrastructure—creating a virtuous cycle of stability, investment, and growth.

Lessons for Nigeria: The long road to credibility

For Nigeria, the gap between 27% and Morocco’s 2.25% is not merely numeric—it is a measure of the chasm in our macroeconomic fundamentals. The path to materially lower borrowing costs requires Nigeria to undertake deep, structural reforms:

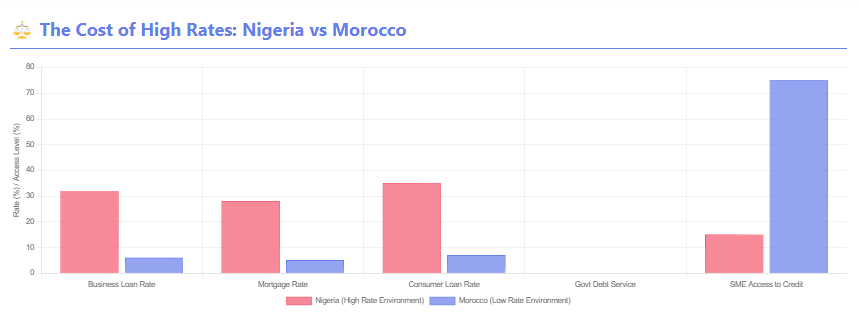

1. Win the inflation war decisively: Nigeria’s most impactful move would be to address food inflation at its root—through massive investment in agricultural infrastructure, storage, rural security, and climate-resilient crops. Taming food prices is the fastest route to bringing down headline inflation.

2. Stabilize the foreign exchange market: The CBN must rebuild reserves to a level that inspires confidence and smooths volatility. This means boosting oil production, diversifying export earnings, and maintaining a credible, transparent FX regime. A stable naira is non-negotiable for lowering inflation and, ultimately, interest rates.

3. End fiscal dominance: The government must commit credibly to ending monetized deficit financing. The National Assembly’s securitization of past Ways and Means debt was a positive step, but only the beginning. Monetary policy cannot succeed if constantly undermined by fiscal profligacy.

4. Deepen the transmission mechanism: Reducing distortive instruments like excessively high, non-remunerated cash reserve ratios, developing term funding markets, and encouraging competition in banking will help the MPR feed through to credit markets at lower cost.

5. Build credibility through consistency: The CBN must continue to demonstrate independence, transparency, and consistency in pursuit of price stability. Clear communication, predictable policy, and a strong institutional track record will lower inflation expectations—making each percentage point of rate cuts more effective.

A final word

Low policy rates are not a policy lever to be pulled arbitrarily—they are the reward for achieving fundamental macroeconomic stability. Morocco, Mauritius, Botswana, and the CFA franc zones show that cheap money is possible on this continent.

But it rests on credibility, not convenience. For Nigerian businesses struggling to borrow, and for citizens yearning for affordable mortgages and consumer credit, the message is clear: we must commit to the long, hard road of fiscal discipline, exchange rate stability, and inflation control. The prize—a thriving, diversified, and inclusive economy powered by affordable capital—is well worth the effort.