The 66th Annual Conference of the Nigerian Economic Society, held in Abuja from September 8-11, 2025, delivered a comprehensive diagnosis of Africa’s development challenges while outlining a pragmatic blueprint for continental transformation. With 249 research papers and contributions from distinguished policymakers, including Vice President Kashim Shettima and WTO Director-General Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the conference theme “Rethinking Africa’s Development: Pathways to Economic Transformation and Social Inclusion” produced critical insights that challenge conventional development wisdom.

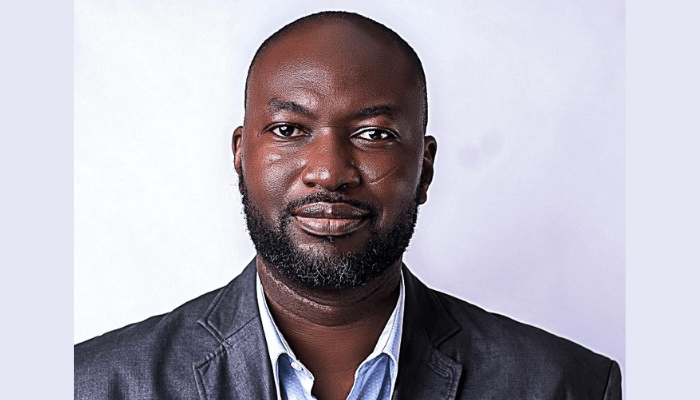

The growth paradox: When numbers deceive

Africa’s macroeconomic statistics mask a troubling reality. Nigeria’s 2.5 percent GDP growth in Q2 2025 coexists with declining real incomes and 40 percent of citizens below the poverty line. This pattern repeats across the continent, where average GDP growth conceals profound inequality and exclusion. The structural problem lies in growth concentration within low-linkage sectors that generate minimal employment. Nigeria’s economy remains heavily dependent on oil exports and services sectors with limited backward and forward linkages, while manufacturing contributes less than 10 percent of GDP. This has left 93 percent of Nigerian employment in the informal sector, offering little productivity, taxation, or worker protection. Infrastructure gaps, particularly in electricity and transport, cripple productivity across the continent. Export baskets remain dominated by raw commodities, while real GDP consistently trails potential output. Even where macro reforms are introduced—such as fuel subsidy removals or foreign exchange unification—they often lack social cushioning and coherence.

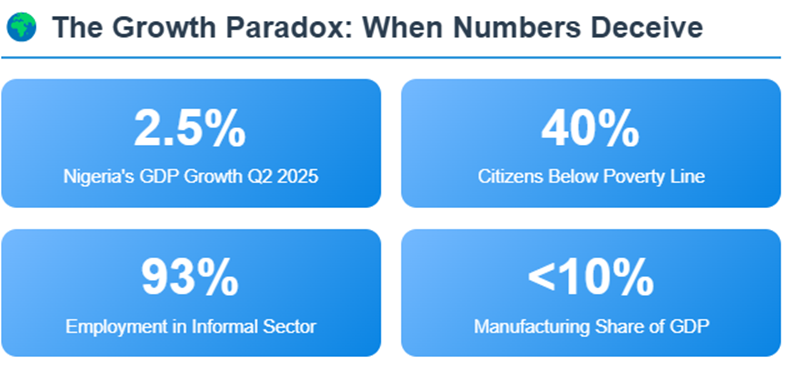

Redefining the debt crisis: Quality over quantity

Conference participants challenged conventional wisdom about Africa’s debt burden, presenting evidence that the continent is actually “under-borrowing” relative to other regions when adjusted for population, GDP, and development needs. The real crisis is not debt volume but debt efficiency and utilisation. Much of Africa’s recent debt has funded recurrent expenditure or poorly executed capital projects, with corruption and procurement inefficiencies eroding economic returns. This efficiency gap explains why African countries simultaneously experience debt stress while remaining unable to finance critical infrastructure and social programmes. Nigeria exemplifies this paradox. Despite revenue increases reaching ₦6.9 trillion, widespread poverty persists because debt structures prioritise servicing over productive investments. The debt landscape has shifted dramatically, with China, India, and other emerging economies replacing traditional Paris Club creditors, while domestic debt now outweighs foreign debt in many African countries. The solution is not debt avoidance but securing efficient, productive, and transparent debt anchored in high-return investments in infrastructure, energy, education, and climate resilience. This requires extensive economic diversification first—productivity growth must lead to income growth, creating broader tax bases.

The data deficit: Planning in the dark

A critical conference finding was the crippling absence of reliable data across Africa. As Dr Okonjo-Iweala emphasised, “Without quality data, policy cannot succeed.” This constitutes more than a technical challenge—it represents a fundamental barrier to effective governance and development. Across the continent, household surveys are infrequent or incomplete, labour statistics are outdated, and national budgets remain opaque. Poor data infrastructure creates multiple development handicaps: governments cannot effectively target interventions, private investors struggle with decision-making, and international partners impose one-size-fits-all solutions. Nigeria’s frequent GDP rebasing exercises reveal significant previously uncounted economic activity, suggesting systematic underestimation of performance. Similarly, poverty measurements vary dramatically depending on methodology, complicating targeted intervention strategies. The conference demanded a data revolution: investments in statistical agencies and digital platforms, standardised open-source databases across ministries, and integration of satellite, fintech, and mobile data for real-time insights.

“Development policies have been insufficiently sensitive to differential impacts on men and women, not only perpetuating inequality but also wasting human capital that could drive development.”

The governance-implementation Gap

Perhaps the most striking observation was the abundance of well-intentioned policies contrasted with weak governance structures that undermine implementation. Nigeria has produced numerous development frameworks over the decades yet continues struggling with basic service delivery and economic transformation. This governance-policy disconnect manifests in political cycles disrupting long-term plans, with new administrations abandoning predecessors’ initiatives regardless of merit. Institutional capacity remains inadequate for complex policy implementation, particularly at subnational levels where development challenges are experienced directly. Vice President Shettima’s acknowledgement that current economic reforms have imposed costs while promising future benefits reflects this implementation challenge. The emphasis on placing economists in key positions represents recognition that technical expertise must complement political will.

Read also: African private sector leaders launch coalitions to tackle learning crisis

Social inclusion: Beyond development rhetoric

Despite decades of programmes and budget allocations, Africa remains among the world’s most unequal and socially excluded regions. Conference participants highlighted persistent challenges: rising income inequality despite economic growth, gender gaps in accessing finance, land, education, and employment, limited financial inclusion, especially in rural areas, and inadequate access to affordable healthcare, housing, and insurance. Nigeria’s rural-urban poverty gap illustrates this dramatically—rural areas experience 75.5 percent poverty rates compared to 41.3 percent in urban areas. Development strategies have favoured urban centres while marginalising rural populations despite their demographic significance. Gender dimensions received particular attention. Development policies have been insufficiently sensitive to differential impacts on men and women, not only perpetuating inequality but also wasting human capital that could drive development. The slow transformation rate is partly traced to “gender insensitivity in development policy initiatives”.

The security-informality twin trap

Economic policy cannot ignore physical realities. Across Nigeria and much of the continent, insecurity has become both an economic and existential threat. Farmers flee fields due to banditry and insurgency, logistics costs soar as roads become dangerous, and investor confidence evaporates. Meanwhile, informal sector dominance—93 percent of Nigerian employment—offers little productivity, taxation, or protection. These twin traps reinforce each other, locking millions into survivalist activities while weakening state capacity to deliver services.

Regional integration: The unfulfilled promise

The African Continental Free Trade Area represents the continent’s most ambitious integration initiative, yet intra-African trade volumes remain disappointingly low. Contributing factors include inadequate transport infrastructure, complex border procedures, currency convertibility challenges, and insufficient information sharing about market opportunities. Nigeria’s relationship with neighbours illustrates these challenges. Despite sharing borders and cultural ties, Nigerian businesses often find trading with Europe or Asia easier than with regional partners. This pattern limits Africa’s ability to leverage collective economic weight in global markets.

Economic reforms: The discipline imperative

Current Nigerian reforms—subsidy removal, exchange rate liberalisation, and tax system overhaul—generated significant discussion. While acknowledging short-term adjustment costs, participants emphasised that reform success depends critically on implementation discipline and consistent political support. Bismarck Rewane’s keynote highlighted lessons from the Asian Tigers, whose successful transformation required sustained commitment despite initial hardships. The challenge lies in maintaining reform momentum while managing social and political pressures that often derail programmes. The conference emphasised “people-oriented” reforms that consider social impacts while pursuing economic efficiency, requiring robust social protection systems to cushion vulnerable populations during transitions.

Transition states: No country left behind

Conference participants warned that Africa cannot develop while parts disintegrate. Fragile states—plagued by conflict, displacement, and weak institutions—drag down regional stability and economic progress. These states grapple with insecurity, governance issues, low growth, infrastructure deficits, climate change, and poverty-induced displacement. Their lack of capacity for driving economic development poses serious hindrances to Africa’s transformation agenda.

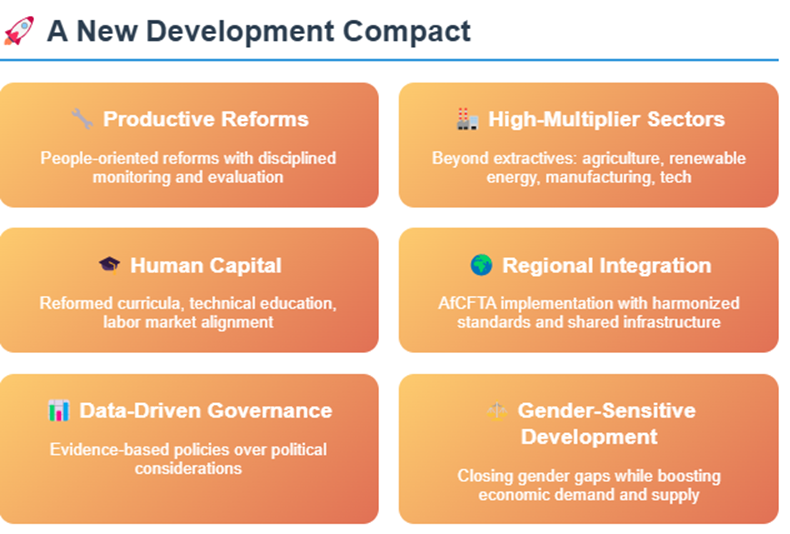

A new development compact

The conference outlined a comprehensive framework for transformation that emphasises the critical importance of productive, people-oriented reforms. These current reforms must include disciplined monitoring, evaluation, and necessary adjustments while remaining people-oriented throughout their implementation to ensure sustainable progress. Central to this framework is strategic investment in high-multiplier sectors that move beyond traditional extractive industries toward more diversified economic activities. This includes prioritising agricultural mechanisation to boost food security and rural productivity, developing renewable energy infrastructure to power sustainable growth, fostering light manufacturing to create employment opportunities, and expanding technology services to position countries competitively in the digital economy.

The compact recognises human capital as a core strategic asset, emphasising education and skills development through comprehensive reforms. This involves implementing reformed curricula that align with modern economic needs, scaling technical education programmes to meet industry demands, and establishing training systems that are directly linked to labour market requirements to ensure graduates can contribute meaningfully to economic development. Regional integration emerges as another cornerstone through the intentional implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). This requires harmonising standards across member states, developing shared infrastructure that facilitates trade and movement, and systematically removing trade barriers that have historically fragmented African markets and limited economic potential.

Read also: North Africa dominates, as Africa’s gold reserves hit $91.7 billion

The framework also emphasises the necessity of data-driven governance, advocating for policies that are grounded in empirical evidence rather than political considerations. Quality data collection and analysis are positioned as essential tools for improving policy success rates and ensuring that development interventions achieve their intended outcomes. Finally, the compact calls for gender-sensitive development approaches that are specifically designed to close persistent gender gaps. These policies should simultaneously boost economic demand and supply by enhancing household incomes, recognising that women’s economic empowerment creates multiplier effects that benefit entire communities and national economies.

The path forward

The NES 2025 conference provided clarity rather than platitudes: Africa’s development challenge concerns not resources but how they are governed, distributed, and invested. It called for discipline in reforms, inclusion in planning, accountability in spending, productivity in debt, trust in taxation, and realism in policymaking. The conference demonstrated that Africa possesses both intellectual capacity and policy frameworks for accelerated development. The continent’s challenges are significant but not insurmountable given appropriate strategies and sustained implementation commitment. Success requires homegrown solutions that leverage local knowledge while engaging constructively with global trends. Africa stands at a critical juncture where demographic dividends, natural resource endowments, and growing global recognition create unprecedented transformation opportunities.

Conclusion: From potential to performance

The time for transformation is now. Africa must move from plans to performance, from pronouncements to outcomes, and from potential to delivery. This rethinking will be difficult but essential, because development delayed is not just development denied—it is destiny deferred. Whether opportunities translate into tangible outcomes depends on policy choice quality and implementation capacity demonstrated by African leaders. The path demands both ambition and realism—ambition to pursue transformative change while maintaining realistic expectations about implementation timelines and political constraints. Most importantly, sustainable development is ultimately about improving citizens’ lived experiences, not just achieving macroeconomic targets. The blueprint from Abuja is clear. The question remaining is whether Africa’s leaders possess the focus and fortitude to build upon it, choosing disciplined, inclusive policies over continued celebration of statistics while poverty deepens.

Dr. Oluyemi Adeosun, Chief Economist, BusinessDay Media