Despite inflation averaging 23.5 percent in 2025, NBS data reveals that prices of more than 72 percent of essential commodities are still on the rise month-on-month.

Since the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) rebased Nigeria’s inflation figure, also known as the Consumer Price Index (CPI), in January 2025, headline inflation has been on a consistent decline, falling from 24.5 per cent to 22.22 per cent by June. The only deviation from this downward trend occurred in March, when inflation briefly surged to 24.23 percent.

Yet, despite these seemingly positive numbers, Nigerians continue to question why the realities on the ground remain unchanged, or, at best, marginally improved. If inflation is falling, why does life still feel just as expensive?

At the heart of the issue lies food inflation. The food inflation index rose from 110.3 in January to 123.4 in June, an 11.86 percent increase in just six months. In other words, while headline inflation appears to be softening, the prices of essential food items are rising at a steady pace. In January, food prices had only increased by 10.3 percent compared to the 2024 base year. By June, they had surged by 23.4 percent, more than doubling in relative terms, yet the headline inflation figure was declining.

Agricultural inflation tells a similar story. The farm produce index rose sharply from 110.5 in January to 142.5 in May, a staggering 28.95 percent rise, before easing to 123.6 in June. This suggests that domestically produced food, often seen as a hedge against import-driven inflation, is also becoming increasingly unaffordable. The road to food self-sufficiency, it appears, is longer than we think.

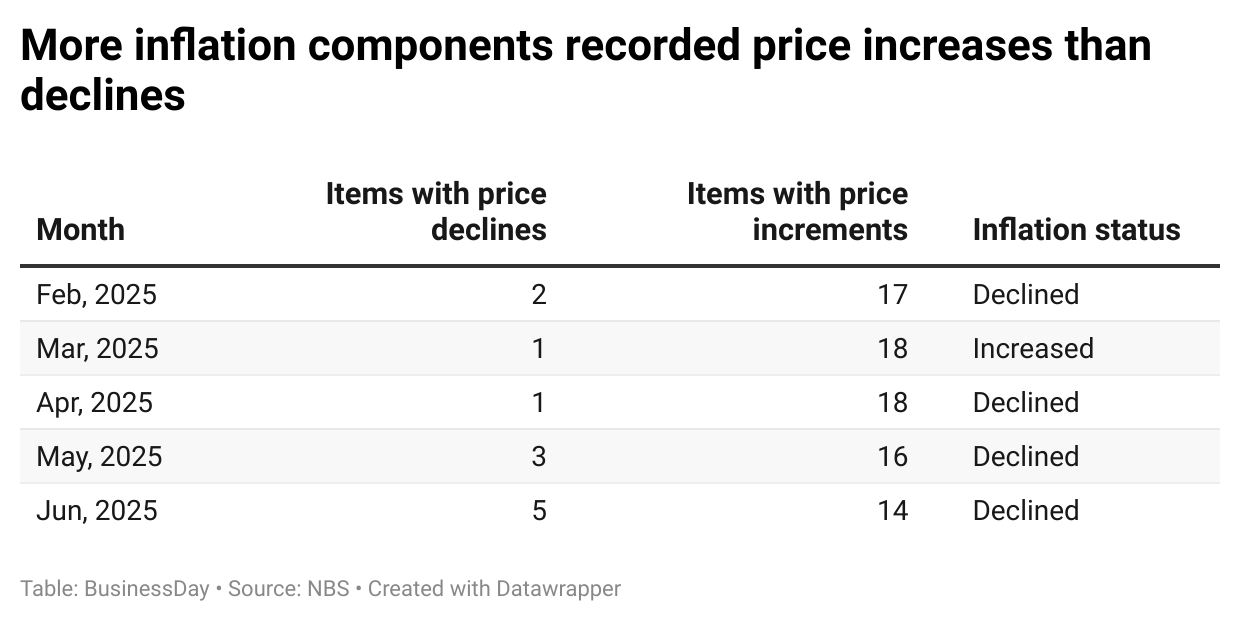

Among the 19 components of the inflation basket published by the NBS, only five items recorded a decline in their indices month-on-month from May to June 2025. These were: imported food, farm produce, energy, goods, and education services. Every other component recorded increases.

A deeper dive from February to May tells a similar story. In February, only Energy, Clothing and Footwear saw declines. In March, it was only Restaurants and Accommodation Services. In April, just Food & Non-Alcoholic Beverages declined. And in May, there were only three declining components.

But here’s the thing, the average Nigerian makes financial decisions based on daily or monthly changes, what they spent this month compared to the last. Yet what appears as headline inflation is simply the official method employed by the NBS, which largely focuses on year-on-year comparisons, such as comparing May 2025 to May 2024.

Despite a drop in average inflation to 23.5 percent, NBS data reveals that prices of more than 72 percent of essential commodities are still on the rise

This disconnect creates a troubling perception gap. It can suggest that Nigerians are experiencing “relief” on paper, while in reality, their household budgets and market visits tell a very different story.

Inflation numbers that raise more questions than they answer

One particularly troubling moment came with May’s inflation data. The NBS reported that headline inflation increased by only 1.53 percent month-on-month. Yet a close analysis of the underlying data revealed that nearly all major categories had increased, except for energy and transport, which together represent a modest 17.08 percent of the CPI basket.

This contradiction was sharply criticised by Adedayo Bakare, an economist, who wrote in his Substack essay, On Inflation Numbers That Make No Sense: “If almost everything in the basket is rising in price, how then does the overall inflation barely move? Either the weighting is flawed, or the calculation is masking what consumers are truly facing.”

Further confusion was stirred by the NBS’s own language in the May inflation report. It stated: “On a month-on-month basis, the Food inflation rate in May 2025 was 2.19 percent, up by 0.12 percent compared to April 2025 (2.06%). The increase can be attributed to the rate of decrease in the average prices of Yam, Avenger (Ogbono/Apon), Cassava Tuber, Maize Flour, Fresh Pepper, Sweet Potatoes, etc.”

How does a decrease in food prices lead to an increase in the inflation rate? Was the NBS trying to say that the inflation rate would have been even higher were it not for these price drops? The language was, at best, ambiguous—and at worst, misleading.

Credibility crisis: Local and global concerns

These inconsistencies haven’t escaped the attention of financial experts. Abdulrauf Bello, a finance analyst, expressed open scepticism about the data’s reliability. In a widely shared commentary, he noted that “World Bank: the NBS inflation data computation seems flawed. We don’t understand it. IMF: the NBS inflation data is inconsistent. And we somehow want foreign investments when we cannot even get it right with simple inflation data. Anyway, I stopped checking it in December last year.”

Bello’s remarks are symbolic of a larger crisis of credibility. How can effective policymaking or investor confidence be built on flawed, unclear, or contradictory data?

Even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has weighed in. In its 2025 Article IV consultation report on Nigeria released on the 2nd July 2025, the IMF flagged the quality and timeliness of inflation data as a key concern: “Data shortcomings are somewhat hampering surveillance… Complete publication of the rebased CPI data has been delayed, and setting December as the index reference period rather than following the common approach of using an annual index reference period inhibits the assessment of the inflation level and trend.”

Put simply, the IMF is arguing that the current method used by the NBS, particularly after rebasing the CPI, makes it difficult to track inflation trends over time. By anchoring everything to December rather than adopting a standard annual reference, month-on-month comparisons become less meaningful and harder to align with global norms.

Paper gains, real pain

Taken together, these concerns from economists, institutions, and consumers suggest a growing disconnection between official inflation statistics and the economic realities Nigerians are grappling with. While the headline figures may suggest a softening of inflation, the prices of essentials, particularly food, tell a very different story, and it is evident in the inflation food basket data as computed by NBS.

And when inconsistencies, opaque methodologies, and vague statements dominate national data, public trust begins to erode. For citizens trying to make sense of rising food prices amid reports of falling inflation, the numbers don’t just seem confusing; they feel irrelevant.