In a country once defined by oil, NigeriaтАЩs economy is undergoing a quiet transformation. The real engine of growth is no longer found in pipelines or refinery gates, but in fields, markets and smartphones.

A recent change in how the economy is measured has brought this shift into sharp focus. Known as GDP rebasing, the exercise updates the way the country calculates its economic output, using fresher data to reflect how Nigerians actually earn and spend. And the results tell a different story.

The long-held image of an oil-fueled, industry-led economy is fading. Agriculture and services have grown in prominence, while industry especially manufacturing, has shrunk.

The new breakdown

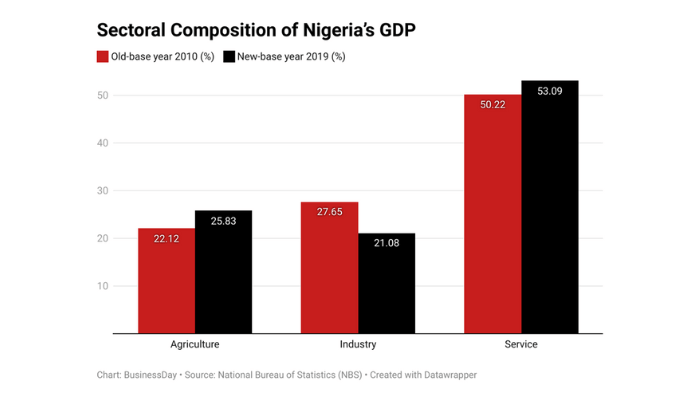

Based on the old calculation method using 2010 prices, NigeriaтАЩs 2019 economy was estimated to comprise 22.1 percent agriculture, 27.7 percent industry, and 50.2 percent services. The revised data tells a different story: agriculture now accounts for 25.8 percent, industry has dropped to 21.1 percent, and services have grown to 53.1 percent.

The numbers may seem technical, but the implications are deeply personal. AgricultureтАЩs rise reflects what rural households already experience: Farming is central to survival, not a last resort.

Read also:┬аNigeriaтАЩs GDP grew by 3.13% in Q1 2025 after rebasing

Economy gaps

Still, not everyone is convinced this reflects real progress. тАЬIn my opinion, while the rebasing is timely, productivity has not increased in the real sense. We are still operating below potential,тАЭ said Abdulbasit Shuaib, an economist who works for a multinational company.

His concern is echoed in parts of the country where daily realities still donтАЩt match the story that rebased data suggest.

The sharp drop in industry signals the deepening struggles of factories facing power cuts, high input costs and unclear regulation. Services, meanwhile, remains the real growth story, from logistics and mobile banking to barbershops and social media marketing.

WhatтАЩs changing on the ground?

For the average Nigerian, this shift means the economy is finally catching up with lived experience. Most people donтАЩt work in oil rigs or factories. They sell, deliver, sew, code, plant or drive. These activities once sidelined in policy conversations are now the countryтАЩs economic core.

The rebasing makes one thing clear: NigeriaтАЩs economy is not just about exports or revenue from crude oil. ItтАЩs about people making things work in a difficult environment often informally, often without support.

This should shape how governments plan, analysts say. Investing in rural roads, irrigation, mobile connectivity, and urban transport would go further than another tax break for oil multinationals. If agriculture and services are where people find work and income, then thatтАЩs where support should go.

Pain in the factory belt

IndustryтАЩs decline is more than just a statistical dip. ItтАЩs a sign that local manufacturing once seen as the great hope of economic diversification is in distress. Many firms are scaling back or shutting down due to unreliable electricity, multiple taxes, expensive imports and crumbling infrastructure.

The Manufacturers Association of Nigeria (MAN) said that 767 manufacturers shut down operations while 335 became distressed in 2023.

This is a concern to analysts as industrial jobs tend to be more stable, formal and export-oriented. Manufacturing also supports wider value chains from suppliers to transporters. Letting it wither could mean giving up on balanced growth and long-term competitiveness, they say.

Reversing this trend will take more than rhetoric. It will require coordinated reform: stable power, affordable finance, targeted support for local inputs, and a tax system that doesnтАЩt punish productivity, experts further say.

Read also:┬аNigeria remains fourth largest economy in Africa despite rebasing

The rise of services sector

Services now drive more than half of the economy. Some of this is in banking, telecoms and finance. But a lot of it is informal: ride-hailing, online retail, cleaning services, logistics.

This growth is not without risk. Informal jobs often lack protection, benefits or consistent pay. But they also show innovation and resilience. With limited resources, Nigerians are building solutions and serving growing demand.

тАЬTo make this sustainable, the government must catch up. It needs to expand digital access, offer vocational training, improve broadband coverage and enact laws to protect both businesses and consumers,тАЭ an economist said.

Not just accounting exercise

GDP rebasing is not just about new numbers. It is a mirror. And what it shows is that NigeriaтАЩs economy is changing quietly, rapidly and from the bottom up.

While it gives investors and policymakers a clearer picture of where growth is happening, it doesnтАЩt solve deeper economic challenges.

тАЬRebasing is good because it shows where the economy is performing and where investors can direct their funds,тАЭ said Marcel Okeke, former chief economist at Zenith Bank. тАЬBut for real impact, issues like inflation, insecurity and poor infrastructure must also be tackled. Those are the factors that truly drive economic confidence.тАЭ

Yet some analysts caution that these changes, though useful on paper, may obscure deeper weaknesses. тАЬThis economy is far below its potential as the data suggest. $250 billion is quite abysmal. In naira terms, there is growth. You see, with the exchange rate thing, comparative analysis on a global scale will continue to put us at the end of the table,тАЭ said Oluwatobi Abisoye, a financial and corporate report analyst.

Oil still matters. But it no longer defines the economy or the future. NigeriaтАЩs real strength now lies in its farmers, tech entrepreneurs, traders, and workers. Recognising and investing in this reality may be the difference between fragile recovery and lasting growth.

тАЬTo move forward, Nigeria must stop chasing legacy sectors and start backing the real economy: its people, their ideas, and the sectors where their labour actually lies,тАЭ a policy analyst noted.