Across Africa, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer defined by massive data centres, billion-dollar compute budgets or cutting-edge laboratories.

Instead, a quieter but more transformative shift is underway: the rise of “Small AI”, lightweight, mobile-friendly and context-specific tools that are allowing African countries to leapfrog traditional barriers and reshape how technology is adopted on the continent.

From Kenya’s grassroots use of generative AI on smartphones to Nigeria’s mobile-driven fintech bots and South Africa’s sector-focused enterprise deployments, African nations are rewriting the global AI playbook in ways that prioritise access, affordability and real-world impact.

South Africa remains the continent’s most advanced AI market, benefiting from strong infrastructure, mature regulation and deep private-sector investment. With internet penetration nearing 75 percent and local cloud infrastructure from global providers, the country has embedded AI across healthcare, agriculture, finance and public safety. AI-powered medical imaging, predictive credit scoring and drone-based crop monitoring are no longer pilot projects but operational tools. Yet even in South Africa, growth is increasingly driven by modular and scalable AI systems that can operate efficiently without extreme computing power.

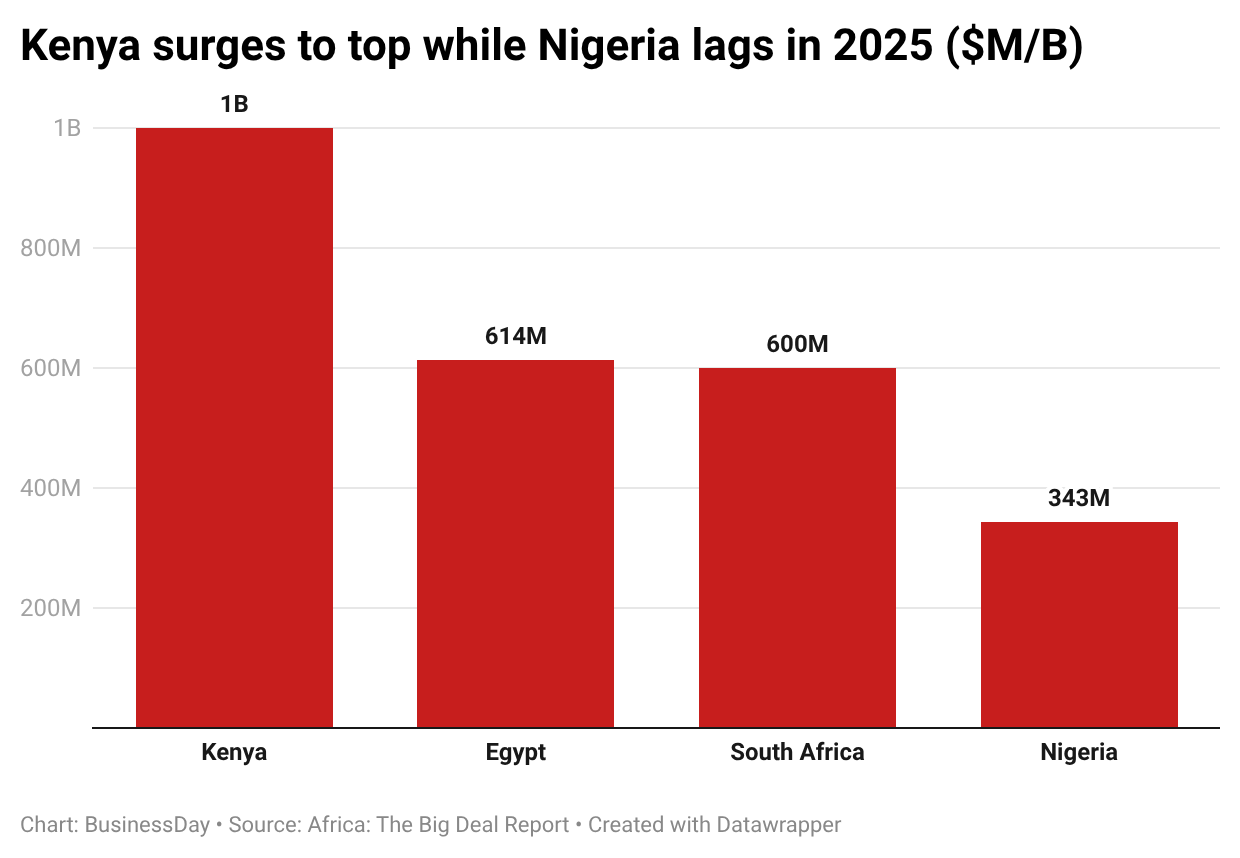

Kenya offers perhaps the clearest example of how “Small AI” is changing adoption dynamics. By mid-2025, more than 42 percent of Kenyan internet users aged 16 and above were using ChatGPT, the highest rate in Africa. This surge has not been led by big corporations, but by students, informal workers, teachers and small businesses integrating AI into daily tasks through smartphones. In classrooms, generative AI supports personalised learning; in healthcare, chatbots assist maternal care; and in agriculture, mobile-based AI tools help farmers make planting and pricing decisions. Kenya’s experience mirrors its earlier mobile money revolution, showing how bottom-up adoption can scale rapidly when technology fits local realities.

Read also: Africa’s next unicorns: 18 Startups in hunt for $1bn valuations or IPOs in 2026

Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, is following a similar mobile-first path, even as it confronts deeper structural challenges. By mid-2025, about 9.3 percent of Nigeria’s working-age population had adopted AI tools, with growth driven largely by open-source platforms and “Small AI” applications that bypass costly subscriptions and heavy computing requirements. Over 120 AI-focused startups are now active in the country, applying AI to banking, telecommunications, agriculture and healthcare.

In financial services, Nigerian banks and fintech firms are deploying AI for fraud detection, credit assessment and document verification, while telecom operators have rolled out generative AI chatbots to improve customer support and service activation. Agriculture and health startups are using AI to improve diagnostics and crop forecasts, demonstrating how narrowly focused tools can deliver outsized impact in resource-constrained settings.

Crucially, Nigeria is also moving to pair innovation with regulation. The government is set to approve a comprehensive legislative framework to govern artificial intelligence through the proposed National Digital Economy and E-Governance Bill. The bill would grant the National Information Technology Development Agency (NITDA) formal authority over algorithms, data governance and digital platforms, closing long-standing regulatory gaps left by the draft national AI strategy released in 2024.

If passed, the legislation will introduce a structured, risk-based approach to AI oversight, with heightened scrutiny for systems used in public administration, finance, automated decision-making and surveillance. Developers would be required to register or obtain licences before deploying AI systems, while high-risk applications would face mandatory annual audits. Regulators would also gain enforcement powers, including fines of up to N10 million or up to 2 percent of an AI provider’s annual gross revenue, as well as the ability to restrict or block harmful systems.

At the same time, the bill aims to avoid stifling innovation. Provisions are designed to support startups and early-stage companies by creating a controlled environment that encourages experimentation while managing risks.

“Regulation is not just about giving commands. It is about influencing market, economic, and societal behavior so people can build AI for good,” said Kashifu Abdullahi, director general of NITDA.

Lawmakers are expected to approve the bill by March 2026, a move that could make Nigeria one of the first African countries with enforceable AI legislation and set a precedent for the continent.

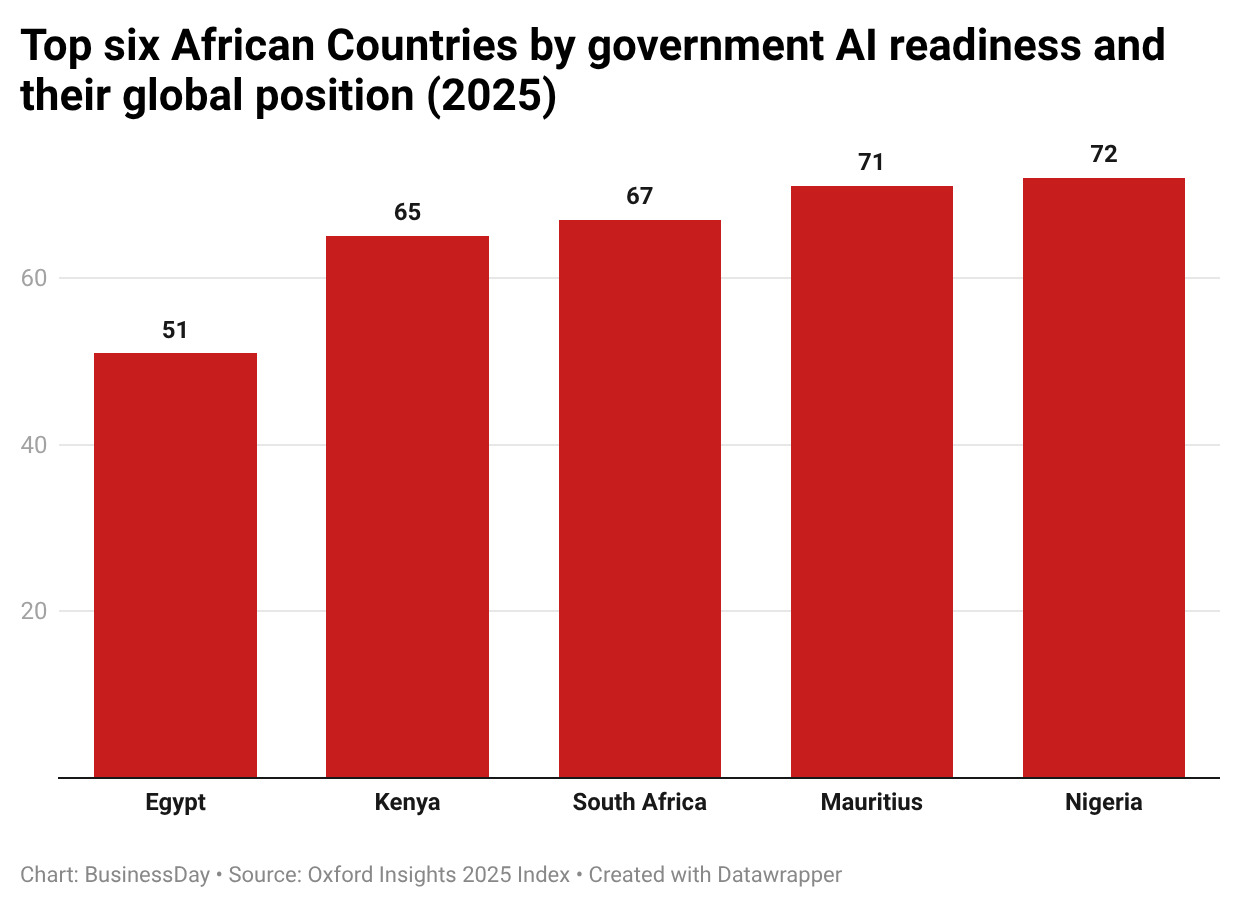

Elsewhere, Morocco and Egypt are advancing enterprise-led AI models, focusing on banking, telecommunications and retail, while Rwanda is positioning itself as a governance and policy leader despite relatively low adoption rates. Rwanda’s National AI Policy, Responsible AI Office and cloud-first strategy reflect an ambition to become “Africa’s AI Lab,” emphasising ethics, skills and targeted sectoral use rather than mass deployment.

Across the continent, common challenges persist: limited access to computing power, uneven connectivity, language and data gaps, and low venture capital inflows.

Yet these constraints are precisely what have made “Small AI” so powerful in Africa. Lightweight, mobile-friendly tools are enabling countries to sidestep infrastructure deficits and tailor AI to local needs.

By 2030, AI could contribute up to $2.9 trillion to Africa’s economy. But the continent’s most important contribution may be strategic rather than monetary. By proving that AI does not have to be big, expensive or centralised to be transformative, African countries are showing the world a different path, one where small systems deliver big impact, and innovation grows from the ground up.