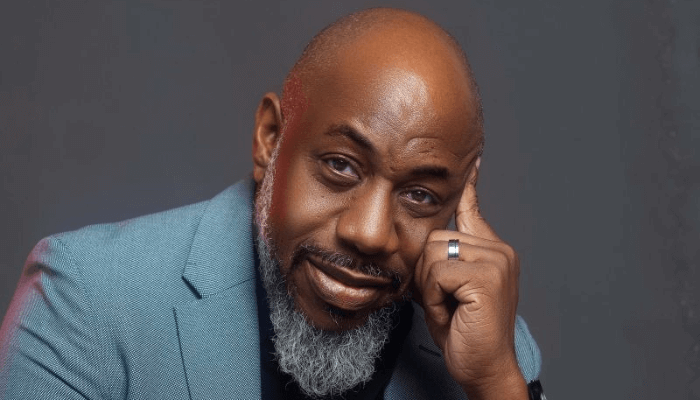

Kofi Abunu is a senior hospitality executive with over three decades of experience driving growth and operational excellence within the Quick Service Restaurant (QSR) industry across Africa and the United Kingdom. He is currently the managing director and chief executive officer of Food Concepts, a leading QSR group focused on delivering affordable, quality meals at scale. It is the group company of Chicken Republic and Pie Xpress. In this interview with Feyishola Jaiyesimi, he discusses how infrastructural gaps limit Nigeria’s agricultural sector and how players in the food business can scale up.

Nigeria loses an average of N3.5 trillion annually to post-harvest. From your experience as CEO of Food Concepts, what is driving this food loss? Is it production, storage, transportation or processing? Or a combination of all four?

From my experience, the challenge is a combination of all four, but the biggest failure is post-harvest handling, especially storage and transportation. Nigeria’s food system is also challenged by fragmented smallholder farming, limited access to affordable finance, unreliable power supply, and policy uncertainty.

Read also:¬†FG targets ‚ā¶1.5trn agricultural financing boost for mechanisation, post-harvest systems

These issues lead to inconsistent supply, higher waste, and elevated costs across the value chain. The solutions lie in farmer aggregation and offtake-led models, improved access to value-chain financing, stronger quality and safety enforcement, investment in reliable and renewable energy for processing, and stable, predictable policies.

With coordinated public and private sector action, especially through structured players like QSRs, these gaps can be turned into opportunities for a more efficient and resilient food system.

The Manufacturers Association of Nigeria says that businesses spent over N1 trillion on alternative power sources in 2024. As someone stirring the affairs of a global food business, how much does inadequate power add to the cost of food production?

Infrastructure deficiencies materially inflate the cost base of food production and the operations of our industry.

In practical terms, unreliable power, weak transport networks, and limited cold-chain infrastructure can push operating costs up by as much as 25-30 percent, with energy and logistics accounting for the largest share.

These inefficiencies show up in higher input losses, slower turnaround times, and increased compliance costs around food safety.

However, the QSR sector has adapted faster than most. By leveraging scale, standardised processes, and technology, operators have been able to manage these pressures while keeping prices accessible for consumers.

The result is a sector that continues to grow, create jobs, and attract investment, even in a challenging infrastructure environment.

Several major food companies invest heavily in power, water, logistics and storage systems. At what point does self-provisioning become unsustainable for the private sector?

Self-provisioning becomes unsustainable when it starts to divert capital, management attention and technical expertise away from a company’s core purpose of serving customers efficiently.

While businesses often invest in their own power, water, logistics or storage systems to manage immediate risks, they come with significant hidden costs.

Beyond installing generators or water plants, companies must contend with ongoing expenses such as sourcing and managing quality diesel, maintaining complex equipment, running water treatment facilities, and ensuring regulatory and environmental compliance.

These costs steadily accumulate into the operating structure of the business and, inevitably, flow through to consumer prices.

The private sector cannot (and should not) be a long-term substitute for public infrastructure. The objective is resilience, not isolation.

Sustainable growth ultimately depends on reliable national systems and strong public-private collaboration, where the government provides enabling infrastructure and businesses can focus on innovation, scale and value creation rather than running utilities on the side.

Read also: Right temperatures to store foods for maximum nutrient retention

How can Nigeria tackle its rising food imports and boost local sourcing?

From a QSR perspective, the key infrastructure is what connects farms to markets.

As I mentioned earlier, priority investments should be in rural roads, cold-chain logistics, and food processing facilities to reduce post-harvest losses and improve consistency.

Nigeria already produces many of the inputs we need; the challenge is moving, storing, and processing them efficiently.

Reliable power and water are still one of the most critical infrastructures to lower costs across the value chain. To boost local sourcing, the government should support structured offtake agreements between QSRs and local producers.

With the right infrastructure, QSRs can scale local sourcing quickly and reduce reliance on imports within a few years.

If Nigeria does not close its food infrastructure gap, particularly around storage, transport and processing, what are the long-term implications for the country?

If Nigeria fails to close its food infrastructure gap, particularly in storage, transport and processing, the long-term consequences will be higher food inflation, persistent post-harvest losses and growing food insecurity.

For the quick-service restaurant sector, weak logistics and cold-chain systems drive up costs, disrupt supply and limit local sourcing at scale.

These infrastructure and logistics challenges also make it more difficult and expensive to open new stores in some regions of the country, slowing expansion and job creation.

Closing these gaps is critical to unlocking Nigeria’s agricultural potential, strengthening food businesses, and ensuring long-term economic stability.

What role should companies like Food Concepts realistically play in fixing these challenges?

Companies like Food Concepts have an important catalytic role to play. We can invest responsibly, build resilient and efficient supply chains, and support local producers by providing scale, standards, and access to markets.

Through innovation and disciplined execution, we can help improve productivity and food availability.

That said, these challenges cannot be solved by the private sector alone. Lasting solutions depend on strong public infrastructure, consistent and enabling policies, and deliberate collaboration between government and business.

When these elements work together, companies like ours can create sustainable impact at scale.

How has Food Concepts structured its operations to scale in an environment where core infrastructure like electricity, transport and storage largely has to be self-provided? Especially in the wake of several exits by top firms.

Operating a QSR business in Nigeria requires resilience by design. At Food Concepts, we structured for scale early by building strong in-house capabilities around power, logistics and cold-chain storage, supported by disciplined process standardisation across our brands.

We invest in central production and distribution hubs to drive efficiency, quality control and cost optimisation, while leveraging technology to improve forecasting, inventory management and speed to market.

Importantly, QSR remains a positive long-term story: demand is driven by Nigeria’s young, urban and increasingly convenience-seeking population.

While some exits reflect firm-specific or short-term pressures, our focus on local sourcing, operational efficiency, and adaptive formats allows us not just to withstand infrastructure gaps but to grow sustainably within them.

How do logistic conditions shape your sourcing, storage and distribution decisions, and what balance have you had to make between efficiency and product quality?

Logistics conditions are central to how we run a QSR business because speed, consistency, and food safety are non-negotiable.

We source 97 percent of our produce locally to reduce lead times, manage costs, and support Nigerian producers, while critical inputs are carefully imported to maintain brand standards.

Read also:¬†We no longer beg food ‚Äď Abia LIFE-ND homestead farmers

Our storage and distribution decisions focus on cold-chain integrity, reliable last-mile delivery, and redundancy to manage infrastructure and traffic challenges.

The balance between efficiency and quality is deliberate: we may incur higher logistics costs to protect freshness, safety, and consistency across our outlets. In QSR, efficiency drives scale, but product quality protects the brand, and quality always takes priority.

Which specific private investments do you think would deliver the biggest reduction in post-harvest loss in Nigeria?

The biggest reductions in post-harvest loss come from investments in cold chain infrastructure, modern storage, and efficient logistics, especially for perishable products.

For a QSR business of our size, strategic partnerships are also critical. Over the last few years, we have strengthened backward integration by working closely with poultry farmers and vegetable growers, providing market certainty and improved handling standards that significantly reduce waste.

Together, these targeted investments create a more efficient and resilient food supply chain in Nigeria.

How can large food companies structure investments directly or through private-public partnerships to extend storage and processing infrastructure beyond their own operations and reduce losses across the wider value chain?

Large food companies can reduce losses across the value chain by investing in shared storage, cold-chain, and processing infrastructure that extends beyond their own operations.

Through public-private partnerships, private sector efficiency can be combined with public scale to deliver sustainable, widely accessible infrastructure.

This model is already being applied in the private sector, where companies with excess cold-room capacity lease space to other food businesses, reducing duplication and the capital required to build standalone facilities.

By expanding shared-use infrastructure, large food companies help stabilise supply, improve quality, and significantly cut post-harvest losses across the ecosystem.