The most expensive mistake in the world is a bridge that leads to nowhere.

Over the last decade, I have sat in boardrooms and government offices across the continent, watching billions of dollars in capital, both private and public, poured into solutions that the market simply didn’t want. I have watched grand agricultural schemes collapse because they were built on rainfall data from the 1970s. I have seen FMCG giants lose millions in inventory because they guessed where the demand was, only to find the middle class they were targeting existed only on a spreadsheet, not on the street.

In my years of building and observing, I have learnt one undeniable truth: economic systems don’t fail due to lack of ambition. They fail because they have lost their connection to reality.

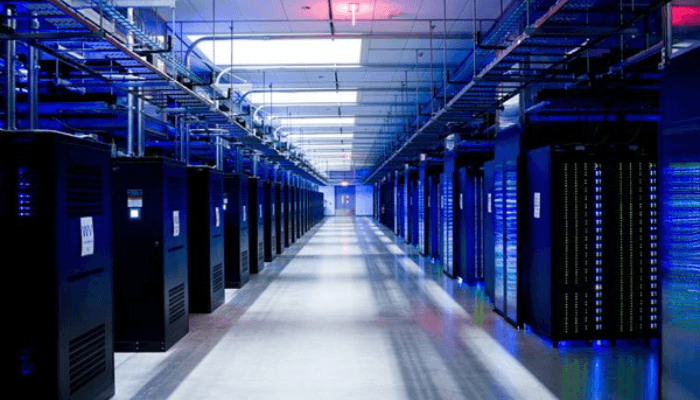

We are obsessed with physical infrastructure: roads, rails, and fibre optics. And in the Global South, we are missing the most critical layer of all: the data infrastructure required to make those physical assets work. We are building skyscrapers on sand, and the sand is shifting.

The Estonia experiment: The power of connective tissue

To understand what we are missing, we have to look 4,500 miles north to Estonia. In the early 90s, Estonia was a post-Soviet state with zero resources. They couldn’t afford to waste a single euro. So, they did something radical: they built the X-Road.

The X-Road wasn’t a giant, scary government database. It was a “data exchange layer”. It allowed different systems – hospitals, banks, schools, and police – to talk to one another securely. It created “interoperability”. Because the data moved freely and securely, the government didn’t have to ask a citizen for the same information twice.

In 1992, Estonia was poorer than much of the modern Global South. Instead of chasing capital for physical monuments, they built a “Digital Republic”. By prioritising data connectivity over prestige projects, they “downloaded” 800 years of productivity and leapfrogged decades of development. Estonia didn’t build data infrastructure because they were rich; they built it to become rich. Today, Estonia is the world’s most digitally advanced society and the number 1 producer of unicorns per capita in Europe.

In the Global South, we are currently building in reverse. Our data is trapped in silos. The Ministry of Health doesn’t know what the Ministry of Transport is doing. The bank doesn’t know what the street vendor is selling. We are operating in a state of “information asymmetry”, where the people making the decisions are the ones furthest away from the outcomes.

The “Reality Gap”

In emerging markets, the informal economy is the economy. But because it is informal, it is invisible. When a street vendor makes a decision, it’s based on ground-truth data. Yet, by the time that signal reaches a policymaker, it has been filtered through layers of consultants and outdated surveys.

This is the reality gap. For a decade, I’ve watched this gap swallow businesses whole, fintechs building apps for people without data and logistics companies buying trucks for roads that vanish in the rainy season. Money is a lubricant, but data is the engine. Without the engine, you’re just pouring oil on the floor.

Interoperability: The Holy Grail

“Interoperability” is more than technical jargon; it is a human rights issue. When systems don’t talk to each other, the poor pay a “knowledge tax”, proving their identity repeatedly to every agency.

To unlock the next billion, we don’t need more shiny apps. We need verified data gathering. We need a system where a signal from a northern village is as credible and pluggable as a report from a Tier-1 bank.

Moving from stealth to scale

The core issue here is the difficulty of developing intelligence in Africa, where data is scarce or distorted. Over the past 18 months, I’ve been working quietly at Melon to build the frameworks we need to actually gather that data ourselves. The focus has been on recruiting and training young agents to act as human sensors, enabling the collection of structured, geotagged, and verifiable data from the real economy in the Global South. That work has evolved into a three-tiered architecture:

Galia, a boots-on-the-ground mobile platform, launches publicly in days and turns ordinary citizens into contributors, allowing millions to report on products and services and reclaim visibility.

Kajari, the eye in the sky, is already being used by market leaders to translate those signals into real-time, high-resolution geospatial insight for both private and public decision-makers.

The Melonverse sits quietly underneath it all, the connective tissue, providing a secure, interoperable space where private signals can meet public needs.

Day zero

The emergence of participatory data tools addresses the historical imbalance in knowledge production about the Global South, where individuals were often viewed merely as subjects of study by external institutions. This new model emphasises the role of citizens not just as data points but as active contributors to collective intelligence. By enabling those within an economy to document their experiences, the information generated becomes more relevant and actionable. This shift is essential for making previously hidden data visible, which is not only a technological advancement but also a critical economic necessity for effective capital, policy, and service functioning.

This is day zero. The highway is open.

Ayokunle Omoniyi is the founder of Melon, a data technology company building interoperable data infrastructure for emerging markets across Africa. With a background in impact measurement, public health, clean energy and geospatial data systems, he has spent over a decade working with governments, investors, and enterprises to close the gap between on-ground realities and decision-making. His work focuses on verified data gathering, data exchange, and turning informal signals into actionable intelligence. He can be reached at ayokunle@melon.ng.