…From allegations of Christian genocide to airstrikes and a billion-naira lobby

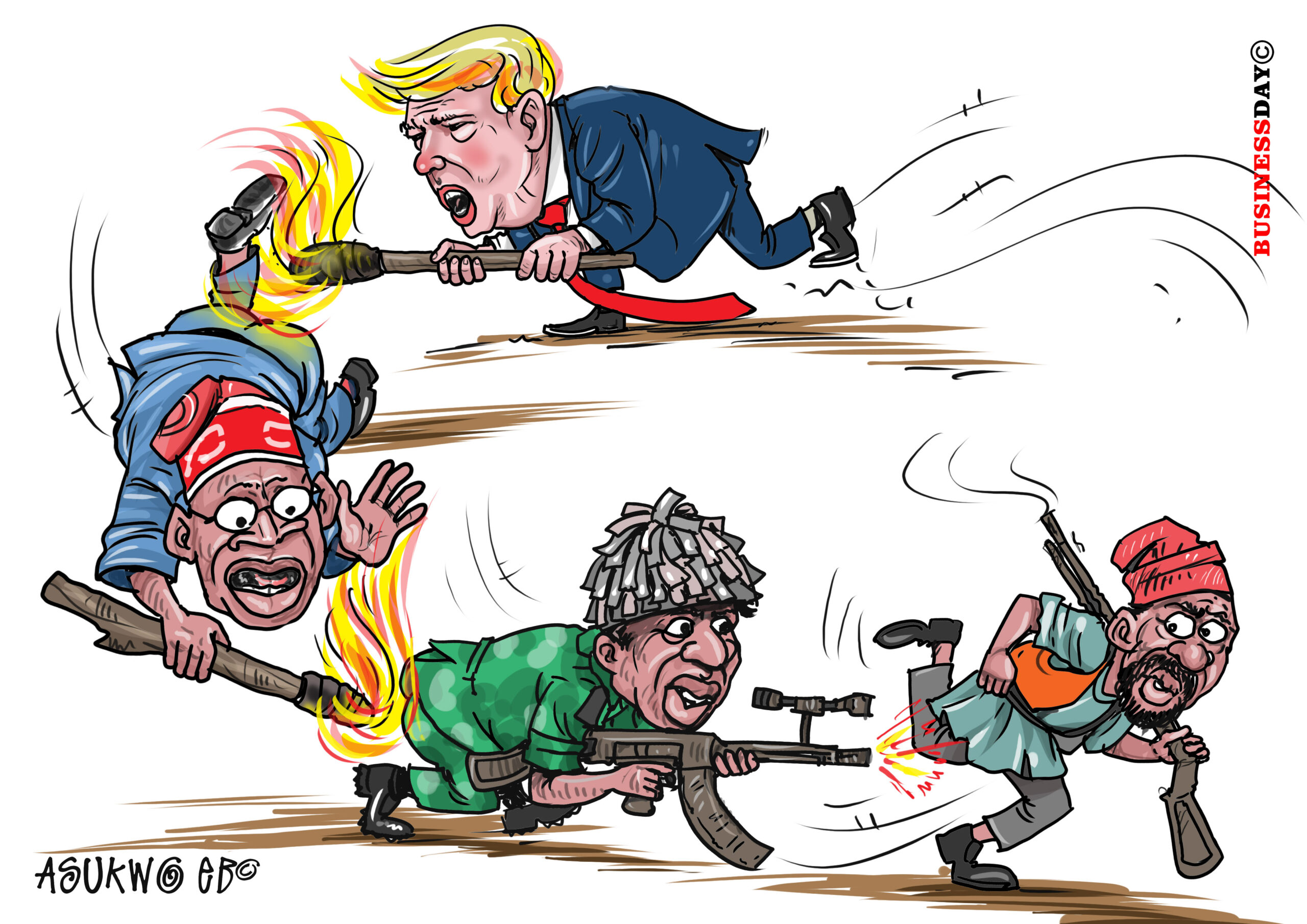

For decades, Nigeria’s insecurity has been framed as a domestic tragedy: insurgents in the North-East, bandits in the North-West, separatist agitations in the South-East, and farmers-herders clashes in the Middle Belt. But in recent months, that familiar story has been recast on a far bigger stage. What was once Nigeria’s internal security headache has morphed into a high-stakes international contest, fought not only in forests and border communities, but in congressional hearing rooms, think tanks and lobbying offices in Washington, D.C.

The turning point came on October 31, 2025, when United States President Donald Trump redesignated Nigeria a Country of Particular Concern (CPC) over alleged violations of religious freedom, specifically claims of a Christian genocide. The CPC label, reserved for the world’s worst offenders, instantly elevated Nigeria’s security crisis from a regional challenge to a global political issue.

From Abuja to Capitol Hill

Nigeria had worn the CPC tag before. In 2020, during Trump’s first term, the country was placed on the list, only for the designation to be lifted months later by President Joe Biden. That reversal angered conservative lawmakers and religious freedom advocates in the US, many of whom argued that violence against Christians in Nigeria was being downplayed for strategic reasons.

The 2025 redesignation reopened old wounds. In Washington, it triggered a flurry of hearings and debates on Capitol Hill. Lawmakers were sharply divided. Some called for sanctions and even military intervention, framing the crisis as state-enabled religious persecution. Others warned against oversimplifying Nigeria’s violence, arguing that criminal gangs, resource conflicts and extremist groups were exploiting weak governance rather than executing a coordinated religious agenda.

Nigeria pushes back

Abuja rejected the framing outright. Nigerian officials insisted that the violence consuming large swathes of the country was not driven by religion but by criminality, competition over land and resources, porous borders and the proliferation of arms across the Sahel.

Read also:¬ÝFake clerics on the prowl as ‚Äòprophecy‚Äô economy booms in Nigeria

Leading the diplomatic counteroffensive was National Security Adviser Nuhu Ribadu, who intensified engagements with US officials, signalling Nigeria’s willingness to cooperate while pushing back against what the government described as a dangerous mischaracterisation. The message was clear: Nigeria was battling terrorists and criminals, not waging war against any faith.

Christmas Day missiles

On Christmas Day, a post from Trump confirmed just how far Nigeria’s insecurity had travelled beyond its borders. The United States had carried out airstrikes on Nigerian soil, targeting terrorist enclaves in the Bauni forest axis of Tangaza Local Government Area in Sokoto State. It was the first confirmed US military strike inside Nigeria.

Questions immediately followed. Where were the missiles launched from? Reports suggested debris fell in Jabo, Tambuwal Local Government Area of Sokoto State, and as far away as Offa in Kwara State. The government said no civilian casualties were recorded. In an interview with The New York Times published days later, President Trump raised the prospect of more strikes.

The operation marked a controversial new chapter in Nigeria’s security partnerships. Just last week, the United States Africa Command announced the delivery of “critical military supplies” to Nigeria, raising sensitive questions about sovereignty, intelligence sharing and the precedent such action sets for the future.

The lobby war

Even as airstrikes and military assistance dominated headlines, another battle was unfolding quietly in Washington’s lobbying corridors.

It was reported last week that Nigeria hired Washington-based consulting firm DCI Group for an initial six-month contract worth $4.5 million, paying $750,000 per month. A similar amount is due should the agreement be renewed for another six months, according to filings with the US Department of Justice.

Under the contract, DCI Group is tasked with briefing US officials on Nigeria’s efforts to protect both Christians and Muslims, countering allegations of genocide and sustaining American support for Nigeria’s counterterrorism campaign in West Africa.

The figures sparked outrage back home. At a time of economic strain, critics questioned why billions of naira were being spent to shape narratives abroad instead of strengthening security at home.

But Nigeria is not lobbying alone.

Biafran separatists and other interest groups have also mounted their own campaigns in Washington, pressing the argument that Christians face systematic persecution in Nigeria. Their budget is modest by comparison, about $66,000, but their objectives are far more radical: sanctions against Nigeria and US recognition of Biafran independence.

A familiar strategy

Nigeria’s turn to foreign lobbyists is hardly unprecedented. Accountability to reports from Premium Times, the administration of former President Muhammadu Buhari in 2018 retained American public relations firms to place opinion pieces favourable to the government in US newspapers. Embassy officials at the time reportedly questioned why public funds were being channelled to lobbyists rather than Nigeria’s diplomatic mission.

Earlier still, in 2013, President Goodluck Jonathan’s government spent thousands of dollars hiring a lobbying firm to arrange media interviews for Nigerian officials on US platforms.

A war beyond the battlefield

Nigeria’s insecurity is no longer judged solely by events in Zamfara villages or Sambisa Forests in Borno. It is being debated in congressional chambers, shaped by advocacy groups, amplified by media narratives and monetised by lobbying firms.

The result is a parallel conflict: one fought with briefing papers instead of bullets, influence instead of insurgents.

As missiles fall in Sokoto and lobbyists clock billable hours in Washington, Nigeria finds itself fighting two wars at once. One is against armed groups destabilising communities at home. The other is against a powerful global narrative that could redefine its sovereignty, partnerships and place in the world.