Nigeria is moving closer to translating global health commitments on cervical cancer into measurable outcomes as the government prepares to align its national strategy with the World Health Organization’s elimination framework by 2026, according to Roberto Taboada, network head for Anglo-West Africa at Roche Diagnostics.

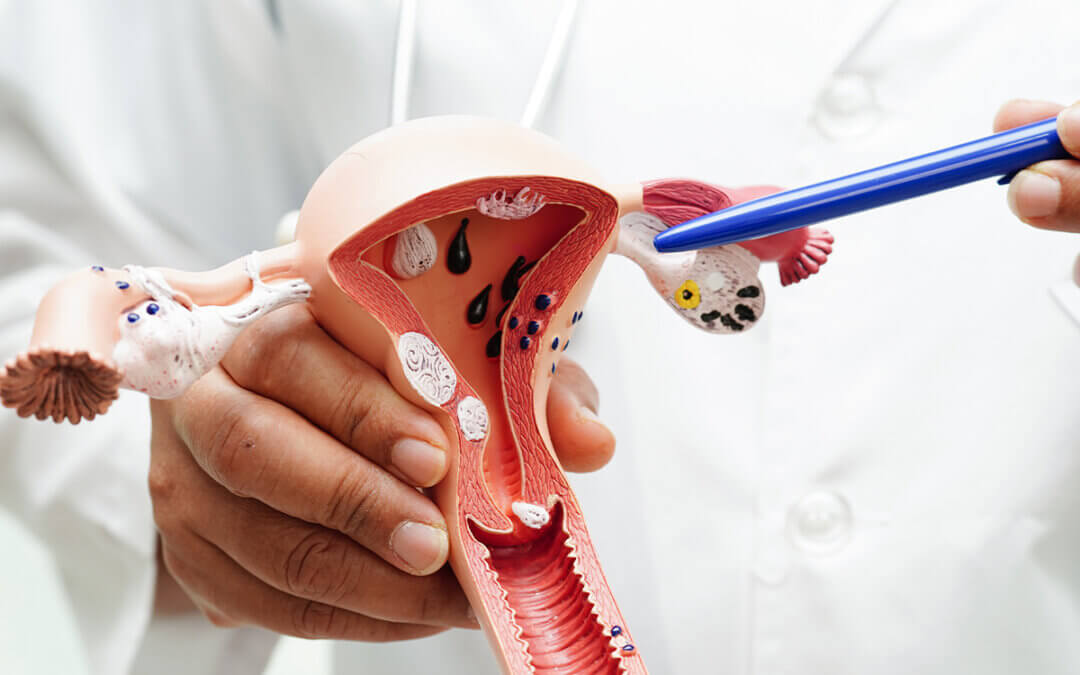

The WHO strategy is built around the so-called 90–70–90 targets to be achieved by 2030: vaccinating 90 percent of girls against human papillomavirus (HPV) by age 15, screening 70 percent of women by ages 35 and 45 using high-performance tests, and ensuring treatment for 90 percent of women diagnosed with pre-cancerous lesions or invasive disease.

“This is a moment where targets can become tangible impact,” Taboada wrote in an opinion piece seen by BusinessDay. “Nigeria has reached a point where political commitment, policy direction and delivery mechanisms are beginning to align.”

Cervical cancer remains one of Nigeria’s most serious but preventable public health challenges. The disease, largely caused by persistent HPV infection, accounts for an estimated 13,700 new cases and more than 7,000 deaths each year. Many women are diagnosed late, increasing mortality and placing heavy economic and social burdens on families.

“For many households, cervical cancer is not an abstract number,” Taboada said. “It arrives late, disrupts livelihoods and reflects gaps in awareness and access to screening.”

Over the past year, Nigeria has stepped up coordination around cervical cancer elimination, setting up a National Taskforce that brings together government agencies, clinicians and private-sector partners. The group is tasked with turning national policy into coordinated action across vaccination, screening and treatment.

Formal national guidelines are intended to give states and implementing partners a consistent framework, helping to standardise care and expand access. Nigeria has also publicly reaffirmed its commitment to the WHO elimination strategy at international health forums, linking domestic policy choices to global accountability.

On prevention, the government began phasing HPV vaccination into routine immunisation in 2023, laying the groundwork for meeting the first pillar of the 90–70–90 targets. Attention is now shifting to screening, where officials see opportunities to build on existing laboratory infrastructure rather than create parallel systems.

Molecular diagnostic platforms already in use across the country, including those supporting HIV programmes, can be adapted for HPV DNA testing, which the WHO recommends as the primary screening method. Integrating cervical cancer screening into these networks could improve efficiency and support broader universal health coverage goals.

“This is about sustainability,” Taboada said. “Nigeria is building on assets it already has, instead of starting from scratch.”

The next phase will include a cervical cancer screening pilot designed to test logistics, workflows and self-collection approaches in real-world settings. Health officials say such pilots are critical to refining implementation before national scale-up.

Alongside infrastructure, authorities are stepping up awareness campaigns to address cultural barriers and encourage women to get screened earlier. Lack of awareness, stigma and personal discomfort continue to limit uptake of screening services.

“Elimination will not happen overnight,” Taboada said. “But with sustained leadership and collaboration, cervical cancer can become a condition that health systems anticipate and prevent, rather than one they confront too late.”

If momentum is maintained, Nigeria’s approach could demonstrate how global health targets can be converted into practical, country-owned solutions — with each vaccination, screening and treatment bringing the country closer to eliminating one of its most preventable cancers.