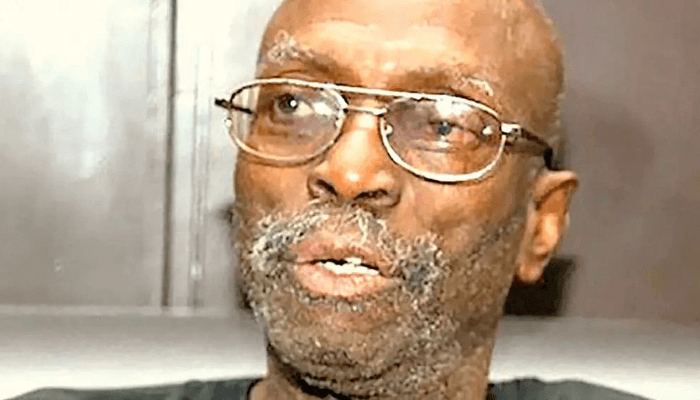

The journey of his life has been, in perspective, as rugged and weather-beaten as his face, which carries as many crags and contours as a sprouting rock in the path of a fast-moving river. Even he admits, when he eventually gets to speak, towards the end of the event, that he was not meant to still be alive, repeating a pitch made earlier in his opening address by the Chairman of the occasion, Dr Yemi Ogunbiyi.

‘…He was not meant to live to be 80 years old…’ Ogunbiyi says with a rather morbid emphasis in his Opening Remarks. The Chairman’s suave good looks and easy elegance stand in sharp contradistinction with the devil-may-care appearance of the celebrant, who has been his friend and hero, he says, since they met at Ibadan Boys High School, where BJ, his instant friend and hero, was one year his elder and was already an anti-establishment stripling who got into trouble endlessly with school authorities.

BJ himself would explain his supposedly tenuous grip on life in more clinical detail, citing statistics. It is lonely being 80, he admits. Most of his siblings and friends are long gone. He misses a particular brother who died more than forty years ago.

On this first Monday in January 2026, a sizable crowd is gathered at the Agip Recital Hall of the MUSON Centre in Lagos. They include literary notables such as Odia Ofiemun, writers and newspaper columnists such as Prof Ropo Sekoni, Sam Omatseye and Kunle Ajibade, and icons of Nigerian journalism such as Dap Olurunfemi. There are former students and associates of the man they all fondly call BJ.

The event is organised by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism to celebrate eight decades of the life of a very remarkable man, who is famous as a Marxist polemicist, an essayist and a critic, and the ultimate universal authority on the body of Wole Soyinka’s literary oeuvre.

During the proceedings, Wole Soyinka himself makes a brief cameo appearance, like a patron saint, before disappearing into the shadows.

The theme of the symposium is ‘Pedagogy, Curriculum and Decolonisation: then and now’.

A former postgraduate student of BJ at Cornell University, Prof Priya Gopal, now Professor of Post-Colonial Studies at the University of Cambridge, is the invited keynote speaker.

After the formalities, Dapo Olorunyomi steps forward to introduce the guest speaker and reveal the topic of her talk, ‘Who is afraid of Decolonisation? Reflections on particular pasts and planetary futures.’

Gopal thanks the organisers for the opportunity to honour her teacher, friend and comrade, Professor Biodun Jeyifo. She emphasises the importance of fostering ‘South to South’ dialogue. She recalls starting her intellectual journey in 1994 when, on advice, she sought out ‘the Nigerian Marxist’ at Cornell University, at a time when post-colonial studies were at their ‘insurgent’ peak.

She shares her memory of presenting the first chapter of her doctoral thesis to BJ. His response is a long-handwritten letter, in which he admonishes her to ‘let the text speak’ and to prioritise engagement with the text over abstract theoretical arguments. This guidance has stayed with her, and she has used it to improve the work of her own students.

She speaks of ‘Arrested Decolonisation’, a term borrowed from BJ. The Cold War has ended, but the condition of arrested decolonisation remains the reality in the Global South. Decolonisation has been diverted, hijacked, or twisted, and has never reached fruition. She recalls the aspirations of African and Asian leaders meeting at the Bandung Conference in 1955, celebrating the lofty promise of imminent independence. The Paris Congress of Writers and Artists in 1956 is a follow-on, featuring the likes of Aime Cesaire, Frantz Fanon, and Richard Wright as they discuss ‘Culture after Empire’.

Already embedded within the apparent unanimity of purpose of former colonial peoples are internal ideological disagreements, such as those between Capitalism and Socialism. The Bandung communique dedicates five of its ten principles to state sovereignty. This focus on ‘flag independence’ becomes widely emblematic of decolonisation. Fanon and Cesaire had wanted decolonisation to be a historic opportunity for radical social and economic transformation and renewal of cultures, instead of nativist elites merely changing hands with colonial powers, which is what has transpired. Their radical vision has been subverted.

Professor Gopal relates arrested decolonisation to contemporary crises in the Global South, such as the ‘seriously genocidal’ conflict in Gaza. She reminds the audience of the words of Cesaire – that the difference between colonisation and decolonisation is ‘not one of degree, but of kind’, and of his question, asked on behalf of future generations of former colonial peoples – ‘What sort of world are you preparing for us?’

Professor Sekoni moderates a panel discussion on Gopal’s lecture. Unsurprisingly, all the discussants are of a ‘progressive’ bent. One avers that decolonisation was arrested at independence because new nations focused on state institutions at the expense of civil society. There is a reference to the socialist-oriented preamble to Nigeria’s 1979 Constitution, which was mischievously deleted, and which called for development and wealth redistribution to proceed pari-passu, creating a social democracy, and not the dubious liberal democracy that has resulted.

Another panel has former students of BJ at the University of Ife speaking on their experience of him and his influence on their lives. One recalls his penchant for lighting a pipe or smoking a Cuban cigar while in intellectual discussion. BJ confesses that the cigars were ‘pilfered’ from Soyinka’s hoard. He tells a joke about how he observed that the ladies in his tutorial class were often giggling as they worked. Illumination came to him one day that he, an indifferent dresser, often left his fly carelessly open.

Through the intellectual burden of his unfulfilled aspirations for Nigeria and the world, in the twilight of his day, Emeritus Professor Biodun Jeyifo – aka BJ, could still laugh heartily at himself.

A vote of thanks, the ritual pumping of hands, and it is time to go.