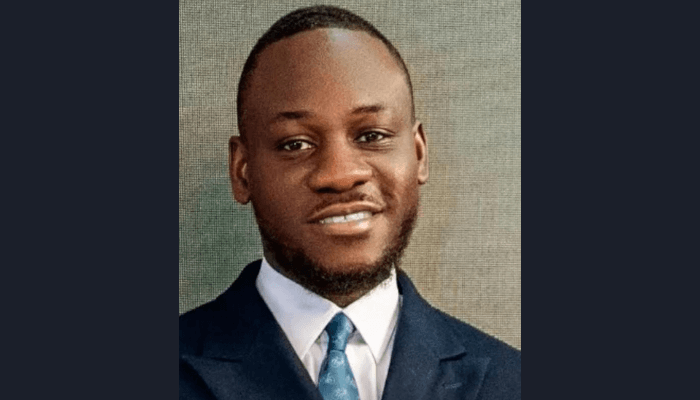

Oluwaseun Ajayi is a globally trained real estate economist and climate-risk scholar recognised for advancing how sustainability and long-term risk are priced in property markets. He is the 2025 winner of the Sarah Sayce Award for Sustainability Research, one of the United Kingdom’s most competitive national research honours in the built environment. In this interview, he speaks on the award and the problem it seeks to solve. He also speaks extensively on climate risk pricing in relation to property valuation, among other salient real estate issues. CHUKA UROKO, Property Editor, reports.

We congratulate you on this prestigious Emeritus Professor Sarah Sayce Award for Sustainability Research 2025. In a nutshell, what does the award mean to you personally and professionally?

Personally, the award is deeply humbling. Professionally, it is a powerful affirmation that rigorous, policy-relevant research still matters, especially research that refuses to treat sustainability as a slogan.

The Sarah Sayce Award is not given for elegant theory alone; it is awarded for work that changes how the property industry thinks, values assets, and manages risk. Winning it tells me that the questions I am asking about climate risk, valuation blind spots, and investor complacency are not only academically sound but urgently necessary.

For me, it also confirms something I have long believed, that sustainability must move from aspiration to calculation. Until risk is priced, it is ignored.

The research that gave you this award is titled ‘Pricing the Unseen.’ In simple terms, what problem does that research seek to solve?

The core problem is that real estate markets globally are sitting on climate risk they cannot see and therefore are not pricing. Most property valuations still look backwards. They rely on past transactions, rental income, and comparable sales. Climate change does not behave that way. It is non-linear, cumulative, and irreversible.

My research asked a simple but uncomfortable question: If climate risk were properly priced today, how many assets would already look overvalued? Using the UK’s flagship flood-adaptation programme (the Thames Estuary 2100 Plan), I showed that even where world-class infrastructure exists, markets still underestimate downside risk. In some scenarios, portfolios face hidden losses of up to 25 percent over time. That is not an environmental problem. That is a financial stability problem.

Your research was conducted in the UK. Why should policymakers and investors in Nigeria, particularly Lagos, care about such research?

Because Lagos is already living the future that London is still preparing for. Areas such as Lekki Phase 1, Victoria Island, Ikoyi, Ajah, and parts of Badagry now flood not as anomalies, but as recurring market events despite flagship interventions like Eko Atlantic and the Lagos State Climate Action Plan. My UK research shows that even under the Thames Estuary 2100 Plan, one of the world’s most sophisticated flood-adaptation strategies, property markets still materially underprice long-term climate risk.

If mispricing persists in London, with its regulatory discipline and insurance depth, then Lagos, where assets are built on reclaimed land, informal development encroaches on flood plains, and climate risk is absent from valuation standards, is facing a far more severe valuation distortion. The danger for Nigeria is not climate change itself, but delayed recognition. When repricing eventually arrives in Lagos, it will not be incremental; it will be abrupt, capital-destructive, and socially destabilising.

In light of your explanation, what exactly do you suggest the Lagos State government should be doing differently right now?

With respect, I would prioritise three actions. First, Lagos should formally embed climate-adjusted valuation into professional and regulatory practice. Currently, property values remain stable despite increasing exposure. Flood risk, heat stress, drainage capacity, and infrastructure reliability should be treated as measurable financial inputs, rather than qualitative commentary. This is not about discouraging investment; it is about protecting the integrity of the market and the long-term tax base of the state.

Second, adaptation infrastructure must be communicated and governed as a financial commitment, not only an engineering response. Drainage projects, shoreline protection and regeneration schemes preserve value only when markets trust their durability. That trust is built through legal permanence, transparent delivery timelines and clear alignment with planning controls, insurance practice and development finance frameworks.

Third, I would recommend the creation of a single, authoritative Lagos Climate Risk Map (LagCRiM) explicitly linked to property taxation, mortgage underwriting and insurance pricing. When public authorities, banks, valuers and insurers work from the same risk architecture, capital reallocates efficiently without coercion, and resilience becomes a market outcome rather than a subsidy. These steps would not make Lagos less investable. They would make it more credible, more resilient and more competitive in a climate-constrained global economy.

There are still arguments about climate risk. For instance, some developers argue that pricing climate risk will scare investors away. What do you think?

That argument misunderstands capital. Investors are not afraid of risk, but they are afraid of unknown risk. What truly scares capital is sudden repricing, especially when insurance is withdrawn overnight, when assets become stranded, and when infrastructure fails without warning. What I have observed is that transparent risk pricing does not kill markets. It stabilises them. Therefore, the most attractive cities of the future will not be those that deny climate risk, but those that price it honestly and manage it intelligently.

Your research used advanced tools such as Climate Value-at-Risk and machine learning. Can African institutions realistically adopt these methods?

Yes, and more quickly than many assume. Africa does not need to replicate Western systems line by line; it can leapfrog them. Nigeria already possesses the critical inputs, including transaction-level property data, satellite-derived flood and heat data, climate projections, and rapidly improving digital infrastructure.

The constraint is not in technology; it is institutional coordination. What is required is deliberate collaboration between universities, government agencies, regulatory bodies, banks, and professional bodies (Nigerian Institution of Estate Surveyors and Valuers and the Estate Surveyor and Valuers Registration Board of Nigeria) so that these tools are standardised, trusted, and embedded in decision-making.

Climate Value-at-Risk and machine learning are simply structured ways of asking better questions of data we already have. This is where Africa can lead by integrating climate intelligence directly into urban growth and investment frameworks now, rather than retrofitting it after decades of costly mispricing.

Almost always, awards have impact on recipients. In your own case, how does this award change your next steps?

It sharpens my responsibility. My focus is now threefold, including policy advisory work, especially with governments and regulators in climate-exposed economies; capacity building, which entails training valuers, planners, and investment analysts across Africa; and applied research platforms aimed at turning climate risk into decision tools, rather than just journal articles. This work has the potential to sit on the desks of commissioners, ministers, pension funds, and university vice-chancellors, not only in libraries.

Serious-minded people are excited by success. What, therefore, is your message to the youth, especially young African scholars and professionals watching this achievement?

Do not chase relevance by being loud, but chase relevance by being useful. The world is changing faster than our institutions, and Africa needs thinkers who can translate complexity into action, who are comfortable at the intersection of data, policy, finance and society.

I say this with deep gratitude to God, who orders steps beyond our planning, and with profound acknowledgement of my biological and academic fathers, Emeritus Professor Cyril Ayodele Ajayi & Professor Omokolade Akinsomi, whose lives as scholars taught me that excellence is sustained and not performed. This award affirms that African scholarship, when rigorous, grounded and principled, can shape global conversations. And truly, we are only just beginning.