Coming off the back of a glamorous ‘Detty December’ celebration in Lagos, which reached its apogee in the Eyo Festival, it was curious to speculate about how the complexity and spiritual synthesis of the culture of the Yoruba might appear to people from other cultures. A post that has been circulating on the internet in the past few days wonders with awe about people who could celebrate Christmas on a Thursday, go to Jumaat prayers on Friday, dance with ‘Adimu’, ‘Ologede’, ‘Oniko’ and other ‘Orisha Eyo’ on Saturday, and, yes, go to Church on Sunday.

The issue of the spiritual life of the Yoruba has long been a subject of speculation and study by experts in mental and sociological sciences.

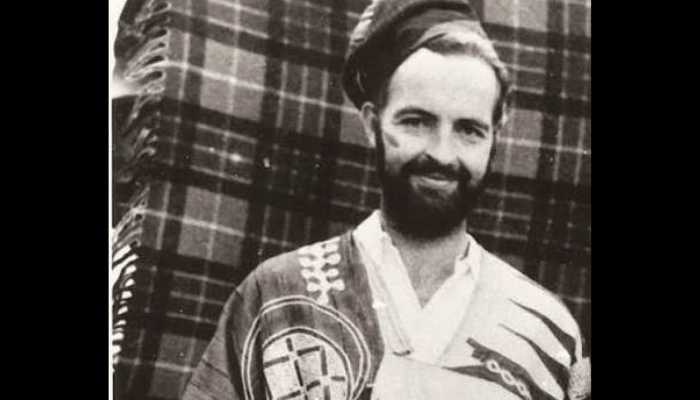

The story of Dr Raymond Prince makes for interesting discussion. He was born in Ontario, Canada, in 1925. He studied Psychiatry and obtained a Fellowship of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada in 1955. In 1957, he responded to an advert in the British Medical Journal for a ‘Specialist Alienist’ – the old description for a psychiatrist, who was willing to go out to Western Nigeria to work. He was offered the job by the government of Western Region.

Thirty-two-year-old Dr Prince arrived at Aro Psychiatric Hospital, Nigeria’s first mental hospital, shortly after his employment. He was a restless and adventurous youth who was trying to find himself, and to discover his passion. Born of Baptist parents, he had renounced his faith along the way. He retained a healthy curiosity about spiritual matters and was very interested in the influence of culture and traditional beliefs on the manifestation of mental illness among people of non-Western societies.

As he settled into the warm atmosphere of Abeokuta, he became fascinated with the Yoruba people. This was during a period when Thomas Adeoye Lambo, the first Western trained Nigerian psychiatrist, who had been appointed as the Medical Superintendent of the facility, was away to the United Kingdom on an assignment from the government of Western Nigeria to research into the worrying frequency with which students on scholarship in foreign universities were developing signs of mental illness.

The nineteen months that Dr Prince spent in Abeokuta and its environs were to determine the direction of his life and career irrevocably. His legacy in the Mental Health profession includes the enunciation of a diagnostic category known as ‘Brain Fag Syndrome’ which describes a common set of physical and psychological symptoms he observed in local students, which he held to be a culture-bound illness.

Prince’s most important achievement ultimately lay in his efforts to understand the Yoruba mind in sickness and in health. He warmed his way into the affections of the local people and was very interested in finding out their world view and the belief system that helped them to interact with the world around them. He began to visit traditional medicine practitioners in Abeokuta and surrounding areas, travelling as far afield as Okun Owa near Ijebu Ode, where he lived for two weeks with a native doctor, Chief Jimoh Adetona, who was renowned for his treatment of the mentally ill. Strangely, for people who were notorious for shrouding their knowledge and practices in mystery, they opened up to him, and he was able to learn a lot about the ingrained beliefs that provided guard-rails to their religious lives and their efforts to heal the sick. He learned, and wrote, about the role of the spoken Word (Ọ̀rọ̀) in Yoruba culture. He learned the distinction between a ‘Babalawo’, a priest who relied on divination with Ifa, and Onisegun, who relied mostly on herbs. He learned that even the preparation of herbs often involved some rituals and the uttering of some ‘power-Words’. He learned about the use of Rauwolfia alkaloids – containing Reserpine, a drug known in the West, by some herbalists. He learned about curses and invocations, which could be used for both good and bad purposes by the same practitioners. He connected this back with the experience of many of the patients he saw at Aro, who attributed their illnesses to being ‘cursed’.

Later, as his reputation grew, he would play a role in the collaboration between Lambo and the Canadian Alexander Leighton and his team to carry out the so-called Cornell-Aro studies, the first major cross-cultural epidemiological study of mental illness symptoms undertaken in Africa. This resulted in a publication titled ‘Psychiatric Disorder among the Yoruba’.

Many of Prince’s later academic achievements were derived from lines of thinking started during his stay in Abeokuta. He made a genuine effort to understand the experience of non-European people from within, and did not attribute things he did not understand to a diminished capacity on the part of Africans to experience higher mental functions, as some colonial psychiatrists of the past had done. His fascination with the Yoruba mind, his emphasis on the importance of Ọ́rọ̀ and his discernment of the interpolation of good and evil in Yoruba philosophy made it possible for him to understand why a few Babalawo seemed sometimes to act without querying the right or wrong in what their client was requesting of them. It also opened his eyes to how the people saw an affinity with the Abrahamic religions of Christianity and Islam, and mixed them with culture in a seamless syncretism.

Prince died in 2012. He had lived the life he chose. His ‘Brain Fag syndrome’ may have lost most of its relevance in the present day, but he introduced concepts such as Culture Bound Syndromes and Transcultural Psychiatry which are ongoing areas of study. He made mental health less Eurocentric. Finally, his insistence that mental health workers should be trained locally is a respectful nod to what he learned in Nigeria, and how he tried, with only partial success, to understand the Yoruba mind in sickness and in health.