As inequality widens across both developing and advanced economies, policymakers are increasingly questioning whether traditional growth models are delivering meaningful inclusion. Despite global commitments under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to reduce poverty, expand decent work, and close inequality gaps, progress remains uneven.

At the heart of the challenge is a fundamental question: how can households and small businesses access financial systems that genuinely improve stability, resilience, and opportunity rather than expand access on paper?

In this interview, Luqmon Oladele, an applied economist and development finance professional and Fellow of the Institute of Management Consultant with experience across Nigeria and the United States, shares insights from years of hands-on program work, research, and economic analysis focused on household empowerment and small-business resilience. BusinessDay’s Chinwe Michael brings excerpts.

When we talk about inequality globally, what do you see as the most persistent economic barrier today?

One of the most persistent barriers is financial fragility. Across countries, households and small businesses often operate without buffers. A single shock, such as an illness, inflation, policy change, or supply disruption, can undo years of progress.

Inequality is not just about income levels, it’s about exposure to risk and the absence of tools to manage that risk. Development finance matters because it determines whether people can stabilize income, smooth consumption, and sustain productive activity when shocks occur.

The SDGs emphasise financial inclusion, decent work, and poverty reduction. Why has progress been slower than expected?

Inclusion has too often been treated as access rather than outcomes. Opening bank accounts or expanding credit does not automatically translate into resilience.

The real test is whether households experience more stable incomes and whether small businesses can survive, grow, and create jobs. Many programs underestimate how fragile enterprise cash flows are or how sensitive households are to inflation and policy uncertainty. Without careful design and evaluation, well-intended interventions fall short.

How do inequality dynamics differ between developing and developed economies?

The contexts differ, but the underlying structure is surprisingly similar. In developing economies, exclusion is often driven by informality and weak financial infrastructure. In developed economies, exclusion is more subtle, with high transaction costs, credit constraints, or institutional barriers.

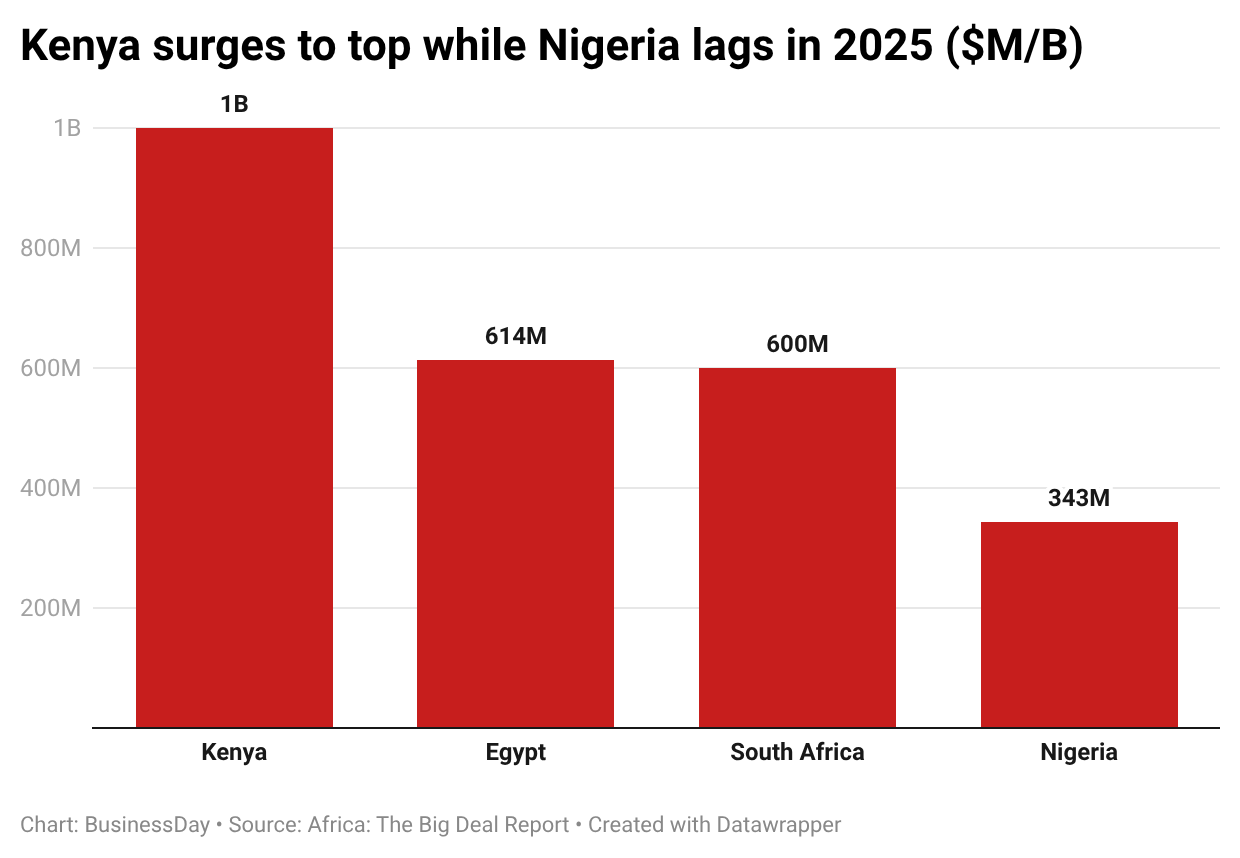

In both settings, small businesses struggle to access affordable finance, and households face income volatility. That’s why lessons from financial inclusion work in places like Nigeria are increasingly relevant in advanced economies as well.

Small businesses are often described as engines of inclusive growth. What makes them so vulnerable?

Small businesses operate on a tight margin. They depend heavily on short-term cash flow and are highly exposed to shocks in demand, prices, and policy.

Without appropriate financial tools—working capital finance, savings mechanisms, or risk-sharing instruments—many cannot absorb disruptions. Supporting SMEs is not just about growth; it’s about resilience. When small businesses fail, households lose income and communities lose economic anchors.

From your experience, what distinguishes effective development finance programs from ineffective ones?

Effective programs are evidence-driven and adaptive. They recognize local constraints and design financial products around real business cycles and household behavior.

They also prioritize financial discipline, clear reporting, accountability, and sustainability. Programs that focus only on scale or disbursement often miss these fundamentals. My work consistently emphasises evaluation, asking whether an intervention improves stability, not just participation.

How should development finance evolve to better address inequality?

It must move closer to households and enterprises. That means designing finance that aligns with income patterns, supports gradual growth, and helps build buffers over time.

It also means improving data and evaluation so decisions are based on outcomes rather than assumptions. Development finance should be practical, accountable, and responsive, not abstract.

What role do professionals like you play in shaping this evolution?

Our role is to bridge analysis and implementation. Applied economists and development finance professionals must translate data into actionable insights that improve program design.

Over the past six years, my work—across financial inclusion initiatives in Nigeria, development finance programs, academic research, and nonprofit engagement in the U.S.—has focused on building that bridge. Addressing inequality is not a single intervention; it’s sustained, evidence-based work across systems.

Finally, are you optimistic about the future of inclusive economic development?

Cautiously optimistic. The challenges are real, but so is the growing recognition that inclusive growth requires intentional financial design.

When households and small businesses are empowered with the right tools, the impact multiplies across communities. That belief has guided my career, and it continues to shape how I engage with development finance globally.