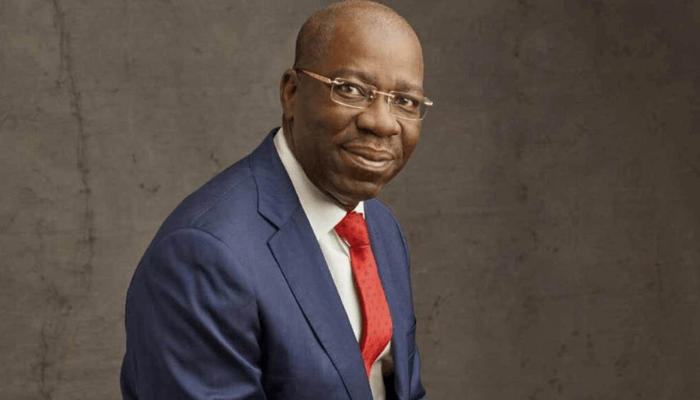

In 2021, a vision was articulated with clarity and ambition. Former Edo State Governor Godwin Obaseki stood before international stakeholders and outlined a plan to transform Benin City into a “thriving modern cultural district”. The centrepiece was to be the Edo Museum of West African Art (MOWAA), designed not merely as a repository for returned artefacts but as an economic catalyst, a creative hub to generate “real jobs and opportunities” for Nigeria’s youth. It was a forward-looking blueprint to leverage heritage for sustainable, non-oil growth.

Today, that vision lies in tatters, a casualty of the very governance failures it sought to transcend. The museum project has become a political battlefield, emblematic of a destructive pattern where institutional conflict and short-term political gain systematically dismantle long-term economic potential.

The unravelling was spectacular. Last month, as 250 Nigerian and international dignitaries gathered for a preview of MOWAA, protesters stormed the building, forcing its closure and the evacuation of guests, including foreign diplomats. While the museum’s management decried the actions of “hooligans”, its critics, aligned with the current All Progressives Congress (APC) government, framed the protest as righteous indignation against an elite “heist”. Within a day, Governor Monday Okpebholo announced the revocation of the museum’s land title.

This episode was not about heritage management; it was raw political theatre. The project became a proxy in the bitter feud between the former PDP administration and the current APC one. Governor Okpebholo’s move, celebrated by his allies as restoring land to its “rightful purpose”, sent a chilling message far beyond the cultural sector: in Edo State, major projects and legal agreements are subject to abrupt reversal when political winds change.

Alarmingly, this is not an isolated case. A nearly identical script played out with Presco Plc, Nigeria’s largest palm oil producer and a critical agro-industrial asset in Edo State. In late November, a public notice surfaced, bearing the governor’s signature and revoking Presco’s Certificate of Occupancy for 13,545 hectares of land, citing “overriding public interest”. The potential economic fallout was staggering, threatening a company that had just attracted a $100 million foreign investment from Belgian firm SIAT.

“It revealed that the most critical legal assurance of land tenure can be weaponised overnight and then retracted just as quickly, all within a fog of political “misunderstanding”.”

Facing a backlash, the state government swiftly performed a U-turn. The Commissioner for Information denied the revocation was true. Governor Okpebholo himself assured Presco’s management, “I am an investor myself. I cannot be the one sending investors away.” He dismissed the controversy as a “misunderstanding” someone had tried to politicise.

But the damage was done. The initial revocation notice was not a secret memo; it was a public declaration. For any investor, domestic or foreign, the episode demonstrated a terrifying volatility. It revealed that the most critical legal assurance of land tenure can be weaponised overnight and then retracted just as quickly, all within a fog of political “misunderstanding”. This is the antithesis of the stable, predictable environment that capital requires.

The tragedy is that this political score-settling directly sabotages the national economic priorities that leaders claim to champion. Vice President Kashim Shettima has assured global investors that “Nigeria has exited its phase of economic instability,” citing improved fiscal metrics and a commitment to reform. He emphasises that no economy can thrive where insecurity, including policy insecurity, undermines enterprise.

Yet, the events in Edo State embody the very instability the Vice President decries. They showcase how personal vendettas and institutional clashes between state governments, traditional authorities, and federal bodies create a landscape where long-term planning is impossible. When a governor can, in one breath, celebrate a historic $100 million investment and, in another, issue a notice that jeopardises the land underpinning it, he declares that contract sanctity is negotiable.

The real victims are not the politicians. They are the young artisans of Igun Street, whose hoped-for renaissance through museum-linked tourism has been rendered moot. They are the workers and communities whose prosperity is tied to stable agro-industrial giants like Presco. They are the citizens denied the jobs, skills, and revenue that these now-paralysed projects promised.

Edo State’s turmoil is a stark lesson for all of Nigeria. Foreign direct investment is not won by press conferences announcing budget increases for agriculture or security. It is won by demonstrating that the rules of the game are fair, consistent, and enforceable beyond the next election cycle. By choosing revocation over collaboration and political vengeance over policy continuity, Edo’s current leadership has done more than cancel a museum or scare a corporation. It has written a cautionary tale, signalling to the world that in this part of Nigeria, the greatest investment risk is not market forces, but governance itself. Until this changes, the country’s economic potential will remain perpetually held hostage by its politics.

Nwanze is a partner at SBM Intelligence.