Nigeria’s decision to tighten cash-withdrawal limits has triggered fresh debate across markets, boardrooms and the informal economy. Under the new CBN rules taking effect in January 2026, individuals may withdraw up to ₦500,000 weekly and corporates up to ₦5 million across all channels, with higher withdrawals attracting regulated fees. To some, this marks a necessary step toward financial transparency, anti-money laundering compliance and digital transformation. To others, it threatens to destabilise the informal sector that remains the backbone of Nigeria’s commerce. Both views capture parts of the truth, but the deeper story is that Nigeria is entering a quiet monetary revolution—one that could reshape how millions transact, save and build businesses.

“Fintechs, supermarkets, organised retail, platform-based transport operators and SMEs with digital records will benefit most from improved traceability and reduced cash-handling risks.”

The cultural and economic weight of cash

Cash in Nigeria is not merely a payment instrument; it is a cultural, psychological and economic anchor. It works when networks fail, when electricity collapses, and when digital literacy is limited. This matters in a country where the informal economy accounts for roughly 65 percent of GDP and more than 90 percent of employment, according to ILO data. From Balogun to Onitsha and Kano to Uyo, cash is the operating system of everyday life. Against this backdrop, tighter cash limits are far more than regulatory adjustments—they disrupt habits that have shaped economic behaviour for decades.

Read also:¬ÝNigeria‚Äôs monetary reforms: What the CBN has done‚ÄîAnd what comes next in 2026

Formalisation pressure in a cash-heavy economy

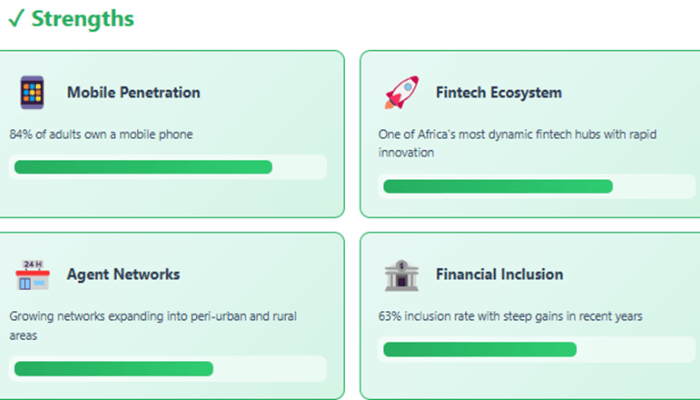

While Nigeria remains dominated by cash transactions, financial inclusion has improved significantly. World Bank data shows that about 63 percent of adults now have an account, and more than half have carried out a digital transaction. This shift has accelerated alongside Nigeria’s removal from the FATF grey list in October 2025—a corrective step after deficiencies in AML/CFT monitoring placed Nigeria in the high-risk category in 2023, a move that studies suggest can reduce capital inflows by up to 7.6 percent of GDP. Tightening cash-withdrawal limits is part of the post-grey-list reform architecture. It strengthens traceability, reduces illicit cash movement and signals a commitment to financial discipline and transparency.

Digitisation and the promise of visibility

For businesses, especially SMEs, reduced cash reliance can bring tangible gains. Digital transactions make record-keeping easier, enable access to credit scoring and increase participation in formal value chains. Nigeria’s fintech ecosystem is already demonstrating what is possible. PalmPay, for instance, reports about 35 million registered users and more than one million business clients supported by an extensive agent network bridging cash-heavy communities with digital platforms. With 84 percent of adults owning a mobile phone, the infrastructure for a more cash-lite economy is strengthening. But digitisation also needs reliability, trust and affordability—areas where Nigeria still faces gaps.

The vulnerability of the informal backbone

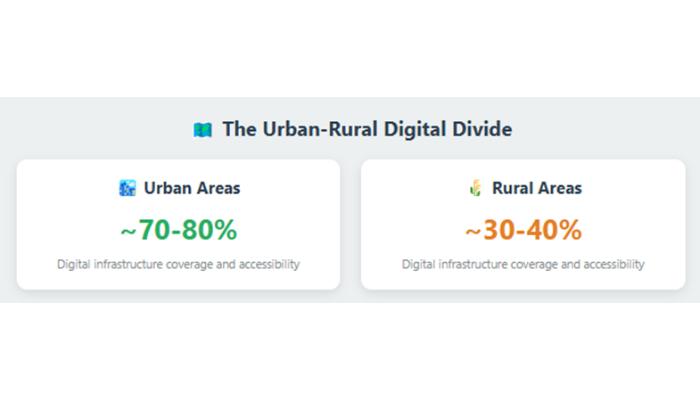

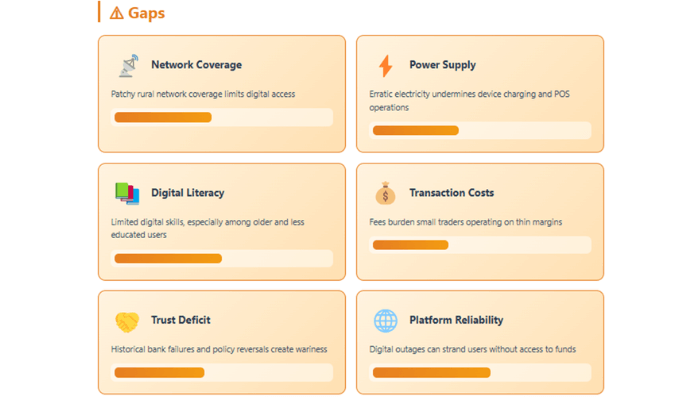

The informal economy is vast, fragile and highly sensitive to liquidity constraints. Micro-entrepreneurs depend on daily cash turnover for restocking, transport, wage payments and household needs. A sudden or poorly sequenced reduction in cash availability can freeze trade in many communities. Rural areas face even greater risks. Sparse banking infrastructure, weak network coverage and erratic power supply mean that digital adoption cannot simply be mandated. A liquidity shock in such environments can quickly cascade into reduced food availability, slower trade and growing vulnerability. Digital transactions also involve fees that can erode the razor-thin margins of small traders. And trust remains a major barrier: memories of bank failures, sudden policy changes and restrictions still shape attitudes toward formal finance.

A young, connected nation at an inflection point

Despite these risks, Nigeria stands at a pivotal moment. Its youthful population, fast-growing fintech sector and expanding agent networks create a foundation for long-term digital transformation. Cash-withdrawal limits, when properly sequenced, could accelerate this shift toward a more transparent, connected and efficient economy. Sequencing, however, will be decisive. The policy must align with expanded agent networks, reliable digital platforms, reduced microtransaction fees and targeted exemptions for vulnerable groups such as rural farmers or micro-retailers. Poor sequencing risks widening inequality and triggering backlash.

Winners, losers and the shape of tomorrow’s marketplace

Fintechs, supermarkets, organised retail, platform-based transport operators and SMEs with digital records will benefit most from improved traceability and reduced cash-handling risks. Micro-enterprises with limited digital readiness and rural traders and workers without social protection face higher short-term adjustment costs. If reforms deepen inequality or disrupt livelihoods, resistance will rise—slowing formalisation and weakening trust in institutions.

Read also:¬ÝDoes the CBN‚Äôs decision to retain the monetary policy rate support price stability?

A quiet revolution in motion

Nigeria now stands where Kenya was before M-Pesa’s rise and where India stood before its gradual formalisation drive. In both countries, success required patience, recalibration and inclusive governance. Cash will remain important in Nigeria—culturally, economically and practically. But its dominance will fade as digital rails expand and policy nudges accumulate. If executed well, this transition could unlock new access to credit, strengthen tax collection, support business growth and enhance economic resilience. It would also reinforce Nigeria’s credibility globally following its exit from the FATF grey list. If mishandled, it could strain livelihoods, slow commerce and deepen distrust of financial institutions. Nigeria has chosen the path of reform. The real test now is whether it can deliver a transition that is disciplined, inclusive and aligned with the realities of the people who rely on cash the most.

Dr. Oluyemi Adeosun, Chief Economist, BusinessDay