Nationwide concerns have surfaced over whether money sent home for family support, gifts, or personal projects could attract income tax, as stricter reporting and enforcement measures take hold.

‚ÄúPersonal transfers such as family remittances, gifts, refunds (example flight tickets) are not, only income earned is subject to tax,‚ÄĚ said Taiwo Oyedele, Chairman of the Presidential Committee on Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms.

According to Section 3 of the National Tax Act (NTA) ‚ÄúIncome tax shall be determined in accordance with the provisions of this Act, and imposed on the¬† (a) profits or gains of any company or enterprise; (b) income of any individual or family; and (c) income arising, accruing or due to a trustee, or an estate.‚ÄĚ

The statute makes clear that tax is imposed on profits or gains and income of individuals and families, and provides a long list of sources that qualify as taxable receipts.

‚ÄúIncome, profits or gains of a person accruing in or derived from Nigeria, including (a) profits or gains from any trade, business, profession or vocation ‚Ķ (d) fees, dues, allowances, or any remuneration for services rendered ‚Ķ (j) profits or gains from transactions in digital or virtual assets; and (k) any other income, profit or gain not falling within the preceding categories.‚ÄĚ

By contrast, capital receipts such as gifts, personal remittances, or family support where no service is rendered do not qualify as taxable income, experts note. This distinction is critical for the millions of Nigerians relying on money sent from the diaspora.

Read also: Tax laws do not permit direct bank debits, Oyedele says

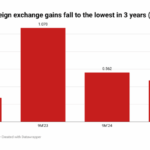

Nigeria remains one of Africa’s largest recipients of diaspora inflows. Sharon Dimanche, IOM’s Chief of Mission in Nigeria has disclosed that Nigeria has received over $20 billion in remittances in 2024 from Nigerians in the diaspora, making such transfers a critical source of household support and foreign exchange.

The scale of these inflows has increased fears and panic among citizens that recipients could be automatically flagged for tax purposes, especially as banks and other financial institutions face stricter reporting obligations.

Oyedele, however, stressed that Nigeria operates a self-assessment tax system, not an automatic taxation of inflows.

‚ÄúEvery individual is required to self-report their income and pay tax where applicable,‚ÄĚ he said, adding that tax authorities focus on earned income, not legitimate personal transfers.

Despite the clarity, some experts warn that enforcement challenges remain. Chukwuemerie Kanu, audit supervisor at Grant Thornton, noted in a LinkedIn post that Nigeria’s weak documentation culture could create room for discretionary enforcement.

‚ÄúIn Nigeria, where record-keeping is often poor, this could lead to harassment, with tax officers pressuring citizens to ‚Äėsettle‚Äô cases informally,‚ÄĚ he said.

Funds labelled as ‚Äúfamily support‚ÄĚ or ‚Äúproject money‚ÄĚ could attract scrutiny if evidence suggests they represent payment for services, business income, or recurring commercial activity.

While personal transfers remain non-taxable, inadequate documentation can lead to disputes, delays in processing, or even temporary account freezes flagged by banks.

Economists warn that mismanaged enforcement could inadvertently discourage diaspora contributions, which are a lifeline for millions of households and a crucial foreign exchange source. Clear communication, legal awareness, and consistent documentation will be key to balancing compliance with citizen confidence.

For most Nigerians receiving genuine gifts or personal remittances, the law is clear: tax applies to income earned, not to personal transfers. Proper documentation and transparency, however, remain critical to avoid disputes with tax authorities.