It did not happen in Africa. It did not begin with Nigeria. Yet the early hours of 24 February 2022 demonstrated how modern markets react when security collapses. As Russian forces crossed into Ukraine, European stock indices fell between 3 percent and 5 percent within hours.

Brent crude prices surged past $100 per barrel, and defence stocks climbed sharply. The economic lesson was immediate: security events, even thousands of kilometres away, can trigger instant financial responses.

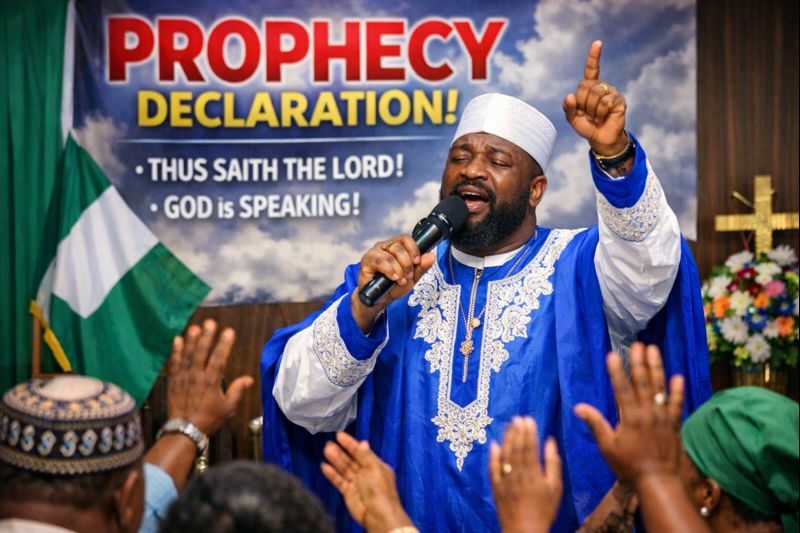

“For a country heavily reliant on imports, these shocks translate into higher domestic prices, rising logistics costs, and elevated fiscal pressure.”

Nigeria is not at war, yet its persistent insecurity increasingly produces economic effects that markets can no longer ignore.

For Africa’s most populous economy, the lesson is clear. Security crises are not just political or humanitarian challenges. They are economic shocks that influence markets, investor decisions, and national balance sheets. The longer insecurity persists, the higher the cost to investment, productivity, and economic growth.

Markets adjust to insecurity quickly, whether through global shocks or local violence. When the First World War began in 1914, the London Stock Exchange closed for nearly five months. Investors responded not to troop movements but to the fear that governments could no longer guarantee the safe movement of capital.

Today, the speed of market reaction is faster, but the logic is the same: when security falters, risk repricing happens rapidly and indiscriminately.

Read also: Nigeria’s 65% skills gap threatens economic growth amid global labour shifts- Report

Nigeria’s insecurity as an economic variable

Nigeria is not at war, yet chronic insecurity imposes significant economic costs. ACLED and the Nigeria Security Tracker estimate thousands of conflict-related deaths annually, stretching from Borno to Zamfara and across Plateau and Benue.

These incidents rarely create dramatic swings in the stock market, but they impose a continuous drag on investment, asset valuation, and corporate planning.

Traders in Lagos quietly adjust pricing models, pension funds reduce exposure to high-risk regions, and multinational firms revise project timelines. One logistics operator in Kaduna described the situation simply: “Every route is a calculation.”

Trucks reroute to avoid flashpoints, fuel costs rise, and delivery schedules slip. These micro-adjustments accumulate into macroeconomic friction.

Mucahid Durmaz, West Africa senior analyst at Verisk Maplecroft, has emphasised that “Nigeria’s insecurity influences business decisions long before it appears in macroeconomic data.” Logistics disruptions and staff safety concerns are already shaping corporate strategy across the northern corridor.

Rising costs and shifts in investment

During the height of Boko Haram attacks in 2014 and 2015, banking and consumer stocks experienced temporary declines. Between 2021 and 2023, as banditry expanded, agribusinesses reported higher security and transportation costs.

Cargo insurers increased premiums on northern routes. Individually, these effects may seem small, but collectively they narrow margins, weaken earnings, and postpone investment.

Food prices highlight the economic impact. The National Bureau of Statistics recorded food inflation at 33.93 percent in December 2023. After CPI rebasing in 2024, it fell to 26.08 percent in January 2025, 23.51 percent in February, and 13.12 percent in October.

Violence reduces production, complicates transport, and drives prices up. Zainab Usman, director of the Africa Programme at the Carnegie Endowment, argues that Nigeria’s difficulty in unlocking agricultural and industrial growth is inseparable from its security challenges.

Read also: Economic Growth in Nigeria: Adewole Adebayo offers alternative perspective

Global shocks amplify domestic fragility

External shocks compound Nigeria’s internal security challenges. European natural gas prices increased nearly fivefold between early 2021 and mid-2022 as the Ukraine war intensified.

Shipping disruptions in the Red Sea in 2023 and 2024 forced vessels to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope, doubling container shipping costs.

For a country heavily reliant on imports, these shocks translate into higher domestic prices, rising logistics costs, and elevated fiscal pressure.

Investor confidence in the balance

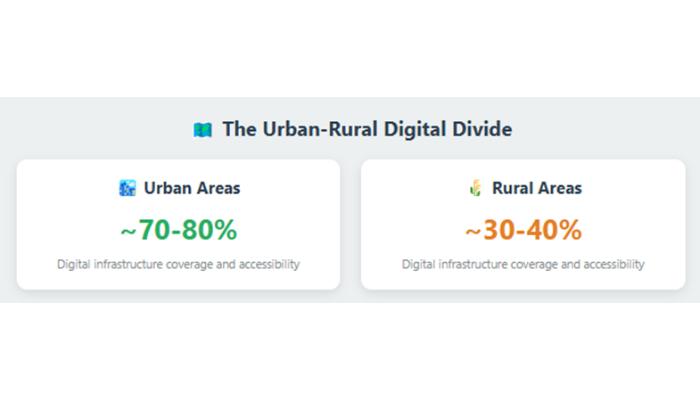

Foreign capital inflows illustrate the impact. Nigeria attracted $21 billion in capital importation in 2014, but by 2023, this had fallen to below $4 billion.

Charles Robertson, head of macro strategy at FIM Partners, explains, “Investors view Nigeria through a combined lens of exchange rate uncertainty and physical security risk. Even strong reform commitments struggle to outweigh unresolved instability.”

Telecom operators invest heavily in securing towers, pension funds prefer safer states, and oil producers struggle with pipeline sabotage, keeping output below potential.

Insecurity can reshape economies

History shows that insecurity can create new industries. The Second World War accelerated aerospace manufacturing, the Cold War drove computing, and after September 11, cybersecurity expanded globally.

Nigeria is experiencing a similar shift: more than 800,000 people work in private security, while logistics and telecom firms invest in surveillance, tracking systems, and fortified transport. With proper regulation, this sector could become formal and investable.

The high cost of delay

Nigeria operates in a world where geopolitical shocks travel quickly. Shipping disruptions affect domestic inflation. Sahel instability threatens national security. Conflicts in Europe and the Middle East alter capital flows. Security is not optional; it underpins investor confidence, borrowing costs, productivity, and long-term development.

Markets have already priced Nigeria’s insecurity. The question is how deeply and for how long. Each year of unresolved insecurity increases the economic cost. Delay is no longer neutral. It is expensive.

Oluwatobi Ojabello, senior economic analyst at BusinessDay.