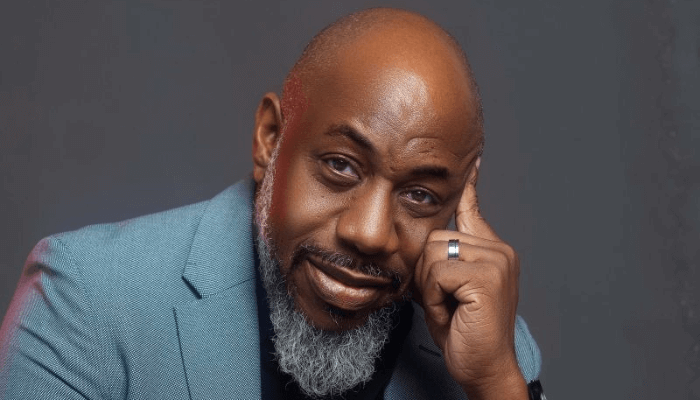

Adetola Ayodele-Oni represents a rare synthesis of legal intelligence and entrepreneurial ambition at a scale few Nigerian professionals attempt. In a business environment where unpredictability often distorts even the strongest commercial ideas, she has built a career on a simple, profound truth: strong local industries are impossible without predictable contracts, enforceable property rights, and credible regulation. Chairperson of the multi-sector Harv Group and managing partner at Karren Walters Attorneys, Adetola has spent her career proving that indigenous enterprise grows fastest when legal strategy sits at its centre. In this conversation with Stephen Onyekwelu, she explores how Nigerian law can shift from compliance to creativity, from procedure to nation-building – and why the country’s economic future may depend on lawyers who choose to become builders. Excerpts

You have successfully bridged two demanding worlds – top-tier legal practice and multi-sector entrepreneurship. At what point did you realise that law could be more than a profession for you, but a platform for building Nigerian-owned institutions?

I realised quite early in my practice that the law, powerful as it is, was never meant to be confined to courtrooms and contracts alone. It is an engine for structuring economies, protecting innovation, transferring wealth, and designing institutions. The turning point came when I began to advise founders, scale businesses, structure investments, rescue distressed companies, and protect intellectual property. I saw, in real time, how legal strategy could determine whether Nigerian ideas merely survived – or truly scaled.

At that moment, law stopped being just a profession for me and became a platform. A platform for building Nigerian-owned institutions that can compete globally, employ our people, produce value locally, and retain wealth within our economy. I understood that if lawyers remain only technicians, we surrender the seat of influence to others. But if we become institution builders, policy shapers, and entrepreneurs ourselves, we help architect the very systems our nation depends on.

Today, every venture I enter, whether in finance, energy, real estate, technology, or education, is guided by that same conviction: that legal intelligence must sit at the centre of Nigerian enterprise. For me, entrepreneurship is not a departure from the law; it is the highest expression of what law is meant to enable, ownership, sustainability, and generational impact.

Go Local conversations often focus on manufacturing, logistics, and finance – but rarely on the law. From your experience, how critical is indigenous legal innovation to building strong local industries, and where has Nigeria fallen short in using law as an economic development tool?

Indigenous legal innovation is one of Nigeria’s most underutilised tools for economic development. From my journey as both a lawyer and an entrepreneur, I’ve seen firsthand that law is not just about compliance, it is economic infrastructure. Strong local industries are built on predictable contracts, enforceable property rights, credible regulation, and fast dispute resolution. When these are weak, capital hesitates and innovation slows.

Nigeria has not fallen short in the volume of its laws, but in how strategically they are used. Our legal system is still largely reactive, responding after industries have already evolved. Enforcement remains slow and inconsistent, and law is often treated as a procedural requirement rather than a deliberate tool for industrial growth.

As an entrepreneur, I’ve felt this gap directly, structuring contracts in uncertain regulatory spaces, navigating weak enforcement, and having to build private compliance systems to protect investments. Yet I’ve also seen what is possible when law works: access to finance improves, partnerships scale faster, and businesses gain confidence to expand.

The future for Nigeria lies in locally intelligent law, regulation that reflects our realities, supports innovation, and actively drives enterprise. When the law becomes a growth partner instead of a bottleneck, Nigerian industries will not just survive, they will compete globally.

Read also: Nigeria’s local industries push to export made-in-Nigeria goods

The Harv Group operates in gas, logistics, financial services, and mobility – industries usually dominated by capital-heavy, often foreign-backed players. What legal strategies and structures have been most decisive in helping your businesses compete and scale locally?

Competing and scaling in capital-intensive sectors like gas, logistics, financial services, and mobility, especially against foreign-backed players, requires much more than operational excellence. For us at the Harv Group, law has been a strategic weapon, not a back-office function. Three legal strategies have been most decisive:

First, we built our businesses on locally optimised corporate and regulatory structures. Rather than copy foreign models wholesale, each subsidiary is structured to align tightly with Nigerian regulatory realities, whether sector-specific licensing, tax efficiency, or compliance layering. This has allowed us to move faster, reduce friction with regulators, and operate with certainty even in volatile policy environments.

Second, we’ve used contract design as a growth and risk-control tool. From supply and haulage agreements to fintech partnerships and financing arrangements, our contracts are deliberately engineered to protect cash flow, allocate risk realistically, and preserve control at the local level. This is critical when competing with better-funded international players, we may not always outspend them, but we out-structure risk.

Third, we prioritised Nigerian ownership, asset protection, and bankability. Proper security documentation, enforceable guarantees, and clean corporate governance have made our businesses credible to local lenders, investors, and strategic partners. That credibility unlocks funding, and funding unlocks scale.

Ultimately, the decisive advantage has been treating legal strategy as a growth strategy. It’s how we protect value, attract capital, manage regulatory risk, and ensure that Nigerian-owned companies don’t just survive, but compete confidently and sustainably in industries long dominated by foreign capital.

Many young women see law strictly as a courtroom or corporate career. What does legal entrepreneurship mean to you, and what mindset shift must Nigerian women lawyers embrace to move from employees of systems to builders of local economic engines?

To me, legal entrepreneurship is the deliberate use of legal knowledge not just to service the economy, but to create, structure, protect, and scale Nigerian-owned businesses. It is the shift from seeing law as a job description to seeing it as infrastructure for wealth creation, innovation, and nation-building.

For a long time, many of us were trained to aim for the courtroom or the corporate ladder. Both are honourable paths, but they are still within systems built by others. Legal entrepreneurship is choosing to build the systems ourselves: firms, platforms, products, holding companies, technology, logistics, energy ventures, and financial structures that employ people, solve local problems, and retain value in Nigeria.

The most important mindset shift Nigerian women lawyers must embrace is this:

from security to ownership, from perfection to execution, and from permission to initiative.

First, we must stop seeing salary as the highest form of success. Ownership is. Equity is. Control of assets is. The law gives us a unique advantage, we understand risk, regulation, contracts, and structures. That means we are already wired for entrepreneurship; we just need the courage to deploy that knowledge beyond client files.

Second, we must release the fear of getting it “perfect” before starting. Many brilliant women remain stuck in analysis while others with less skill take the market. Businesses are not built by flawless planning; they are built by decisive movement, learning through motion, and constant restructuring, all things lawyers are trained to do.

Third, we must stop waiting to be chosen. Too many women wait for partnerships, promotions, or validation. Legal entrepreneurs self-authorise. You identify a gap, build a structure around it, raise capital or bootstrap, and scale – legally, ethically, and strategically.

Finally, young women must understand this: You can be a world-class lawyer and a serious business owner at the same time. The future of Nigerian wealth will not be built by employees alone, it will be built by women who turn their legal minds into economic engines, who design companies as deliberately as they draft contracts, and who see the law not just as a profession, but as a platform for power, policy, and prosperity. That is legal entrepreneurship to me.

Nigeria imports not just goods, but also legal templates, regulatory models, and deal structures. What would it take to deliberately build a powerful local law talent pool that drives innovation in local content, energy transition, logistics, and MSME growth?

To build a powerful local law talent pool, Nigeria must stop treating law as a borrowed operating system and start treating it as economic infrastructure. For too long, we’ve imported not just goods, but deal templates, regulatory models, and transactional thinking that were never designed for our realities. The result is compliance without creativity.

What we need is a generation of lawyers trained around Nigerian economic problems, energy transition, logistics, MSME finance, climate projects, not just foreign case law. Lawyers must move from being document processors to deal architects who can structure risk, unlock capital, and convert local enterprise into bankable ventures.

We also need far deeper collaboration between regulators, industry, and indigenous firms, so lawyers understand operations, not just regulations. Just as importantly, Nigeria must invest in legal innovation, labs, sandboxes, and standard-setting driven by Nigerian lawyers. And as a woman building in both law and business, I believe strongly that women must be raised as builders of institutions, not support layers. A country cannot build indigenous economic power while half its legal intelligence is sidelined.

Ultimately, legal sovereignty is built when Nigerian lawyers stop waiting for foreign precedents and start creating frameworks others adopt. That is when law becomes a true engine of national growth.

Beyond business, you are deeply invested in family welfare, education, and social stability. How has your work in family law and social advocacy shaped the way you design businesses that are not just profitable, but socially stabilising?

For me, family law and social advocacy stripped business down to its true purpose: stability. When you sit with families in crisis – custody battles, inheritance disputes, domestic violence, broken support systems – you see clearly how fragile the social fabric is, and how easily economic pressure can shatter it. That experience permanently re-ordered how I build businesses.

Every company I design now is intentional about protecting dignity, reducing pressure on families, and creating predictable income pathways. I think about working parents, women returning to work after trauma, young people without safety nets, and households one emergency away from collapse. That lens affects everything, from employment policies and payment structures to governance, conflict-resolution systems, and long-term financial planning.

Social advocacy also taught me that profit without stability is short-lived. A business that extracts but doesn’t stabilise eventually feeds on its own community. So I deliberately build enterprises that absorb shocks rather than create them, businesses that train, formalise, insure, mentor, and decentralise opportunity.

In essence, family law taught me that strong societies are built the same way strong families are built: with structure, fairness, accountability, and care. That philosophy now sits at the heart of how I practice law and how I build companies, not just to scale revenue, but to quietly hold society together where systems often fail.

With your interest in Nigerian politics and policy direction, what must change, urgently, at the policy and regulatory level for Go Local to move from a slogan to a sustained national economic strategy?

For Go Local to become a serious national economic strategy – and not just a patriotic slogan – Nigeria must urgently move from policy promises to policy discipline. From my seat as a lawyer and serial entrepreneur operating inside heavily regulated sectors, five reforms are non-negotiable.

First, we need regulatory certainty, not regulatory chaos. Businesses cannot scale when rules change mid-investment or when multiple agencies regulate the same activity differently. For local industries to thrive in Nigeria, policies – especially in energy, logistics, manufacturing, and technology – must be predictable, stable, and enforceable over the long term.

Second, local content must shift from participation to ownership. True Go Local is not Nigerians acting as subcontractors at the bottom of the chain. It is Nigerians owning refineries, gas processing plants, payment infrastructure, logistics platforms, and data systems. That transition requires tax incentives, credit guarantees, and long-term capital structures deliberately designed for indigenous control.

Third, micro small and medium enterprises (MSME) finance must be rebuilt from the ground up. At current interest rates and collateral demands, local production is structurally discouraged. Policy must force a reorientation of finance away from short-term trading and consumer credit toward long-term productive enterprise in energy transition, manufacturing, transport, and agro-processing.

Fourth, enforcement – not new legislation – is the real reform now. Nigeria is not short of good laws. The weakness is inconsistent, selective, and manual enforcement. When regulation becomes transparent, digitised, and corruption-resistant, local capital will unlock at scale.

Finally, the government must become a buyer, not just a regulator. No country industrialises without the state acting as a first customer. Public institutions must consistently procure Nigerian-made solutions in power, mobility, construction, software, healthcare, and security, at commercial scale, not pilot level.

In the end, Go Local will only succeed when policy stops protecting systems and starts protecting Nigerian producers. With stable regulation, accessible capital, clean enforcement, and deliberate government procurement, Go Local stops being a slogan, and becomes a national economic engine.