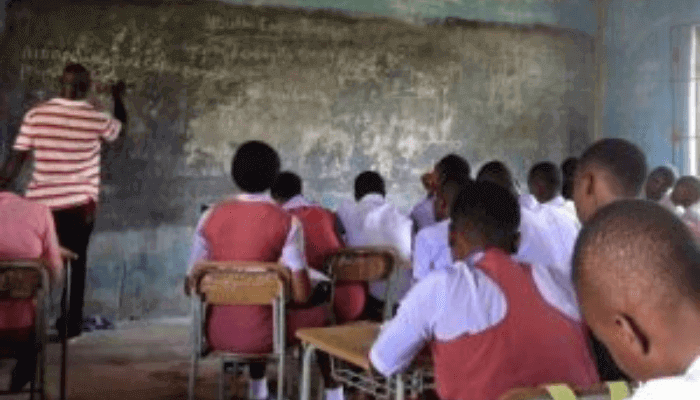

When seven-year-old Uwakwe Iroha sits in his crowded classroom at Amaba Central School, he can confidently recite the alphabet in his native language. Yet, he struggles to read a simple sentence in English.

For Joseph Abe, a father of three, watching his 10-year-old son David remain stuck below grade-level reading raises deeper concerns. Where exactly is the system failing?

Their experiences mirror a national crisis: millions of Nigerian children show up to learn each day, but far too many leave without foundational literacy and numeracy skills.

In response to the worsening learning outcomes, education, Tunji Alausa, education minister, announced the scrapping of the mother-tongue policy and reinstated English as the primary language of instruction across all levels.

Read also:┬аUNICEF enrols 33,532 out-of-school children on digital learning in Borno

тАЬWe have seen a mass failure rate in WAEC, NECO and JAMB in certain geopolitical zones of the country, and those are the ones that adopted this mother tongue in an oversubscribed manner,тАЭ Alausa said, noting that English will now be the medium of instruction from pre-primary through tertiary education.

Why mother tongue matters for learning outcomes

Beyond the Federal GovernmentтАЩs rhetoric, experts believe there are more to studentsтАЩ poor performance at external examinations than the mother tongue.

Gift Osikoya, a teacher, emphasised that mother tongue matters for learning outcomes because of cognitive foundations and comprehension, improved participation and engagement, among others.

тАЬWhen children learn in their first language, they generally understand concepts more deeply because they do not have to wrestle with both new content and a foreign language.

тАЬResearch suggests that using mother tongue encourages greater participation in class, because students feel more confident expressing themselves,тАЭ she said.

Nubi Achebo, director of Academic Planning at Nigerian University of Technology and Management (NUTM), said, among other things, motherтАСtongue matters for learning, as it helps students to comprehend new concepts faster, having got the vocabulary and mental structures to map onto the second language.

Speaking on the mass failure among students, Achebo emphasised that the Federal GovernmentтАЩs recent reversal points to a few intertwined issues, such as inconsistent implementation, exam language mismatch, and socioтАСeconomic factors, among others.

тАЬMany schools that were supposed to use mother tongue as the medium of instruction lacked trained teachers, appropriate, and monitoring. The result was a halfтАСbaked approach where pupils were taught in a language they barely understood, leading to poor subject mastery.

Read also:┬аExpert urges integration of local, international languages in early education

тАЬExternal exams are still set entirely in English. When children are taught core subjects in their mother tongue but are tested in English, the gap can appear as тАШfailure,тАЩ even if the learners have grasped the concepts,тАЭ he said.

He noted that making English the compulsory medium of instruction from primaryтАпone upward does address the examтАСlanguage mismatch, but it also risks widening the achievement gap for children who enter school with limited English exposure.

The policy, he said, may improve shortтАСterm test scores, yet it could erode the cognitive advantages that the mother tongue provides.

Cultural identity and equity

Learning in oneтАЩs indigenous language affirms studentsтАЩ cultural identity and helps preserve linguistic heritage.

According to UNESCO, multilingual education fosters inclusive societies, where the rights are guaranteed, and it is also a pillar for preserving non-dominant, minority, and indigenous languages.

Similarly, Andres Morales, the UNESCO representative in Mexico, said that when a language disappears, a world-view, a way of seeing life and identity also disappear.

Relationship between mother tongue use and exam failures

Lagos State, earlier in the year, announced a 56.29% failure in the 2024 WASSCE, making a mockery of the N1.57 billion the state government claimed it spent on enrolling students for the examination.

Generally, the 2024 WASSCE recorded a failure rate of 54.3%, while in 2023, the failure rate was over 52%.

However, Osikoya insisted that beyond mother tongue, there are other factors responsible for the failure rate, such as mismatch between instruction language and exam language, and assessment design bias, among others.

тАЬIf children are taught in their mother tongue in early grades but then examined in English (or another language), there may be a transition problem.

тАЬLearning concepts in mother tongue does not automatically guarantee fluency in English for exam-taking. If the switch is abrupt or without sufficient scaffolded support, students may struggle in the exam language,тАЭ she stated.

Read also:┬аHow human skills, knowledge can impact future of learning in Nigeria тАУ Report

Teacher training: the real missing link

Both experts agree that sustained investment in teacher training тАУ not a blanket policy reversal тАУ is the real solution.

тАЬThe Government should train teachers in bilingual methods and develop quality textbooks and materials in local languages,тАЭ Osikoya said. тАЬA phased, well-resourced bilingual system would serve learners far better than abandoning mother tongue altogether.тАЭ

Achebo added that the biggest challenge is teacher readiness. тАЬMost teachers are only comfortable teaching in English. Delivering core subjects in local languages requires massive, long-term trainingтАФa costly but necessary undertaking.тАЭ